Amidst cynicism about the press and democracy, journalism educators and researchers need to use their roles in the classroom and in public life to help push the case for media freedom. This requires us not only to re-energise time-tested principles of public interest journalism, but also to question some long-held assumptions and to re-set our norms and practices around universal human rights. This is the edited text of my opening keynote speech at the 2023 Journalism Education and Research Association of Australia annual conference in Sydney in December.

PDF available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4663244 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4663244

This is not going to be a review of the state of press freedom around the world, for which there ample reports you could consult. Instead, I am going to revisit some first principles. The idea of press freedom is often misunderstood. Clarifying the concept can help us defend it and advocate for it more effectively.

I’ll do this by asking a series of simple questions: Whom does media freedom belong to? Why is it important? What’s in its way? And, where in the world should media freedom apply?

Whom is it for?

First, to whom does press freedom belong? Whom is it for? Too often, media organisations talk as if press freedom is a right that’s primarily for the press — that is, for themselves. But it’s worth recalling that the first national constitution to enshrine freedom of the press, that of the United States, did so when media organisations as we now understand them didn’t exist. The press back then amounted to lone pamphleteers, the equivalent of today’s bloggers. So, press freedom was not designed to protect any particular institutional form but a certain kind of practice — acts of journalism.

In her 2022 report, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on freedom of expression made this point, that it’s really acts of journalism that we should be trying to protect and promote. I understand these acts as a public service: journalism is the reporting and analysis of current events to help people makes sense of change and take part in public life.

Large media organisations try to persuade us that they are central to this collective enterprise. It’s true that democracies would be significantly impoverished if they allowed big commercial media to fade away without a Plan B in sight. But it’s not true that there aren’t viable Plans B and C. Most liberal democracies have public service media that serve as vital correctives to the commercial business model. And one of the most exciting developments of the past decade has been the proliferation of small, independent, mostly not-for-profit, public-interest journalism ventures.

So although news media in capitalist societies mostly take the form of privately-owned, profit-seeking organisations, we shouldn’t be too quick to conclude that this is the form we most need to protect in the name of press freedom. We shouldn’t assume that these firms are, by definition, the most hospitable hosts for acts of journalism.

Nor should we slip into the ownership fallacy, that press freedom belongs to the owners of the press (of whatever type). I’ve always preferred the formulation offered by John Hartley here at the University of Sydney, that journalism is a human right possessed by all. We delegate this job to professionals and specialists of the craft for purely practical reasons — most people just don’t have the time or the training to do all the acts of journalism that need to done. But this delegation of responsibility doesn’t mean the right is no longer the public’s.

Once we appreciate that press freedom belongs to the people, many things fall into place. It means, for example, that the professional ethos of journalists should be public service, and that we should be encouraging organisational forms that minimise conflicts of interest between that public service ethos and commercial or political priorities of owners.

The failure to regulate these conflicts of interest, whether by law or through industry self-regulation is one of the biggest blind spots in the media’s exercise of its democratic freedoms.

Most journalism codes of ethics include sections on conflicts of interest: they deal with compromising situations that media workers may find themselves in. That’s well and good. But such codes should extend to media owners. Hardly any do so. Why shouldn’t owners be subject, at the very least, to transparency requirements so that their involvements in other businesses are a matter of public record? In a tiny number of news organisations, owners and investors have signed agreements promising non-interference in editorial operations. Why shouldn’t this be standard practice? European MPs are pushing for such reforms in the proposed Media Freedom Act, but they are bound to be resisted by media owners.

Graham Murdock of Loughborough University has made the powerful point that we are dealing here with more than just business models, which is the conventional way the profession thinks about these things. He describes the problem as a choice between “moral economies”. We are really choosing between different forms of social relations, and different ways of treating media products and cultural services — as mere commodities to be traded for financial gain, or as gifts, or as public goods.

