Text of a talk at the Asia Journalism Forum organised by the Institute of Policy Studies and supported by Temasek Foundation Connects, Singapore, 17 August 2017.

Experienced journalists know that when interest picks up in some new problem, you’d better pay attention because it may be newsworthy. But we also know that when everyone’s talking about something, we shouldn’t get too caught up in the hype. We need to take a step back to get a wider view.

The “fake news” problem has reached that status, requiring our attention but also some circumspection. It is a real problem, but we should be quite clinical in the way we deal with it, and not go for cures that are worse than the disease. This, I fear, is exactly what will happen if some governments get their way.

In the name of combating fake news, they attack independent journalism. We see this tendency clearly in Donald Trump’s rhetoric, but its effects will be far worse in other countries that, unlike the United States, don’t have strong constitutional protections for press freedom.

This is why UNESCO cautions against the very use of the term “fake news”, pointing out that populist leaders have been using it to whip up hostility against legitimate professional media.

I will still use the term this evening because it is convenient, but I hope the health warning is clear. I’ll also use the term disinformation, which may be more precise.

The fake news problem is part of larger crisis for our profession, which I’d call a crisis of reason.

Journalism as we understand it today as a product of the Age of Enlightenment. Professional journalism—like science—is based on the belief that human society progresses through the freedom to ask questions, gather facts, build and share knowledge, and then ask questions again in an endless cycle. Journalism’s core principles and practices are built on that faith. We treat facts seriously because we believe people’s decisions should be guided by evidence, and we fight for freedom from censorship because we think that it’s through open competition that better ideas will reveal themselves.

But there are growing doubts about the power of reason. Last year’s events in the Western world have forced us to re-evaluate our Enlightenment assumptions.

In major contests between truth and falsehood, in Britain’s Brexit referendum and the US Presidential Election, lies and misinformation triumphed. When people were presented with established facts, they simply refused to believe them, preferring to believe what more reasonable minds knew to be untrue. We’re now asking if we live in post-truth world.

We in Asia are familiar with crises of government control, we are certainly getting used to crises of financial survival, but this crisis of reason is in some ways the most devastating because it undermines the very premises of our profession.

If facts don’t count, if reason doesn’t win, then what’s the point of fighting for press freedom or searching for sustainable business models. Maybe we should just give up and move into public relations.

But I hope you agree that such a conclusion is premature, and that we should try to rise to this challenge.

A recent history of disinformation

Fake news has suddenly arrived on the global agenda not because it’s new, but because of him. And him.

The news about Russian fake news isn’t fake news although Trump thinks it is. The Russians have a sophisticated disinformation machinery dating back to Soviet days, which it’s currently using to nudge European neighbours closer to Moscow’s sphere of influence and away from the EU and NATO. But the focus on Russia’s role in Western politics, can distort our perceptions of where the most serious disinformation threats come from. Here are four of what I’d consider much more serious.

1. Health myths: smoking is OK

First, the campaign to block tobacco regulation.

