This article was commissioned by the news agency 360info.org for World Press Freedom Day 2022, and can be freely republished under a Creative Commons licence.

Six months after journalists Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov were honoured with the Nobel Peace Prize, little of the celebratory mood remains. Ressa’s Philippines is deep in an election season marred by all the dysfunctions independent media like hers have been trying to combat – industrial-scale disinformation and hate speech, patronage politics dominated by oligarchs and other elites, and the appeal of charismatic personalities over human rights.

Muratov’s Russia, meanwhile, has gone to war against its neighbour and made domestic dissent so dangerous that he has suspended publication of his newspaper Novaya Gazeta even as pro-regime television news churn out war propaganda.

Such ups and downs are emblematic of the global situation since the last World Press Freedom Day. Over the past year, print and digital media have produced plenty of exemplary journalism, but the overall picture has grown even more grim. Take India. Once considered the world’s largest democracy, it was relegated to “electoral autocracy” status. Its independent media still survive, and its citizens are — like in the massive farmer protests — still able to foil the state occasionally. But nothing has been able to reverse India’s descent into orchestrated, systemic majoritarian hate.

This mixed state of affairs is partly due to the fact that press freedom is a multidimensional construct. Behind the deceptive simplicity of press freedom indices and rankings are dozens of scores measuring legal, political, economic and cultural factors ranging from whether journalists are protected from government threats and hate speech, to whether media owners encourage self-censorship, and whether the country’s linguistic diversity is well-represented.

Nor is the relationship between press freedom and democracy one-dimensional. Free and independent media are needed to act as a watchdog on power, and to air public opinion. Less obviously, media have another important democratic role — as enablers of conversations among different groups in society, helping diverse communities to constitute themselves as a public and act collectively for the common good.

Technology-driven change affects each of these media attributes and roles in different ways, which is why there is no simple answer to the question of whether the internet has helped or hurt democracy-enhancing journalism.

Overall, it is fair to say that the digital revolution has helped make media more plural, participatory, and protest-friendly. But its contribution to tolerant, diverse publics appears negligible or even negative. This is contrary to hopes two decades ago that the internet would help form a “digital public sphere” far more democratic and inclusive than pre-digital society.

The 15 minutes of fame that digital media dish out to people previously known as the audience does not necessarily add up to a national, let alone global, conversation that cuts across social and ideological divides.

This is a problem because democracy is a highly demanding way to organise public life, requiring not only the freedom to speak but also a commitment to listen and to respect others’ equal rights even when consensus is elusive. But instead of enlarging common spaces for democratic deliberation, the global trend is towards political polarisation, according to the newly released annual report of the Swedish-based Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project.

It defines political polarisation as a division of society into antagonistic “Us versus Them camps”. Over the past decade, by V-Dem’s count, 40 countries have hit toxic levels of polarisation, characterised among other things by the use of hate speech in major political parties’ rhetoric.

The internet is, of course, not the only driver of polarisation. Economic systems’ failure to sustain hope in existing models of progress have generated resentments and fears. Instead of addressing these underlying problems, politicians find it easier to engage in identity politics, scapegoating foreigners, minorities and democratic institutions for their countries’ ills.

Social media platforms have not helped, to put it mildly. They are designed to group people into smaller networks for more efficient commercial microtargeting, rather than create fora for diverse citizens to meet. Their robots’ bias for virality over verifiability has been a boon for the disinformation industry. Beneficiaries include state sponsors of propaganda and their media allies and other private-sector partners. Public-interest journalists are outnumbered and outgunned.

The result is an internet far removed from the vision for a “global social world … that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth” in the words of John Perry Barlow’s 1996 cyberspace manifesto. It is an internet that does not promote mutual understanding and civil disagreement among people’s different views and values.

Social media companies’ enforcement of their community standards, including Facebook’s Oversight Board, are token moves that distract from the urgent challenge to create a new internet. Elon Musk believes he has solutions for Twitter and is putting his money where his mouth is, but it is unclear if he even understands the problem.

