Main image: A world map showing territories in proportion to population size, by Mark Newman in Nature, 2006.

The case for provincialising the field

This is the text prepared for a Roundtable, Moving the Field of Political Communication Forward in Turbulent Times, at the International Communication Association Annual Conference, Paris, May 27, 2022. To download, visit SSRN.

I am grateful for the invitation to join this conversation about future directions for political communication as a field of study. I’d like to address the perennial concern about polcomm’s narrow focus on so-called WEIRD societies — Western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic. There are many scholars like me whose research straddles communication and politics in non-Western societies, who once assumed that polcomm was the place to be, and who quickly discovered that they could not feel at home there, finding intellectual sustenance instead in networks with names like “international” and “global” communication.

I know Western colleagues who have been strenuous and sincere in their efforts to diversify polcomm, but I also know that they would be among the first to agree that progress has been slow. Allow me to propose a radical shift in strategy. Rather than continuing to struggle to globalise polcomm and settle for incremental gains, why not respect the fact that there are many scholars doing good work within in this field as currently constituted. They are, not unreasonably, happy with polcomm the way it is. But respect should be mutual. And respect for scholars of the non-West requires that polcomm give up the pretence that it covers political communication in some generic or universal sense. De facto, it represents Western political communication. It should rebrand itself accordingly.

Many readers will recoil at the idea. It sounds like a regressive move, balkanising the field when we should be breaking down borders. Counterintuitively, I am hoping the opposite happens: the field as a whole will become more global when its most dominant regional grouping becomes more aware of its provincialism. A self-consciously Western (or North Atlantic) Political Communication Division of ICA (for example) would have to stop telling itself that it is working from some “neutral” subjectivity that is global by default. I am reasonably confident that it would then pursue with greater vigour collaborations with groupings of scholars of non-Western societies, who themselves would rise in status when polcomm stops claiming to represent them. My suggestion is in line with calls to “provincialise” western media scholarship as a way to interrupt “the unmarked (North Atlantic) histories and temporalities through which we engage and understand media and brings to the fore other temporalities of thinking media”.[1]

It may also sound like I’m advocating a retreat from liberal democratic values — succumbing to the global campaign being spearheaded by China and other illiberal regimes like my own country, Singapore. On the contrary, as I’ll explain later, I think universal liberal values will emerge more robust when we distinguish them more clearly from particular liberal democracies. Western academia’s self-absorption does the cause no favours.

Taking stock

Calls to redress the global imbalance in our field are nothing new. Georgette Wang’s volume De-Westernizing Communication Research is more than 10 years old.[2] De-Westernizing Media Studies by James Curran and Park Myung-jin is more than 20 years old.[3] In their 2014 review of this agenda, Silvio Waisbord and Claudia Mellado warned that “de-Westernizing” could become just another silo, an area of specialisation instead of a cross-cutting vision for the field of communication.[4] That’s exactly what seems to have happened, with colleagues in cultural studies and global comm seizing the initiative, while polcomm remains a chronic laggard.

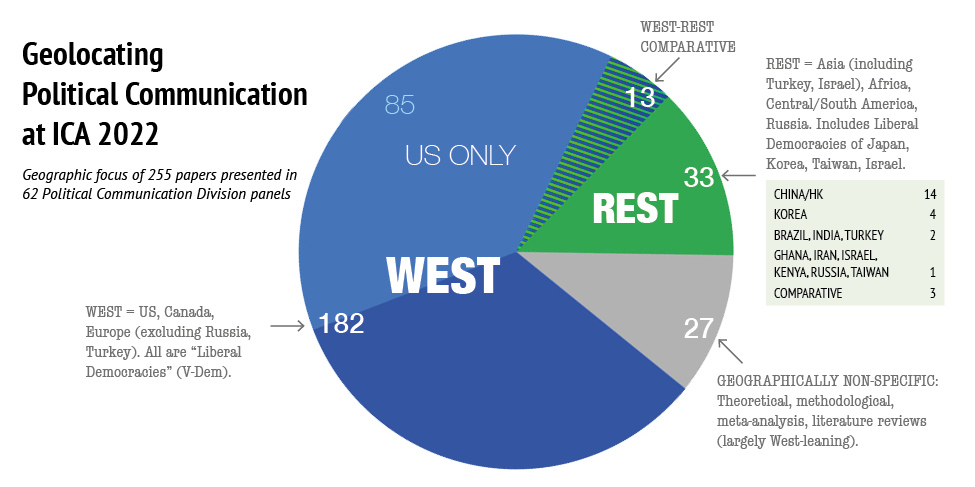

That, at least, was my impression. To test it, I took a look at the polcomm division presentations in this ICA conference, tabulating them by regional focus. I found that 71% of papers deal exclusively with Western liberal democracies, with almost half of these focusing solely on the United States (see the figure below).[5]