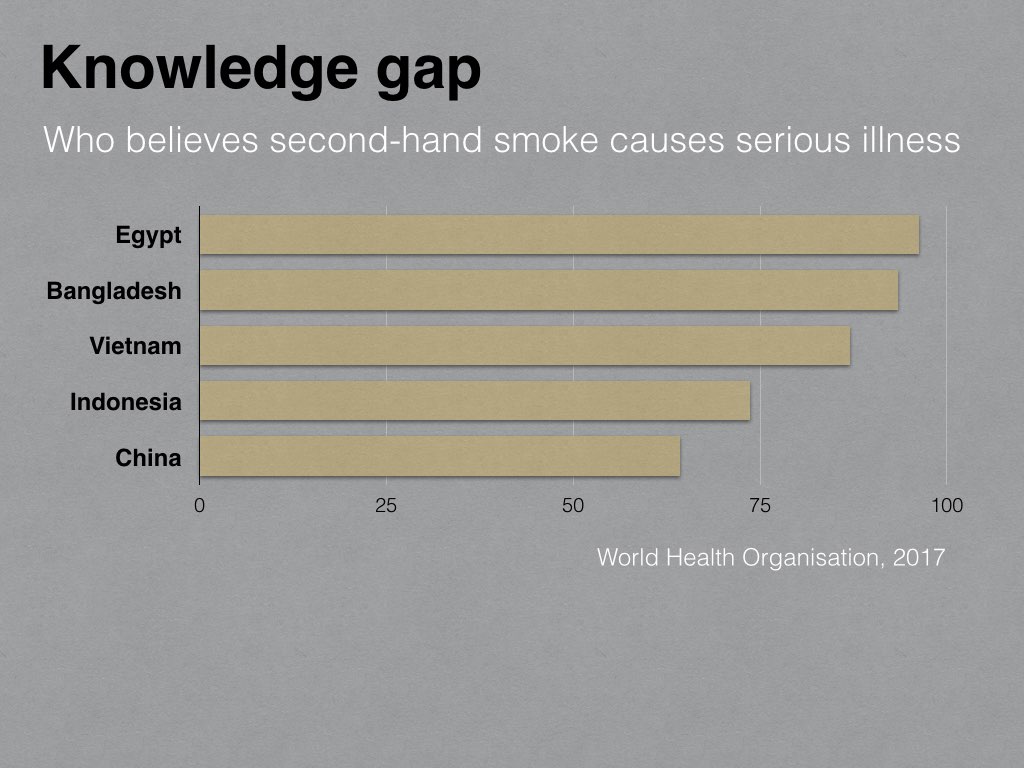

We know that for decades, Big Tobacco worked hard to suppress scientific evidence of the health risks of smoking. They’ve almost lost the battle in the West, but they are making up for it in Asia. Their tactics include falsely promoting filtered or mild cigarettes as less hazardous. They’ve also been funding research aimed at clouding public awareness about the health risks of second hand smoke exposure.

In the key markets of Indonesia and China, only 60–70% believe second hand smoke causes illness.

How serious is Big Tobacco’s disinformation campaign?