None of the alternative ways of organising journalism is perfect, but then the perfect is the enemy of the good. Nor need we think of these as either/or solutions. A healthy media system is one with different organisational types, each with strengths that can help compensate for another’s weaknesses. The problem in most countries today is that we have placed too many of our professional eggs in the commercial basket. Our societies would be better off if we invested far more in forms that do not treat journalism as a commodity.

We would think through these options more clearly if we remember who’s actually the rightful owner of press freedom.

Why is media freedom important?

Why it’s important sounds like a question with very obvious answers. I assume that in a liberal democracy like Australia, the value of press freedom is something you don’t have to learn. It’s in the air you breathe. I, on the other hand, have spent my entire career in jurisdictions with few protections against state censorship — Singapore and Hong Kong. I’ve not had the privilege of being a participant observer in a liberal democracy’s love affair with press freedom. It’s more like visiting a museum to see a distant culture, peering at its artefacts through glass, knowing it will probably never be yours.

So, you know better than I that a free press helps us keep an eye on governments and others with the power to affect our lives. You know that a free press also serves the important democratic function of giving voice to public opinion. These ways of thinking about the press place it in the middle of that important vertical connection between state and society.

But democracy is more than about state-society relations. And here is where I think there’s another blind spot, even among born-and-bred citizens of liberal democracies. Freedom of expression is also a process for getting right our horizontal, people-to-people communication. It’s a way to allow different communities to listen to one another even, or especially, across seemingly unbridgeable partisan, ideological, and cultural divides.

Some of the political dysfunctions of today’s liberal democracies and their media are linked to a failure to grasp, internalise, and realise democracy’s potential for managing social diversity. The emphasis on state-society competition makes us treat democracy, together with its associated freedoms, as little more than a struggle to establish and empower the popular will. This can quickly descend into its own tyranny — the tyranny of the majority — and mob rule. In the worst cases, it leads to ethnic cleansing and genocide.

If we instead go back to fundamentals, we would appreciate that democracy requires that majoritarianism — the will of the people established through elections — be balanced with equal rights for minorities. Democracy therefore requires a journalism that is as attuned to equality as it has been to freedom.

Equality doesn’t just mean that minorities must be treated the same as everyone else. It requires special protections for vulnerable groups against hate speech — incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence — because while dominant groups are able to fight speech with speech to protect themselves from identity-based attacks, minorities are relatively powerless in the free marketplace of ideas.

Equality usually also requires special accommodations to ensure that we can hear minority voices in a public square dominated by the majority group’s language, norms, and agendas. Democracy is nothing special and press freedom isn’t worth fighting for if all they do is amp up what were already the loudest voices. Such a moral order would not really be a step up from mob rule. Rather, media freedom is valuable to the extent that it enables everyone to hear the quieter voices in the room.

From this perspective, Australia’s recent attempt to establish an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to Parliament should have been quite uncontroversial. Sure, the Yes campaign had flaws and of course there was an intense disinformation campaign from the No side. But when I look at how modest the Voice proposals were, compared with say the co-governance mechanisms already in place in New Zealand, I can’t help but think that the Referendum outcome resulted from a long-term failure in civic education, both by schools and the media, to explain to the majority of Australians that the democratic freedoms they prize aren’t particularly noble or even civilised if the main beneficiaries of those freedoms don’t keep looking for ways to ensure that the voices of those on the margins are also heard.

Looking at these dynamics across various other democracies, I don’t think the Right is exclusively to blame if there’s now a disconnect between free speech and equality. Segments of the Left — what’s been called the Cultural Left or illiberal progressives — share some of the responsibility. While the Right tells us to pursue speech freedoms without caring about equality, there are those on the Left who pursue equality as if it can be achieved without free speech. The Left has sometimes been too quick to cancel and deplatform, and to punish and drive out hurtful speech.