This is almost certainly an undercount, as I coded as geographically non-specific the roughly 10% of purely theoretical and methodological papers (the grey segment in the pie chart), even though such papers are mostly built on past literature that is mostly eurocentric. Also noteworthy is that despite all the good work that Frank Esser and others have been doing to promote comparative research, only 5% of papers compare countries of the West and the Rest.

The ICA journal, Political Communication, is very similarly constituted. In 2021, it published 38 articles, of which some 18% dealt with countries outside of the Western liberal democratic family.

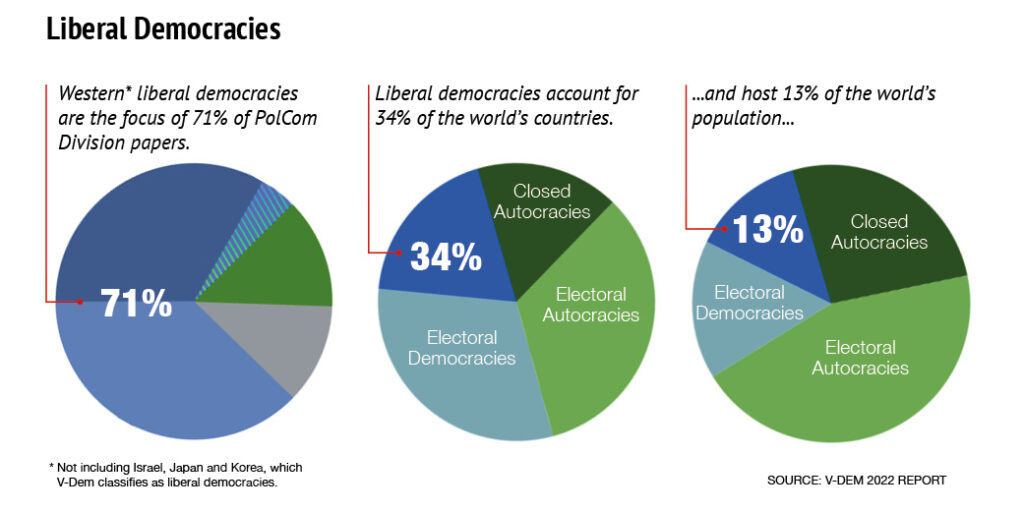

For a reality check, let’s compare polcomm’s orientation with how the nations and the people of the world are distributed. According to V-Dem, liberal democracies account for 34% of the world’s countries, and 13% of the world’s population.[6] Therefore, as shown in the figure below, countries that account for one-third of the world’s nations and one-seventh of its population currently take up three-quarters of ICA polcomm’s bandwidth.

Note that I am not talking about the full-on decolonial agenda, which would include theory building from the Global South, resisting the West’s epistemic dominance, and breaking the hegemony of the English language.[7] All this, frankly, may be a bridge too far for mainstream polcomm. I am merely talking about pivoting at the shallow end of pool, to align the field with the fact that most political communication occurs outside of the liberal west, which might therefore deserve more than 15-20% of the field’s attention.

The cost of this lacuna is greater for polcomm than it is for many other sub-fields. Colleagues who work at, say, the psychological level of analysis can claim with some credibility that their research on Americans is generalisable to other humans. The same cannot be said about the socio-political level where polcomm operates. The United States and Western Europe as a group includes no communist states, dominant-party systems, military juntas, theocracies, or kleptocracies. In none of them is government-controlled media a major player in the media landscape. Polcomm minus Asia and other regions makes it blind to entire media-political systems. It cannot claim to have a basic grasp of its subject.

What’s in the way?

Many journals and organisations have tried to globalise by diversifying their boards. Perhaps they are not doing so quickly enough — or maybe there’s a limit to how much a more diverse board can achieve without reforming dominant epistemologies and priorities. Whatever the reason, polcomm’s change has been incremental at best.