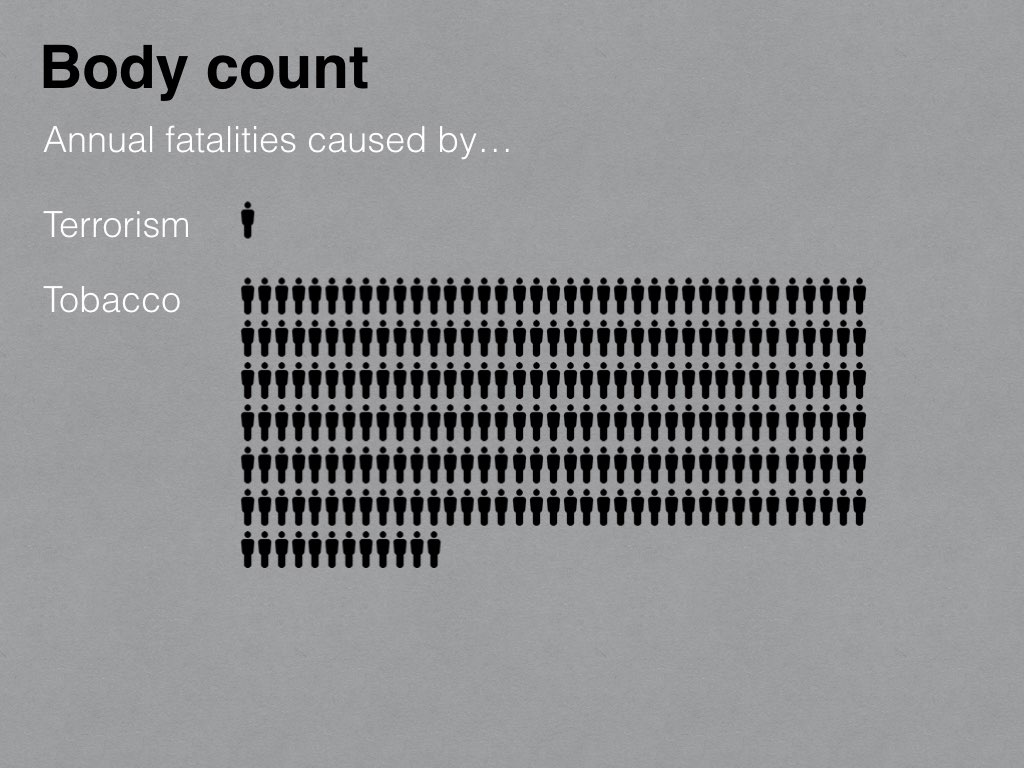

Note that that there were around 25,600 deaths in terrorist attacks in 2016, compared to around 6 million dying from tobacco use.

So, for every one terrorism fatality, we had 234 tobacco deaths.

To put it another way, if think ISIS videos and other terrorist propaganda deserve a vigorous response, we should probably also worry about the marketing and disinformation tactics of these gentlemen…

2. Climate change denial

Second, climate change denial.

In 1838, Victoria was crowned queen in London. This was before the telegraph, so by the time the news was carried here by steamship, it took 14 weeks for Singapore newspapers to publish the news of Queen Victoria’s coronation.

Today, we are in the age of almost instantaneous global communication so we’d assume people got the message faster.

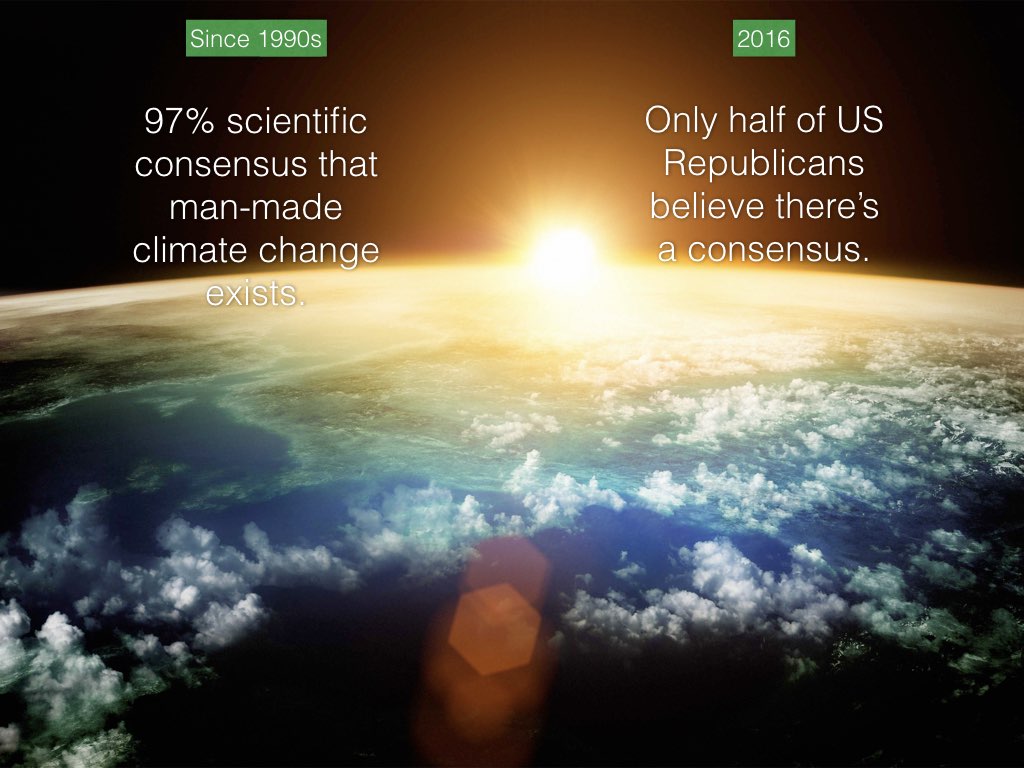

Since the 1990s, some 97% of scientists agree that manmade climate change is real. Twenty years later, many Americans still don’t know about it.