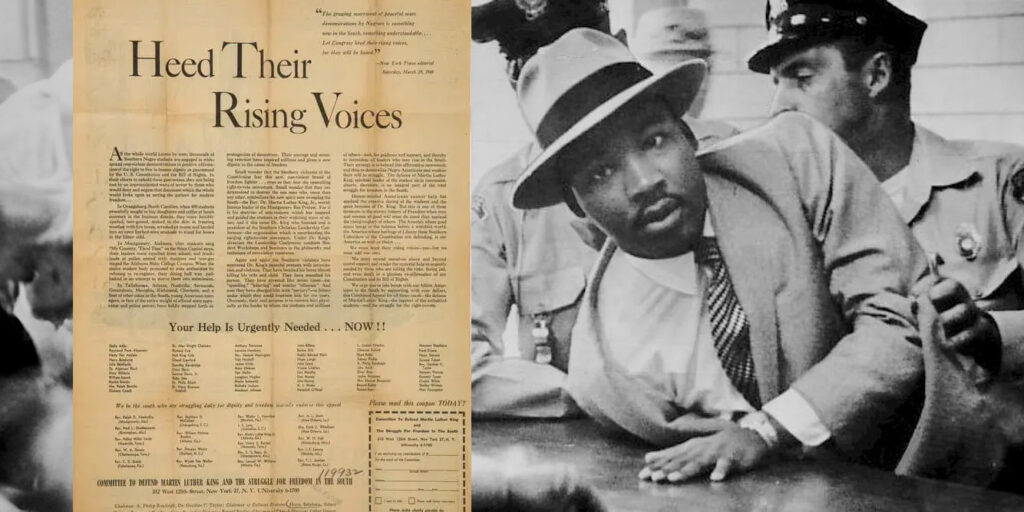

Illiberal progressives’ suspicion that free speech is a threat to racial and social justice is understandable but quite ahistorical. All the quantum leaps in racial and social justice of the past century needed free speech as a springboard. Struggles over colonial rule, women’s suffrage and apartheid were simultaneously struggles for freedom of expression, among other rights.

The Economist had an article a couple of weeks ago speculating that the wave of censorship of pro-Palestinian voices in western democracies, including at universities and media companies, might make progressives once again discover that freedom of expression is their cause too. If we forgot this along the way, it’s because we’ve not fully appreciated that free speech is a prerequisite for constructing more inclusive societies.

What’s in the way?

What’s in the way of media freedom? The principles that I’ve highlighted so far should help us answer this question with greater precision than we tend to. Freedom from government coercion is what we usually mean when we talk about press freedom, and this is still a major, if not the major, challenge facing journalists around the world. Because it’s so obvious, it need not detain us further.

For a more holistic picture of the conditions required for journalism to fulfil its public role, we can refer to UNESCO’s various documents and reports. They are embedded in international human rights principles rather than any one country’s constitutional tradition or political system, making them globally resonant.

UNESCO says the press must be free from government restrictions that are not in line with human rights principles. But journalists should also enjoy editorial independence, including from their own employers, since, as we’ve established, press freedom was never intended as licence for owners to grow in wealth and power at the expense of the public interest. And since we want media to help us construct more inclusive societies, media ecosystems should be plural, sustaining multiple outlets to ensure that all relevant voices can be heard. This set of three conditions for a healthy media system — freedom, independence, pluralism — should sensitise us to the range of possible obstacles that we should be paying attention to.

Even if media are mostly free from government control, they may lack independence if the majority of outlets are owned by businessmen who do not allow their media to compromise their various other business interests by, for example, investigating these firms’ misconduct or annoying their political patrons. The system may also be insufficiently plural due to the forces of industry concentration.

