Thoughts prepared for a session on Journalism Education in Myanmar, at the East-West Center International Media Conference in Yangon, 10 March 2014.

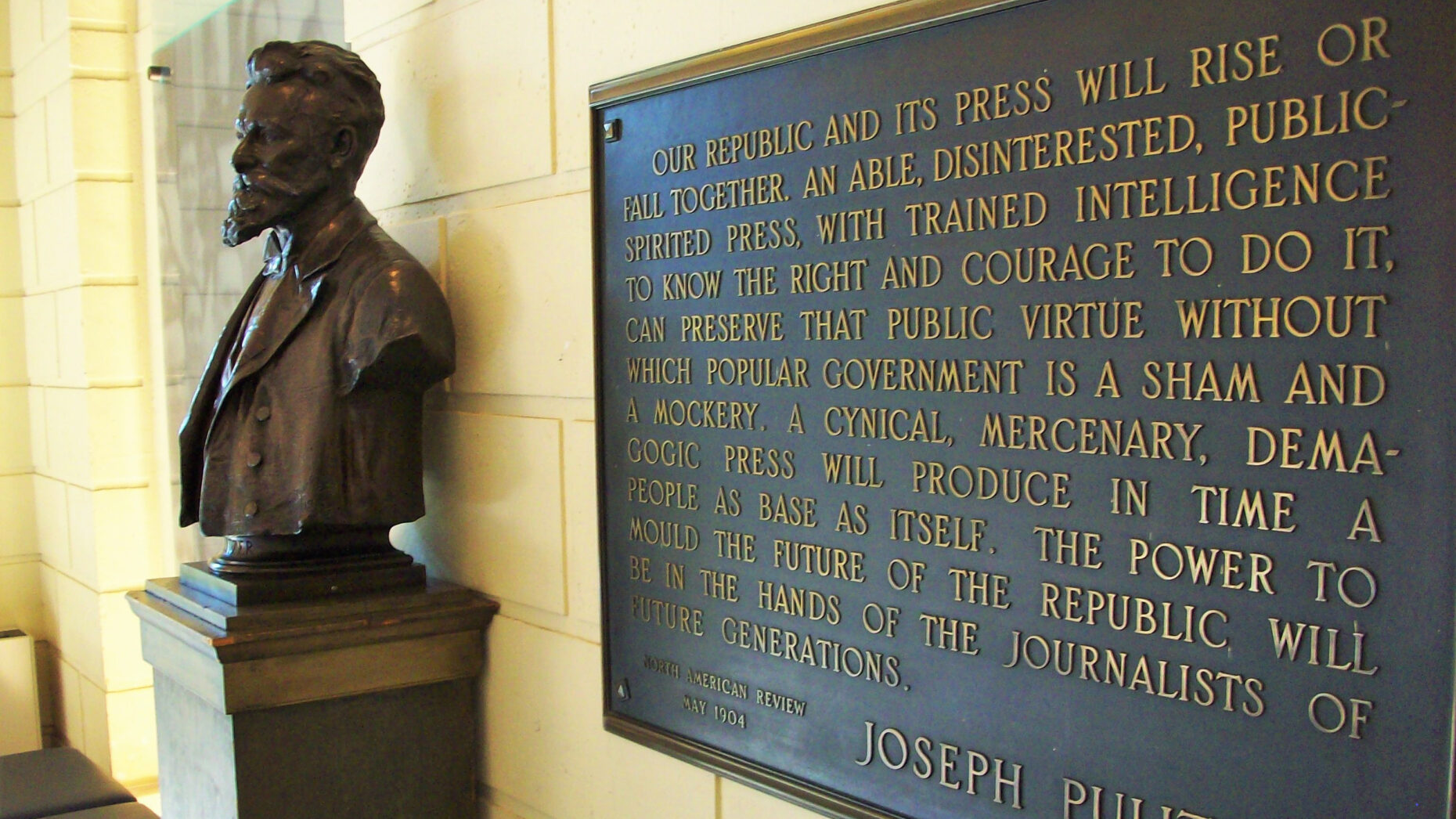

More than a century ago, newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer penned an intellectual defence of the college of journalism he was endowing at Columbia University in New York. Apart from the fact that a media mogul back then would have the patience to pen a 42-page essay in a scholarly journal, what is remarkable about his piece in the North American Review is how little the vision has changed for journalism as a course of study at university.