The dynamics of the climate change debate are broadly similar to the tobacco crisis. Conservative groups and energy corporations have for many years conducted disinformation campaigns to sabotage efforts reduce fossil fuel emissions. One key strategy has been to manufacture doubt about the strong scientific consensus about the existence of man-made climate change. Considering it gets harder and harder year by year to address the problem, the cost of this perception gap is mindboggling. Public knowledge and therefore public policy is lagging behind the science by one or two decades with probably catastrophic results.

3. Hate propaganda

Third, hate propaganda always employs disinformation tactics. Behind every genocide, ethnic cleansing, behind calls to get rid of immigrants or suppress a religious sect you will find the deliberate propagation of lies.

There are limitless case studies we can draw from. Let me start with our favourite newsmaker, Donald Trump.

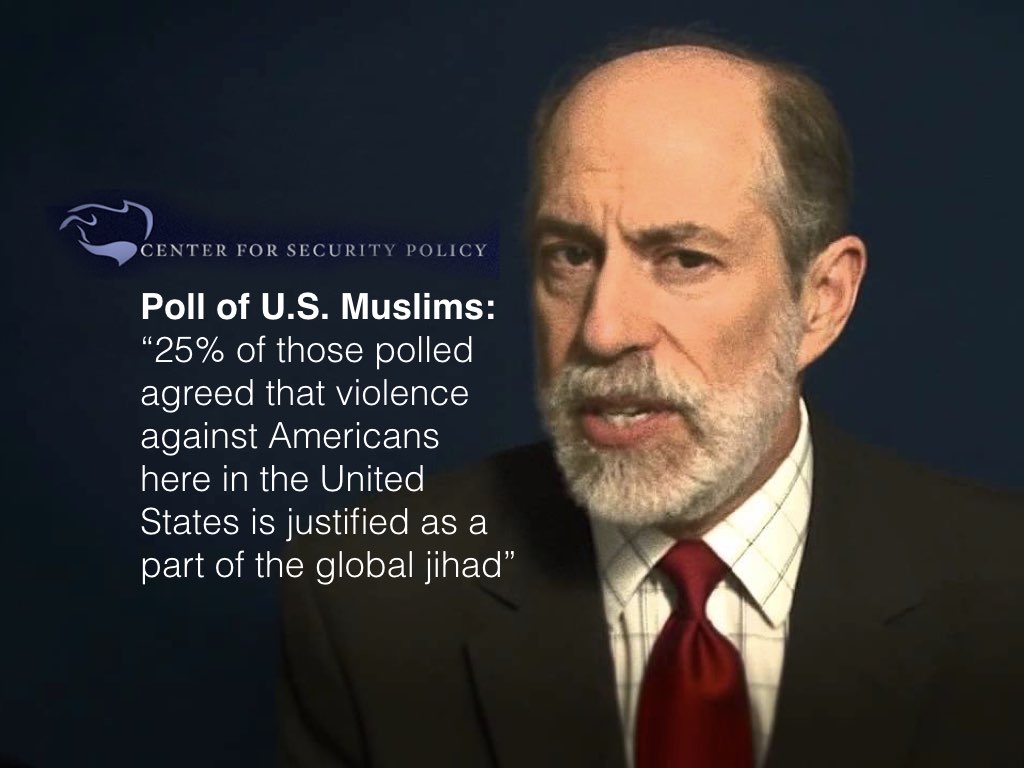

Here’s one example of how fake news feeds into the national conversation. The US has a number of think tanks that are devoted to generating disinformation about Muslims. One of the leading ones is the Center for Security Policy, which has been labelled by the country’s most respected hatewatch group, the Southern Poverty Law Center, as an “extremist organisation”.

According to a CSP poll, one-quarter of Muslims believe in violent jihad against Americans. Obviously, this poll has been debunked as totally unreliable. But the data was cited by Trump when announcing his plan to ban Muslims from entering.

Even some anchors from the rightwing Fox News have tried to correct Trump.

The American media did the right thing with this. Most checked, realised it was nonsense and so didn’t give it publicity. A few ran the story with the correct facts to tell readers that Trump was lying, again.

Indian media are normally very careful about reporting what they call communal issues. But that doesn’t stop the flow of hate propaganda, because this can always spread through direct marketing in the form of political rally speeches or grassroots campaigns.