Two developments in the US in recent years made me hopeful that polcomm would open up to Global South perspectives. First, America’s autocratic turn made American scholars more interested in how authoritarianism operates. Second, the Black Lives Matter movement succeeded in sensitising many colleagues to their privilege. But, thus far, neither trend has spurred a quantum leap towards a more global field. In its interest in non-democratic societies, polcomm remains far behind other communication sub-fields — and even a decade behind its parent discipline of political science, which has generated a substantial stream of research on authoritarian resilience, for example.

Perhaps I was naïve to think that the trauma of the Trump presidency would rid polcomm scholarship of American exceptionalism. While polcomm now seems fully cognisant of America’s flawed democracy, scholars of other countries still struggle to get a word in edgeways. If American exceptionalism once emanated from liberal democratic triumphalism, it is now attached to liberals’ trauma at their liberal democracy’s decline. Thus, Americentricism remains intact, persuading scholars that their country is basically incomparable.

That same Americentricism may explain why the country’s racial justice movement has not had more of an impact in redressing global imbalances in academia. In theory, movements grappling with different forms of subordination — racial, colonial, class, gender, sexuality, and so on — could be said to be engaged in what Patricia Hill Collins calls complementary “resistant knowledge projects”.[8] These movements, notes Waisbord, “tear off the pretense of abstract, aseptic, neutral science” and “scrutinize how specific hierarchies and histories of power are woven into the production of academic knowledge, which in turn, reinforce inequalities and suppress or make alternative perspectives invisible”.[9]

In practice, though, these struggles are subject to a pecking order, with priorities set by those with more material and discourse power. Quite understandably, given the country’s history, the part of the American mind that cares about such things pays more attention to racial justice domestically than to global inequality. There seems to be an implicit assumption that, if only the US can cure its original sin of white privilege, other inequities will melt away. The flaw in this reasoning is that American global hegemony is not simply a function of white supremacy. Beyond white privilege, there is also a thing called American privilege.

The biggest barrier to globalising polcomm, though, is probably the social sciences’ methodological hierarchies. Many scholars have arrived at the not unreasonable conviction that experimental research (and in US political science, the testing of formal models) is the gold standard for arriving at causal conclusions about society. Other methods are assigned a lower status. Meanwhile, intellectual work and epistemologies outside of institutionalised academia are barely recognised. The problem is that quantitative studies presume and build on mountains of prior conceptual and theoretical development. You need to know already what you are counting and why, have some basic sense of how they are inter-related, and in what contexts they matter. Western polcomm has already done much of that groundwork. It possesses serviceable frameworks, theories and concepts within which to work, and can find rich lodes of data to mine.

I can therefore empathise with Global North scholars who are eager to dive in with sophisticated quantitative methods to tease out intricate causal relationships about their own societies in ever finer detail. I can also understand why these are the benchmarks required of some of their journals and conferences. For a mix of reasons, though, such groundwork is lacking outside of the Global North. Unless journal editors make a conscious decision to opt for a stimulating and methodologically eclectic cosmopolitanism over narrowly scientific notions of “rigour”, most Global South scholars will continue to be caught between a rock and a hard place. They can either let the methodological tail wag the knowledge dog in order to appeal to mainstream polcomm venues, or follow their curiosity and conscience using methods that polcomm is likely to view with suspicion.

What’s the harm?

When my graduate students complain about the lay of the land, I tell them not to be discouraged. Communication is not a discipline with a single dominant paradigm, but — to an increasing degree — a field of multiple, diverse traditions. More than ever before, specialised areas within communication have their own journals, conferences, organisations, and informal networks. Find your niche and you will be fine. If polcomm lacks diversity, that’s their problem.

Unfortunately, that’s not the whole picture. Scholars are not just free minds in search of intellectual homes. We also have bodies — individual and departmental — that require security within a neoliberalised higher education industry over which we have very little control. And it is in this context that polcomm’s false advertising — the provincial masquerading as global — causes actual harm to colleagues in the Global South.

Let me paint a scenario that will be quite familiar to many readers. University administrators and higher education authorities, intent on pursuing excellence according to what they take to be global benchmarks, institutionalise metrics to track progress toward key performance indicators. This game relies on proxy measures of quality, such as ranked lists of journals to determine whether a particular research output is “world-class”. Academics in the social sciences and humanities try to explain to administrators that many top-tier journals — like Political Communication — are primarily venues for Western research, despite their generic and global-sounding names. Administrators are unimpressed by this argument — since many of them come from STEM fields where top journals such as Nature and Science are less prone to cultural biases — and suspect their colleagues are just making excuses for mediocre work.