We need a more fundamental overhaul, of the kind envisioned by a group of communication scholars and practitioners in their manifesto to create a Public Service Internet. Released last June and signed by more than 1,200 scholars since, it calls for a public-funded “Internet of the public, by the public, and for the public; an Internet that advances instead of threatens democracy and the public sphere, and an Internet that provides a new and dynamic shared space for connection, exchange and collaboration”.

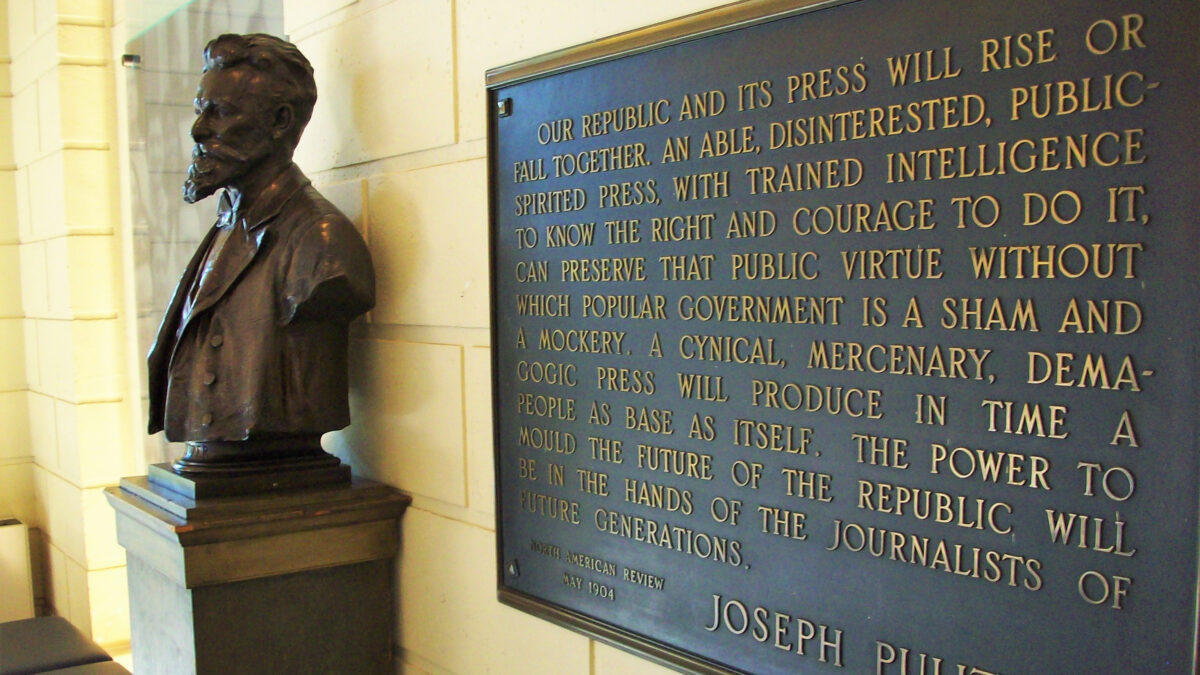

The manifesto also called for investments in public service media. Indeed, it is impossible to conceive of democratic deliberation succeeding in any polity without well-resourced news organisations of sizeable scale that are dedicated to professional norms of public-interest journalism.

A healthy media ecosystem must include national public-funded media independent of the government of the day. These are found in most liberal democracies, but they have been undercut by digital disruption as well as politicians and business people unhappy with these organisations’ autonomy.

In non-democracies, state-funded broadcasters are invariably government-controlled, making them more likely to be part of the problem of political polarisation than the solution.

Within the news industry, most discussions have skirted these questions, focusing instead on sustainable business models for private media organisations in the wake of digital disruptions. Even if these are viable ways to produce substantial, high-quality watchdog journalism, they will lack the reach and scale to serve as a public sphere that can counteract the trends towards political polarisation and identity politics.

The development of a public service internet and public service media need to be on the agenda. The Catch-22, though, is that the highly polarised countries that most urgently need concerted interventions are also the least likely to be able to muster support for the required media reforms.

Cherian George is Professor of Media Studies and Associate Dean for Research, Hong Kong Baptist University School of Communication and Film.