Here is one example of clever disinformation that I write about in my book, Hate Spin. It’s the “love jihad” conspiracy theory.

The story is that young Muslim men are seducing away innocent Hindu girls and then forcing them to convert to Islam.

The grand plan is to turn India, which is now almost 80% Hindu, into a Muslim nation.

One of the most ingenious aspects of this disinformation campaign is that many of the flyers and posters will carry a hotline number [circled above].

If you see a hotline number, you will assume that this must be a real problem, because why else would anyone set up a hotline.

The worst riots in India before the 2015 election were in a place called Muzaffarnagar, and subsequent investigations showed that the love jihad narrative had been deliberately stoked up to turn a minor fight into a full-scale riot.

4. US conquest of Iraq

Fourth, the US conquest of Iraq.

This was an invasion built on a set of lies: that Saddam Hussein was developing Weapons of Mass Destruction, and that he was supporting Al Qaeda.

These were not innocent intelligence errors. We now know there was conscious suppression of contrary intelligence, the boosting of theories known to be dubious, for the deliberate purpose of misleading the American public as well as the international community that there was an urgent need for a military invasion.

Since 2003, this conflict built on lies has claimed around 4,500 lives on the American side and maybe 400–500,000 Iraqis.

Which still means, by the way, that if you want to use disinformation purely to kill people rather than to conquer territory, it’s still more efficient to market tobacco than to sell a war.

Observations

From these four cases, let me make a few preliminary observations.

First, disinformation often exploits people’s inability to process risk. Even with life-and-death matters like catastrophic climate change and epidemics, people have a hard time interpreting statistics. To make matters worse, disinformation merchants are exploiting people’s statistical illiteracy to pump out fake data.

The scientific community is especially bothered by this, because they often have the facts and figures for people to act on, but people are not absorbing the message. So there are a number of research centres working on this problem of risk and evidence communication, and I think these efforts should be part of the menu of solutions we should be looking at.

At the most basic level, we should be a lot more careful about how we visualise data. Here is an example of an elementary mistake.

The graph makes it look like the green bar is twice the height of the blue bar, but that’s only because the graph starts at 75.

If it were to start at 0, we get a very different and more accurate picture.

And if we add the margin of error, it suddenly becomes a different story: it could even be going down. Is this being too fussy? Are we expecting too much of media to be so careful with data.

No, Der Spiegel in Germany is already adopting some of these best practices, and there is absolutely no reason other than laziness that other art departments shouldn’t do the same.

Second, disinformation exploits fear of the Other. All over the world, people who want power know that it’s quite hard to offer real solutions for people’s problems, and much easier to use identity politics to win support. In this game, it’s always useful to have a minority to blame for your community’s problems. When you have a powerful military, you can go global with the blame game and start unnecessary wars.

Third, it’s naïve to believe that, without strong social interventions, people will be able to separate fact from fiction. Technology is making the job more challenging, because disinformation will be able to disguise itself more and more convincingly.

Fake news ecosystem

Let’s take a closer look at where fake news originates. In the examples we’ve looked at, we’ve seen disinformation coming from governments, from corporations, and from nonprofits and community organisations. The public, private and people sectors are all implicated.

The clearest form of fake news would be entire media outlets that are dedicated to deliberately deceptive content. Some have very clear ideological agendas; they are set up to promote a cause.

One of the most well known is InfoWars set up by the extreme right radio host Alex Jones. However, most are not driven by ideology but my money. They specialise in clickbait, sensational reports designed to draw maximum traffic.

Singapore had one very successful site like that, The Real Singapore, until it was closed down by the government and its two founders jailed. The effect of these purely profit-oriented sites can very similar to the partisan, ideological fake news outlets. First, it is much easier to be original if you carry fake stuff that others won’t. Second, it’s easier to be sensational if you prey on people’s fears and prejudices, such as anti-immigrant sentiment. So by default rather than design you end up with these clickbait sites selling the same rightwing intolerant disinformation as the ideological sites.