Few today would argue with his assessment that society could not afford to leave to chance the education of “the most exacting profession of all – the one that requires the widest and the deepest knowledge and the firmest foundations of character”. After Columbia, university-based journalism schools proliferated in the United States and then across the world. In most cases, their scopes were broadened (and often overwhelmed) by the addition of programmes in film, advertising and public relations, and the social scientific study of communication.

The key continuity since Pulitzer has been the idea that producing competent and principled professional journalists is the best way universities can raise the quality of journalism. Thus, journalism schools have been in the business of trying to improve journalism one journalist at a time.

This paradigm was rightly criticised, largely from the left, for neglecting more macro-level, structural impediments to quality, such as commercial influences on media. Some programmes responded by adding critical media studies to the mix. However, the main thrust of journalism programmes remains serving industry rather than interrogating it.

Pulitzer was not blind to the fact that the media owner has more power than the individual journalist over their product. But even if an editor does not own his medium, “every editor can be at least the proprietor of himself”, choosing to resign rather than sacrifice professional principles, he noted. He was firmly opposed to the idea of a college of journalism teaching business management – it should be “anti-commercial”, exalting “principle, knowledge, culture, at the expense of business if need be”.

Such a church-state separation between editorial and commercial functions has had strong intuitive appeal. And, in the 20th century context of booming newspaper markets, it was quite tenable for journalists and journalism educators to avert their gaze from the dirty business of economic sustainability – the money would flow in anyway.

The new challenge

Today, of course, we can no longer take for granted the financial wherewithal of journalistic enterprises. In mature markets, newsrooms are being slashed or killed off. And even in Asia, where markets are still growing, owners’ hunger for bigger margins is forcing news businesses to cut corners. As digital technologies force the industry to restructure, marketing and business development arms are setting the agenda, aided by consultants from outside the journalism profession.

The well-intentioned church-state separation has had unintended consequences for journalism education. Some universities do have media management programmes, but these have tended to grow out of business schools or communication schools’ non-journalism departments – those that have fewer scruples about being in bed with the agents of market forces.

The result of all this is that today’s journalism schools have had little to say about the central question facing the profession:

How can public interest journalism of strong professional integrity be produced sustainably within severely restrictive market conditions?