In some countries, the embrace of global metrics works hand in hand with political control, as my collaborators and I explain in our recent study of academic freedom in Singapore.[10] The Singapore state disciplines universities not only by punishing individuals who engage in critical public scholarship, but also by riding the neoliberal wave — rewarding work that the metrics say is globally excellent, although locally toothless. Higher education authorities, in partnership with compliant university administrators, have thus found they can safely channel academics’ energies toward top-tier journals. Academics willing to respond to these market signals end up going down the well-trodden rabbit holes that are of interest to American and European journal editors, rather than responding to Singapore’s intellectual needs.

The net effect, we point out, is a hollowing out of local capacity even as universities climb the global rankings. In the field of communication, the resulting distortions have been especially profound. Nanyang Technological University’s School of Communication and Information and the National University of Singapore’s Communications and New Media Department rank 5th and 26th respectively in communication and media studies.[11] But the number of colleagues in the two units who specialise in Singapore’s media/political system is zero. Meanwhile, the two universities’ politics departments have, between them, two fulltime faculty members who state a core specialisation in Singapore politics. They have more scholars specialising in the politics of Western democracies and China. The dominant, metrics-driven trend in global academia, indifferent to scholars’ social and political contribution to their own societies, allows Singapore’s autocratic regime to have its cake and eat it too: it can bask in global esteem even as it neuters critical scholarship.[12]

This is a suitable juncture to return to a point I mentioned in my introduction: the need for global academia to resist the line being pushed by China, Singapore, and other illiberal regimes that liberal democracy is a Western, not universal, value. As I argue in another ICA roundtable, we need to distinguish between, on the one hand, the analytical task of understanding the inner dynamics of non-Western systems (which will only happen if they are taken seriously as objects of study) and, on the other, normative evaluations of those systems (which does not necessarily require abandoning the twin liberal democratic pillars of freedom and equality).[13]

There is no shortage of influential voices from the Global South who exploit the confusion between the empirical and the normative, claiming that since the non-West is different, “Western” values shouldn’t apply to them. Let’s not be naïve. Sophisticated authoritarian regimes divide and rule. They control academia and media partly by creating a class of coopted professionals to whom they outsource the task of disciplining their respective sectors.[14] These spokesmen are entitled to their opinions, but we should not assume they represent their fellow citizens. There is no culture in the world — Confucian, Muslim, whatever — where everyone enjoys being dominated by unaccountable power. Well-meaning Western colleagues let down their freedom-loving peers in the Global South and play into autocrats’ hands when they over-compensate for the West’s privilege, slip into moral relativism, and throw shade at the universal applicability of basic liberal norms.

So, when I ask that the scholars in the West show more humility, I’m merely suggesting that they recognise the Rest as vast, complex, and deserving of deep study. When you trivialise, essentialise and condescend to the other 87%, you trigger deep memories of imperial domination and thus make yourselves — and fellow liberals in the Global South — an easy target for conservative nationalists the world over. Thus, the mainstream scholarship from actually-existing liberal democracies gives universal liberal democratic values a bad name.

I’ve detoured into the fraught academic terrain of illiberal societies like mine partly to explain where I part company with decolonial scholars: when they point accusing fingers at the Global North without simultaneously critiquing the role of Global South institutions in the subjugation of their own scholars. Old centre-periphery frameworks need to be updated to account for the considerable economic wherewithal of non-Western higher education hubs, such as Singapore and Hong Kong. These are among the richest economies in the world. Their universities do not need to remain in a dependent relationship with the West. They could choose to decolonise their approaches to the social sciences, instead of replicating the role of colonial elites a century ago and reproducing the unbalanced development of our field. They have chosen not to.

What can be done

So, if you are a Global North scholar, I do not think you are always or exclusively at fault for the marginalisation of Southern scholars. But I do feel you have a collegial responsibility to recognise the unintended consequences of your ways of working. In particular, I have tried to highlight here the harm you do through your implicit universalisation of the priorities and concerns of your small patch of the world.

It would help if you acknowledged the abiding provincialism of your sub-field, by renaming your publications and your events with the qualifier “North Atlantic” or “Western” or some other appropriate label. This principle should apply to the titles of your books and articles. Think about how Daniel Hallin and Paolo Mancini titled their works on media systems. Their sequel was titled, Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World. Logic would suggest that this had been preceded by a book titled, Comparing Media Systems in the Western World. But no, their classic study of American and European journalism was simply titled, Comparing Media Systems, period. This is just one of countless examples of how Global North publishers and authors treat the West as the default, while the non-West is assigned to a named ghetto.