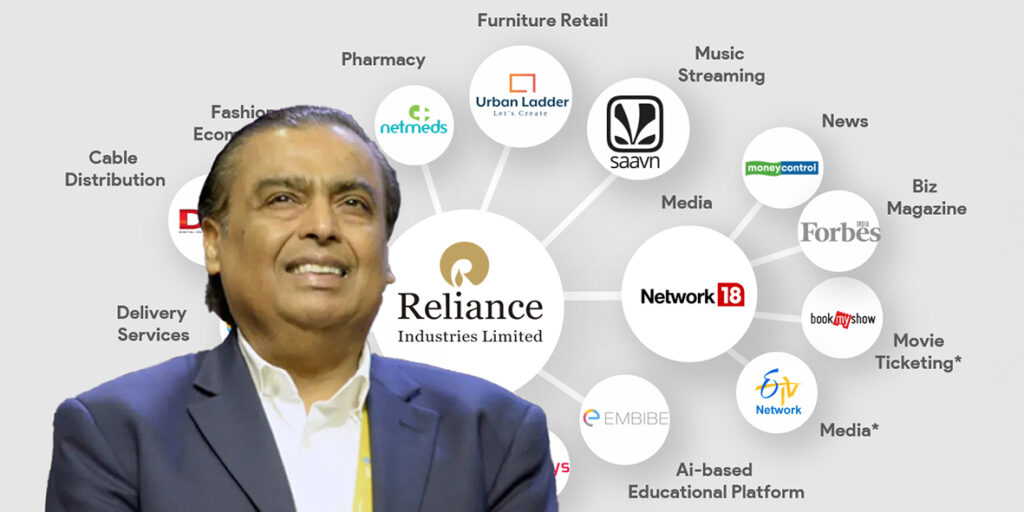

Western opinion columnists who speak up for press freedom in other countries tend to pay more attention to government censorship than threats to independence and pluralism. This may be because of a lack of awareness, but it could also be because it’s hard to shine a spotlight on independence and pluralism elsewhere without drawing attention to the same problems in one’s own news organisation and media system. It would be the pot calling the kettle black if, for example, the Murdoch empire’s newspapers and news channels railed against how Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani have used their Indian media industry megaphones to support right-wing politicians. Far safer to stand up for global press freedom by, say, decrying government clampdowns on media in Hong Kong. There is a big gap between democracies and non-democracies when comparing government repression, but owner interference and industry concentration are common to most regime types.

Partly because they are less likely to draw attention, control-minded states have increasingly applied economic carrots and sticks, instead of more visible violence or media laws. They have found ways to co-opt private sector owners so they don’t need to nationalise the press. Researchers increasingly talk about “media capture” — interventions, often gradual and not sensational, through which the state transforms the inner workings of commercial news organisations, turning them from watchdogs to lapdogs. Governments sometimes do this by mounting crippling tax probes against the owners, who finally give up and sell the outlet to a crony capitalist.

Media capture also targets public service media. Governments pack their boards with loyalists and pass top editorial positions from professional journalists to civil servants. The latter is exactly what has happened to Hong Kong’s public broadcaster RTHK, which operates five television channels and eight radio channels as well as websites in Chinese and English. It used to operate quite independently of the government, inspired by the likes of the BBC. That editorial independence has been severely compromised. It’s still not like China’s CCTV, a mere mouthpiece of the state, but it has been forced to behave more like a government station. You have probably heard of the dramatic death of the city’s popular newspaper Apple Daily and the arrest of its founder Jimmy Lai. I wouldn’t be surprised, though, if RTHK doesn’t ring a bell. Media capture tends to happen below the radar, even though its effects can be as serious or even more so than the arrests and bans that make international news.

One quibble I have with media freedom and human rights advocacy groups is that they have yet to catch up with these trends. If you go to their websites or sign up for their newsletters, you will see that their alerts are almost entirely about coercive attacks on media workers, banning of media outlets, and so on. They are less attentive to long-drawn administrative, legal and financial manipulations that states use to bring media gradually under their control.

Sometimes, media capture is so slick that even the journalists affected don’t complain. That’s what’s happened in my own country, Singapore. When I was working as a journalist at the Straits Times in the 1990s, it and its sister newspapers had already been captured via a 1974 law that allowed the government to stack the board of directors with establishment types, and thus control the appointment of top editors. Without needing to take over ownership, the government made sure that its power would never be challenged the press.