We distinguish these outlets from professional journalism that may be guilty of errors, but not deliberate ones. Is there are grey area between these two categories of fake news outlets and professional media? Probably.

For example, you could put Fox News programme “Hannity” in between. Perhaps Pakistani anchor Aamir Liaquat should be in the same category.

This picture is made more complicated by the fact that fake stories can leak into professional media.

This risk is increasing, because media are cutting corners by running news releases with minimal editing and checking. It’s very tempting for TV news programmes to use packaged video releases and B-rolls that are handed to them for free, allowing them significant manpower savings. An even bigger problem is the insertion of unchecked fake information into news stories, like the Press Trust of India story on Trump’s speech I showed you, or the thousands of stories about climate change that have quoted fake science.

Then there is social media, and the people formerly known as the audience, which contains the full range of types of information and disinformation.

And let’s not forget those formerly known as sources. These supply professional media with stories and information. But they also develop their own platforms that reach out directly the public.

These include disinformation sites like Jihad Watch, run by a well known anti-Muslim hate monger named Robert Spencer under something called the David Horowitz Freedom Center.

But of course there are also many sources disseminating high quality reliable information like the World Health Organisation.

Now the moment you see the world boxed up like this, any intelligent person will question the categories and the boundaries. Maybe the divisions are not so stark. Maybe we need to relook our definitions. And I agree. I think we want a realistic graphic depiction of our current information landscape, and its impact on us, here’s a very scientific diagram.

Strategies

So what can we do about a problem that’s coming at us from all angles. As I said at the start, I’m going to be quite modest about proposing solutions, because I don’t know what they are and I’m hoping to pick up some expert tips tomorrow. But let me make three very broad points.

First, in case it’s not already obvious, we are dealing with a kind of market failure in communication.

It’s naïve to believe we can trust the invisible hand of the information market to sort truth from lies. Yes, there are many invisible hands at work, but many of them are deliberately manipulating the market so disinformation succeeds.

The competition is becoming more unbalanced because as countries industrialise, media and communication professionals in the persuasion business—public relations, marketing communication, advertising—tend to outnumber professional journalists. Think of the impact on public understanding of issues.

Imagine a company trying to convince us a new chemical plant isn’t polluting when it is; chances are that a team of 10 professionals will be crafting the campaign for six months, and then when the news release comes out, you’ll have one reporter given four hours to write it up. What are the chances that the reporter will be able to detect what’s misleading or completely untrue in the story he’s been handed? Very slim. News organisations’ capacity to go through the required verification processes is not increasing.

This is where third-party fact-checking services are essential.

We also need help from internet intermediaries, Google, Facebook, Twitter and other platforms. Without abandoning the principle of net neutrality, these platforms have to find ways to discriminate against those who deliberately corrupt the meaningful exchange of information. One of the positive side-effects of Donald Trump’s victory is it’s made internet giants treat the problem more seriously.

Last year, if you googled “jihad” one of the top search results you’d get would have been Jihad Watch, the disinformation hate site I mentioned earlier. I was gratified to notice in preparing for this talk that “Jihad Watch” is no longer one of Google’s recommended links.

Instead you get various reliable sources, including professional news sites.

Of course Jihad Watch noticed this too and has condemned Google for it.

These disinformation campaigners can’t lose, because this action is being spun as another example of how the system is against them and therefore you believe in the cause you should donate to them, or in this case buy the book.

Second, although professional news organisations are not enough to fight against disinformation, they are obviously necessary. It should be quite obvious that the stronger the professional media sector the better society’s chances of combating disinformation. Journalists need the time and resources to produce meaningful stories that can counter fake news. I also suspect an experienced journalist’s gut feel can be extremely effective in spotting suspicious content.

Unfortunately, some of the same governments that claim to be very concerned about fake news are also busy making life harder for professional media. This is like trying to remove a brain tumour by removing the brain.

When governments do this, when they compromise the health of news media, I can only conclude that they are not seriously interested in fighting fake news. They are more interested in monopolising fake news. They want to be the only forces in society with the capacity to create and distribute disinformation.