This habit extends to how we identify and introduce individual scholars. A media scholar who specialises in, say, South Asia would usually be assigned a geographic tag, as “an authority on Indian media”, for example. Meanwhile, a peer who has only ever studied media in the (smaller) US context would be simply called an expert on media. I would not go so far as to call such slights micro-aggressions, but they are certainly symptoms of a systemic imbalance.

I’ve explained that there may be good reasons why polcomm remains focused on the liberal West. And I cannot fault Western colleagues for being drawn emotionally to the issues faced by their societies. For this reason, interrupting the flow of mainstream academic work with queries about intellectual biases can seem like “bad etiquette, akin to talking about religion or politics at the dinner table during the holidays”, as Waisbord puts it.[15] Therefore, I’m not inclined to knock on polcomm’s door, either to demand to be admitted or to instruct colleagues within how to rearrange their furniture. My suggestion is simpler. Just change the name at the entrance. Let’s accept that the field is what it is, and that what it is is Western Political Communication. Intellectual honesty and academic collegiality demand that acknowledgment, at least.

[1]. Shome, Raka. ‘When Postcolonial Studies Interrupts Media Studies’. Communication, Culture & Critique 12, no. 3 (1 September 2019): 305–22. P. 307 https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz020. See also: Willems, Wendy. ‘Provincializing Hegemonic Histories of Media and Communication Studies: Toward a Genealogy of Epistemic Resistance in Africa’. Communication Theory 24, no. 4 (2014): 415–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12043.

[2]. Wang, Georgette. De-Westernizing Communication Research: Altering Questions and Changing Frameworks. Routledge Contemporary Asia Series 25. London ; New York: Routledge, 2011.

[3]. Curran, James, and Myung-Jin Park. De-Westernizing Media Studies. Communication and Society (Routledge (Firm)). London ; New York: Routledge, 2000.

[4]. Waisbord, Silvio, and Claudia Mellado. ‘De-Westernizing Communication Studies: A Reassessment’. Communication Theory 24, no. 4 (1 November 2014): 361–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12044.

[5]. My “Western liberal democracy” category includes the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand. I excluded Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, which are liberal democratic but not Western.

[6] Boese, Vanessa A., Nazifa Alizada, Martin Lundstedt, Kelly Morrison, Natalia Natsika, Yuko Sato, Hugo Tai, and Staffan I. Lindberg. Autocratization Changing Nature? Democracy Report 2022. Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem), 2022. https://v-dem.net/media/publications/dr_2022.pdf

[7]. Chakravartty, Paula, Rachel Kuo, Victoria Grubbs, and Charlton McIlwain. ‘#CommunicationSoWhite’. Journal of Communication 68, no. 2 (1 April 2018): 254–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy003; Mohammed, Wunpini Fatimata. ‘Dismantling the Western Canon in Media Studies’. Communication Theory 32, no. 2 (1 May 2022): 273–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtac001; Willems, ‘Provincializing Hegemonic Histories’.

[9]. Collins, Patricia Hill. Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Duke University Press, 2019.

[8]. Waisbord, Silvio. ‘What Is next for De-Westernizing Communication Studies?’ Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2022.2041645.

[10]. AcademiaSG, Academic Freedom in Singapore: Survey Report. August 18, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.sg/ academic-freedom-survey-2021/, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3905623

[11]. QS World University Rankings by Subject 2022: Communication & Media Studies, https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/university-subject-rankings/2022/communication-media-studies.

[12]. George, Cherian. ‘Singapore’s Powerhouses Neglect Local Intellectual Life’. Times Higher Education (THE), 11 January 2018. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/singapores-powerhouses-neglect-local-intellectual-life; Holden, Philip. ‘Spaces of Autonomy, Spaces of Hope: The Place of the University in Post-Colonial Singapore’. Modern Asian Studies 53, no. 2 (March 2019): 451–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X17000178.

[13]. Panel: The Elephant in the Room: ICA and Non-Democratic Values Systems, International Communication Association Annual Conference, Paris, May 30, 2022.

[14]. For an excellent, early account of such practices, see Haraszti, Miklós. The Velvet Prison: Artists Under State Socialism. Tauris, 1988.

[15]. Waisbord, ‘What is next’.