In 2021, the Straits Times’ parent group, Singapore Press Holdings, gave up trying to make enough money to satisfy its shareholders. SPH was converted into a not-for-profit trust, largely dependent on government funding. This makes Singapore probably the only advanced industrial country outside of the communist world that has zero commercial daily newspapers, and where all newsrooms large enough to cover domestic news on a daily basis are state-funded. Interestingly, employees seemed to welcome the changes, since the injection of state funds allowed bigger salaries and a hiring spree.

If even journalists aren’t complaining, media capture might seem like a victimless crime. Until we recall our first W: to whom does media freedom belong? Not journalists but the public — which is certainly a victim when the independence of their news outlets evaporates.

Media capture isn’t the only tool of modern authoritarians. Another sophisticated strategy is distraction, or what some call epistemic flooding. Thanks to chronic attention scarcity, governments and other powerful groups don’t necessarily need to remove critical content from the public sphere. They just have to make it less likely to be found and lingered on. And they can do this by flooding platforms with irrelevant stuff or material that creates doubt and sows confusion.

Where is media freedom relevant?

My final question deals with the universality of press freedom as a value. It used to be assumed that the benefits of press freedom, like democracy, would be self-evident to everyone everywhere. But even in democracies, it turns out that journalists have a hard time persuading their own publics that their society would be better off with a freer press. To say that it is “very important that the media can report the news without state/government censorship in your country” sounds like a motherhood statement. Who would possibly disagree? Well, between one-fifth and one-third of people in western democracies, that’s who, according to Pew Research Center surveys in 2019. In Australia, just 69% said it was “very important”. Indians are fond of saying they are the world’s largest democracy, but that pride — or more correctly delusion, since India is no longer classed as a democracy — doesn’t make them strong supporters of the press. Only 37% said a free press was very important.

We used to think that such responses were entirely the media’s own fault. Popular, low-brow outlets were too careless with their freedoms, while high-quality media were so in love with the sounds of their own voices and being part of elite conversations that they neglected to serve or relate to ordinary citizens. Such flaws didn’t just hurt their own organisations’ credibility. They also caused collateral damage to the legitimacy of the media as a whole, including the journalists who, by any measure, are actually committed to public service, sometimes at great risk and with little reward.

So news media do bear much of the responsibility for people’s low trust in the profession and their consequent lack of support for media freedom. But it is no longer the case that journalists are their own worst enemies. That crown now goes to anti-media populism — a new term has entered the political science lexicon. Populist politicians have found it useful to persuade citizens that the press is part of the corrupt elite, along with universities, experts, the courts and centrist parties. We know that these are bad-faith, self-serving attacks, since the main targets of politicians’ #fakenews allegations are not the least professional media outlets but the most. It’s well-run public-interest media that tend to take their watchdog roles most seriously and thus make themselves targets for unscrupulous politicians.

The Pew surveys I mentioned earlier show a clear relationship between populism and anti-press attitudes. People with populist views are defined in that study as respondents who have given up on elected officials and say that ordinary people can solve their countries’ problems better than their elected representatives. The survey found that people with populist views were less likely to see news media as very important for society to function compared with respondents with non-populist views. The difference was as much as 20 percentage points in many democracies. This seems quite irrational. If people don’t trust their elected leaders shouldn’t they want more checks and balances, including a strong press? Clearly, populist disinformation has hit home, persuading supporters that the news media belong in the same basket as mainstream politicians and other democratic institutions, all part of a corrupt structure in need of a strongman-saviour.

A dramatic case of anti-media populism is the hate directed at the founder of Rappler in the Philippines, Maria Ressa, whose Nobel Peace Prize award two years ago — making her the first Filipino Nobel Laureate in any category — only intensified the vicious vilification she received from her countrymen, led by the authoritarian populist president Rodrigo Duterte.

You would think that the victims of anti-media populism can at least count on the support of fellow journalists. Sadly, though, there are usually sections of the media that serve enthusiastically as cheerleaders when politicians attack liberal and independent media. Their motivations are mixed: in highly polarised societies, there are media that have decided to line up with ideological allies and against professional solidarity. But there’s also a self-serving commercial incentive to attack competitors — think of Murdoch media’s decades-old campaign to undermine support for public service broadcasters.