States that sincerely want to fight fake news across the board would support or at least not hinder independent media; they would also invest in media literacy and critical thinking skills. As one academic has pointed out, debunking myths is not as effective as “prebunking” them. That is, helping people anticipate the kinds of disinformation that would be heading their way.

This is one think I’ve tried to do in my book Hate Spin: to help readers understand the way hate propaganda works as a political strategy, so that when they encounter it, they can immediately see what’s going on. The need for such critical thinking is obvious that if governments are not promoting it even as they complain about fake news, you have to suspect that they are less worried about the fake news problem than about citizens using critical thinking against them.

Don’t blame the audience

Finally, let’s go back to where I started, the troubling fact that many people are not interested in facts. Why have so many people turned their backs on truth and reason, not just in non-democracies where people may have limited access to the truth, but even in open societies designed to promote the free flow of information and ideas?

There’s an easy answer, and a more difficult answer. The easy answer is that people are dumb. Too many people are just too stupid. I say this is an easy answer because it lets us, the educated elite, off the hook. Journalists, professors and others who claim to believe in the power of reason can tell ourselves that it’s not our fault that others are not as smart as us. So we feel bad for society but good about ourselves.

But there is another answer that is more difficult to swallow. It’s that we have failed to use reason in ways that help our fellow citizens. The media as well as universities, and democratic institutions like courts and parliaments are the great post-Enlightenment institutions of reason; they have evolved rigorous processes such as professional journalistic routines, scientific methods, and rules of evidence to come up with robust answers.

Many have gotten very good at the exercise of finding answers. But they are not as good at identifying questions. Too often, their energies are devoted to issues that alleviate suffering or contribute to social justice. Most countries’ elite, quality media have done a much better job at telling us which 2017 luxury car model to buy than how government policies are affecting the urban poor.

The facts that the media seemed to really care about during what they now look back fondly on as age of truth were not the job prospects of the long-term unemployed or the healthcare woes of the urban poor, the ups and downs of the stock market, and whether a celebrity couple is breaking up.

If those were the truths the media cared about, is it really so dumb, is it really so irrational for people to opt out? Is it any wonder that a post-truth world looks no worse to them?

If this more difficult answer is the correct one, which I think it is, then the answer is not to give up on the basics of journalism. Striving for the truth through evidence based reporting is still the most powerful method we know to create reliable knowledge about public affairs.

What we need to do a lot better is to use that capacity to help those who are most at risk of being left out by progress. Our crisis is not because reason is no longer valid, but because of how it’s been applied in the service of the powerful.

State interventions

First, just because the internet is newish and its effects the most unfamiliar, does not mean that that’s where the most urgent and serious problems lie. Just because disinformation is most visible online doesn’t mean that’s where we should focus our interventions.

Second, we need to think about what the end goal is: is it to completely eliminate the harms that arise from fake news? Let’s think about how we manage other harms that our societies face. Think about the fact that every other day, a human being dies on Singapore roads. There’s a simple way to slash traffic fatalities to almost zero, which would be lower the maximum speed limit to 10 km/h. Clearly we’ve decided implicitly as a society that we can tolerate 200 deaths a year in return for more fluid transportation. And we’re making that kind of trade-off routinely: higher risk in returns of more choices.

So it shouldn’t be considered radically outrageous to say that we should learn to live with a certain amount of pollution in our communication space in return for our freedom of expression. There are some areas in which our threshold can and must be much stricter. Scientific information related to health, for example. Just as we have strict laws governing the advertising of pharmaceuticals and cures for illnesses, it may be reasonable to treat disinformation campaigns that sow confusion about health epidemics with the full force of criminal law. But that shouldn’t be the standard we apply in domains are that much more subjective such as political debate.

Third, the state can provide arms-length public funding for initiatives that build up resilience against disinformation, such as independent fact checking organisations and media literacy efforts; it can encourage higher quality journalism by supporting independent public service media like the BBC and independent press councils like Indonesia’s. The state has multiple policy instruments at its disposal other than punitive or restrictive laws and regulations. Governments have many body parts other than teeth.

– Originally published at https://www.mediaasia.info/journalisms-crisis-of-reason/