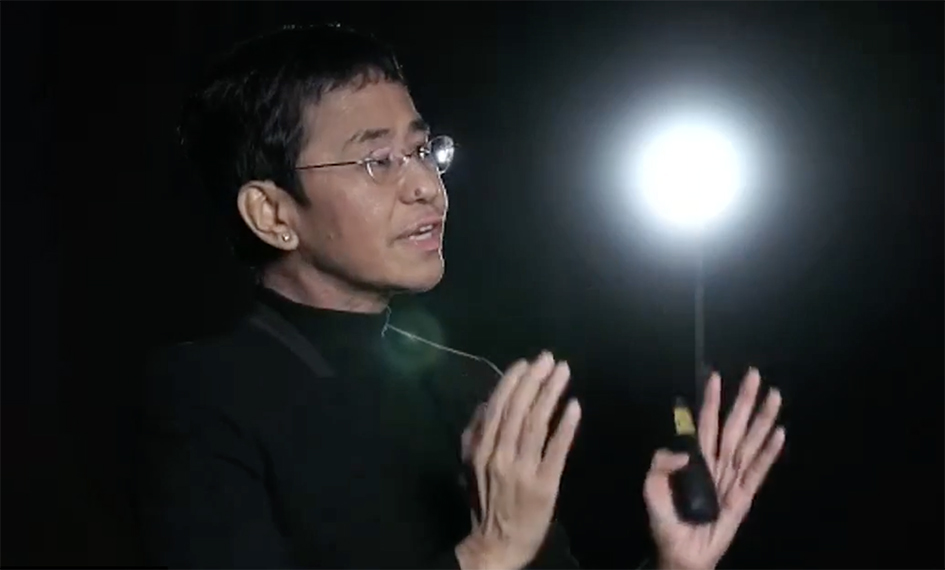

Four days before she received the Nobel Peace Prize, Maria Ressa, founder of Rappler, gave a lecture on Facebook and the Big Lie: Democracy and Disinformation. I was invited to give a response. Here is the text of my prepared remarks.

If you have been following Maria Ressa’s talks over the years, you would know that she’s been engaged in a battle on two fronts, domestically against President Rodrigo Duterte’s unhinged autocratic rule and globally against social media platforms’ unaccountable algorithmic power.

But if you look at the news coverage around her Nobel Prize, it’s clear she’s better known for standing up to the demagogue than for sounding the alarm against digital disinformation. It’s worth probing why that’s the case; why not just Maria’s but also many other warnings have not been taken seriously enough. I think the reasons say something about our vulnerability as individuals and societies to the threats that she has described today.

In her lecture, Maria talked about how her early warnings in 2016 were ignored. The Philippines has been described as Patient Zero afflicted by the online variant of the age old disease of industrial scale disinformation. We should have been paying attention. But it’s only when the epidemic showed up in the United States and Britain that it registered on the global radar. That’s a reminder of our unbalanced world attention order. If a tree falls in a forest and Americans can’t hear it, does it make a sound? Too often, the answer is no.

Similarly, I recall visiting Myanmar back in 2014 and listening to activists pleading for more attention to be given to hate speech on Facebook. They pointed out that the company clearly did not have the capacity to moderate posts in local languages, making its assurances about tackling toxic content quite meaningless. It was clear that Facebook was wilfully blind to the danger it posed to brown lives. It was only in 2018, I think, that the world’s media gave these Myanmar voices serious attention, but still only as a sidebar to the narrative about right-wing hate in the West.

Even now, although online disinformation is high on the global agenda, not all manifestations of this problem are treated as equal. Foreign interference in elections gets lots of press, because that’s what worries the US and Western Europe the most. Other issues get less attention — for example, how states themselves deceive their own people, which is common in Asia; and how public relations and marketing consultancies are implicated in public opinion manipulation, which surfaced in South Africa in the Bell Pottinger scandal and which Filipino scholar Jonathan Corpus Ong and his colleagues have been trying to spotlight.

So, insensitivity to problems felt outside of the Global North is one barrier. Second, most people still don’t understand the technology. Of course we’ve known for a long time that internet intermediaries are basically in the advertising business; we know how the abundant choice that digital media provide enable us to retreat into echo chambers, and to select information, ideas and interlocutors that confirm our biases.

But it’s only recently that we’ve come to realise the extent to which tech companies are able to profile us, and how freely they’ve been selling their services to commercial and political agents who wish to predict and modify our behaviours. These invisible data-driven capabilities are much harder to grasp and are therefore much less salient than, say, policemen firing guns at protesters or a journalist being arrested.

Third, research into the psychology of risk perception tells us that people have greater tolerance for risks that they perceive are under their control (like smoking) than for those that aren’t (like shark attacks). Everything about the internet, from hyperlinks to point-and-click menus and app stores, is designed to give us the semblance of choice and control.

It is of course true that the internet has been a boon for personal empowerment. But the autonomy that we have in cyberspace is not total. Just like our movements in the real world are heavily influenced by the architecture and urban planning of our built environment, what we see and do online is structured by code — code that is now shaped by commercial considerations far more than it was when the world wide web was born some 30 years ago.

Finally, Maria used the term “insidious” to describe this threat, and that’s a very apt term. It’s gradual, subtle, like man-made climate change. It’s the kind of threat that human beings and their media are not very good at processing. We react to larger-than-life dictators who curse and jail their enemies. As for the drip-drip of disinformation, the bit-by-bit erosion of democratic institutions — these go under our radar.

The workings of markets and digital technologies seem almost natural and inevitable, and it takes mental effort to get our heads around how these structures are man-made, manipulative and sometimes malignant.

Especially insidious is the fact that disinformation merchants don’t necessarily need to prove they are right. If you want to depress the vote, disarm civil society activists, and derail progressive reforms, it is often enough to sell negativity, confusion and doubt. All that’s necessary for evil to triumph is for good people to believe nothing.

And this is why I appreciate the message that Maria always ends with it. It’s not about despair; it’s a rallying cry. Against cynical, dehumanising hatemongering, she and her colleagues at Rappler give us something to believe in: journalism that’s truth-seeking, community-building, and democracy-enhancing. Whether we are willing to support such journalism or retreat into apathy is up to us.