Whatever their motives, these are media that clearly haven’t internalised liberal democracy 101 — that one can disagree totally with what others say but should defend to the death their right to say it. No, these illiberal media want free speech for themselves, and to use that speech to deny others theirs.

When such fundamental liberal values are trashed by opinion leaders in politics and media, it should be no surprise to see the normative infrastructure for civil liberties erode, such that even publics in liberal democracies have a low commitment to media freedom.

As for closed autocracies like China and electoral autocracies like Singapore, there is no strong homegrown liberal tradition to erode. Those of us pushing for more press freedom have no choice but to plant our flag in global human rights norms. This unfortunately opens us to nationalist attack. People in power and their supporters claim that media freedom is a western imposition, and those of us pushing for it are western lackeys, ignoring the fact that most of these non-western countries have signed the United Nations documents enshrining such rights.

Anti-press propaganda in authoritarian states highlight the worst examples of western media to demonstrate the obvious fact that press freedom does not guarantee press quality. The critiques also point out myriad western media’s hypocrisies and double standards when covering non-western societies. There’s now a geopolitical dimesion to these debates. Both Russia and China have invested in cross-border propaganda in the service of what the Chinese call discourse power. Tired of being on the defensive on subjects like press freedom, they now feed the global debate with talking points that cast doubt on such principles.

Such rhetoric often falls on fertile ground. I don’t have the data for this, but my strong impression is that a high proportion of Asians across different cultures and political systems instinctively believe western media are propaganda vehicles for the west and are biased against the global south whenever their interests diverge. That generalisation conceals some important counter-points. As I point out to my students, western media are not monolithic. Yes, there are outlets that haven’t shaken off their orientalist worldviews, but there are also highly cosmopolitan ones that are more respectful of global diversity than many global south news organisations (Asian media, for example, can be quite racist against Africans). Furthermore, practically all the accurate criticisms global south citizens raise against western democracies originate from the west itself.

Consider for example last week’s death of Henry Kissinger. My country’s foreign minister eulogised him as the “pre-eminent statesman of our time” (which was rather insensitive to neighbouring countries that were victims of his amoral Cold War calculations). Commentators elsewhere in the global south were more scathing about his legacy. But perhaps the most devastating critique came from an American journalist, Nick Turse, writing in an American media outlet, The Intercept. He produced the most conclusive and devastating investigative report about Kissinger this year (timed for his 100th birthday), demonstrating his direct responsibility for the murder of tens of thousands of Cambodian civilians.

This is just one example of western media’s hard-hitting investigative journalism into the global misconduct of their own governments and corporations. This may be happening only on the margins of western journalism, but at least those margins are wide, buzzing with activity, and making an impact. In contrast, if you are looking for revelatory journalism about China’s expansion into the South China Sea or the dubious practices of China Inc in the Global South, the last place you’d find it is in Chinese media, whether mainstream or in its almost non-existent margins.

Having said all that, there is no doubt that western media generate more than enough grist for the anti-western mill through its pompous condescension and unfounded self-righteousness. Some of this is due to cultural ignorance and unconscious biases, like making sweeping generalisations about other countries. It’s as if they think our non-western societies are less complex than their own. Perhaps this can be corrected through more education and exposure.