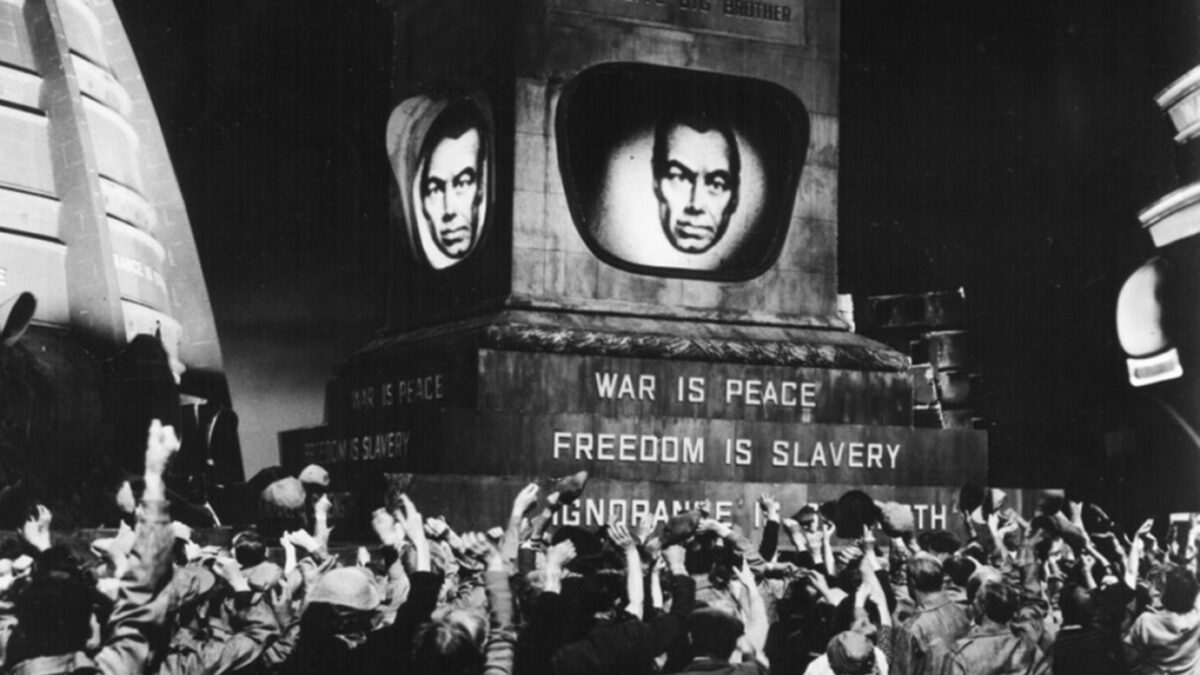

We need to reconcile ourselves to a world where journalists are expected to do more with less. But, if corners have to be cut, we need to be uncompromising about which ones must remain intact. Many media owners and managers are choosing to innovate in ways that undermine professional integrity – particularly by blurring what should continue to be a screamingly obvious line between stories produced with only the public interest in mind and content created to please advertisers and others.

Journalism schools need to enter the debate, robustly defending the value of free and independent journalism, but also offering answers for how quality can be practically sustained. In the US, there have been calls for universities to actually enter the business of producing journalism. In Asia, this is probably unnecessary and unwise.

Instead, media schools can help develop and promote:

• innovative business models (including non-profit approaches and non-traditional commercial revenue streams);

• the adoption of new cost-saving technologies; and

• the harnessing community capacities (including NGOs, citizen reporting and inter-media collaboration).

Innovative projects are already being carried out across Asia, often with the support of international foundations that are engaged in media development. Some, like Malaysiakini and the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, are well established; many are unproven start-ups. What is lacking is systematic and independent assessment of these experiments and knowledge sharing. Journalism schools should be the natural home for such work, conducting original research, convening events and creating resources to share best practices and explore cutting edge ideas.

Conventional journalism training is still as essential as ever, but it is not enough. Programmes tend to assume that there are well-resourced newsrooms waiting at the other end of the pipeline, ready to deploy well-trained professionals to the task of serving the public interest. This may have always been an illusion, but the suspension of disbelief is no longer morally defensible, knowing what we now know about the state of the news industry.

Too often, after securing formal qualifications or attending capacity building workshops, journalists are unable to apply their new skills or ethics. Denied a living wage, reporters may resort to “envelope journalism” and other corrupting practices. Elsewhere, they must cope with “paid news” and other management-led innovations that violate hallowed J-school principles.

In many small and under-developed markets, even the main media outlets may find it hard to support professional journalism. As for large markets with abundant ad dollars, smaller alternative projects that are required to provide diversity, including ethnic media, may struggle to survive.

In such contexts, it is not enough to train excellent individual journalists and just hope for the best. The absorptive capacity to make the best of that quality is critically lacking. Universities should help build the knowledge that will help editors and media entrepreneurs develop the sustainable independent media organisations that remain indispensable vehicles for public interest journalism.

– Originally posted at https://www.mediaasia.info/media-sustainability-why-j-schools-must-go-upstream/