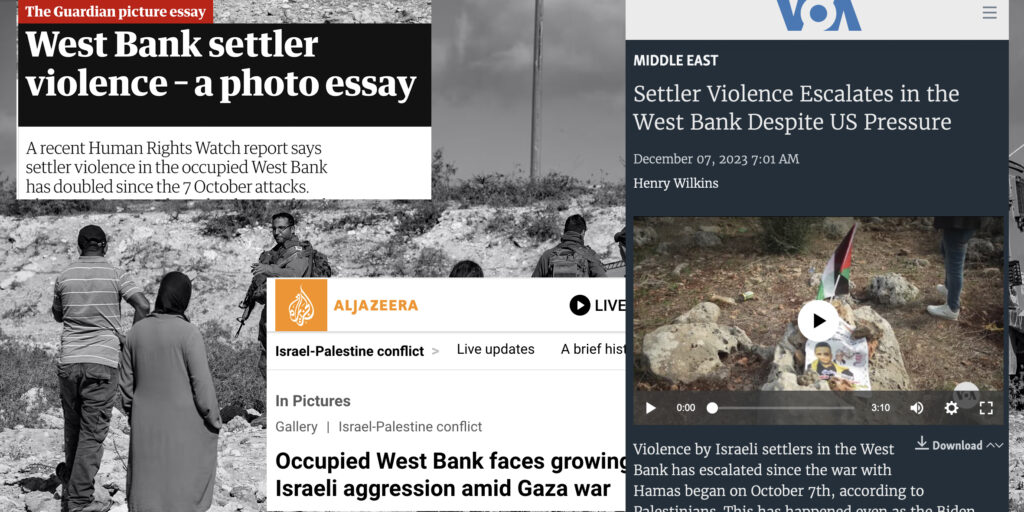

But there also other flaws in western media reporting that can only be the result of conscious, deliberate decisions. Mainstream US media avoid using the term “occupied territory” in reference to the West Bank, or calling Jewish settlements there “illegal”. These words tend to appear in their articles only in quotes from a newsmaker or interviewee, as if these objective descriptions are just someone else’s opinion. The pattern can’t be accidental, because it’s so consistent, and in such a high-profile context. The Associated Press is honest enough to say in its style guide that the West Bank can be described as occupied territory. It would be interesting to research how often its journalists and news media clients actually use the term compared with, say, the Guardian or Al Jazeera English.

If American media so brazenly go along with a might-is-morality principle when covering Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, that’s their editorial prerogative. But they should not be so naïve as to think there’s no cost to their moral standing globally; that intelligent readers around the world won’t roll their eyes when columnists in these same news outlets pontificate about the need to respect international law in Ukraine, for example, or question how China has crushed Hongkongers’ demands for more autonomy.

If you do really want to help sell the values of press freedom to countries that don’t have it, you might want to try more show, less tell. Show the difference that principled, public interest journalism makes to your own societies. Tone down the preaching, which tends to appeal at most to the converted.

I’m only emphasising the culpability of western media in giving press freedom a bad name because I’m here in Australia among western media educators. Media educators in Asia should in the meantime be looking in the mirror and examining our own biases, instead of distracting ourselves and our students by blaming everything on the west. If Asian societies choose to reject the gift that is human rights because we suspect it’s a Trojan Horse for western imperialism, if we can’t talk about press freedom for our own countries without immediately wondering if we are conceding something to the west, it’s not western media that’s to blame. It’s our own colonial hang-ups we have to question.

Democratic models and press freedom

I’ve raised some fundamental questions about press freedom because I think we as journalism educators and researchers need to think harder about the normative foundations of our work. I don’t want to suggest that there are textbook answers that everyone will agree on, even within liberal democracies. Our approach to press freedom depends a lot on the model of democracy we subscribe to. And there are very different models of democracy currently in circulation.

There are those who believe in more elite-led representative democracy, such that the direction of country is left to professional politicians and other big interests to debate over and decide. They fear that too much participation of the masses will only lead to democratic overload and gridlock. If you believe that, then it’s likely you favour big corporate media that mirror the prevailing power structure. You would envisage journalism as a bridge between the elites who run things and the society that should just watch from a distance and occasionally vote.

But there’s another view of democracy that is more hopeful about citizen participation, and wants to widen and deepen democratic deliberation. This translates to a model of the press as radically inclusive, and suspicious of the status quo. It is not only free but also independent and plural. No prizes for guessing that I’m more inclined to this latter approach. Journalism education and research will, I hope, be built on these normative foundations — always questioning who benefits and who’s left out in the way power is currently arranged, and figuring out how might we learn from others’ and our own advances and failures to make things a little better for the societies we serve.