Even with abundant information and the removal of censorship, truth may not prevail. This the edited text of a plenary address to the IFLA World Library and Information Congress in Singapore, 20 August 2013.

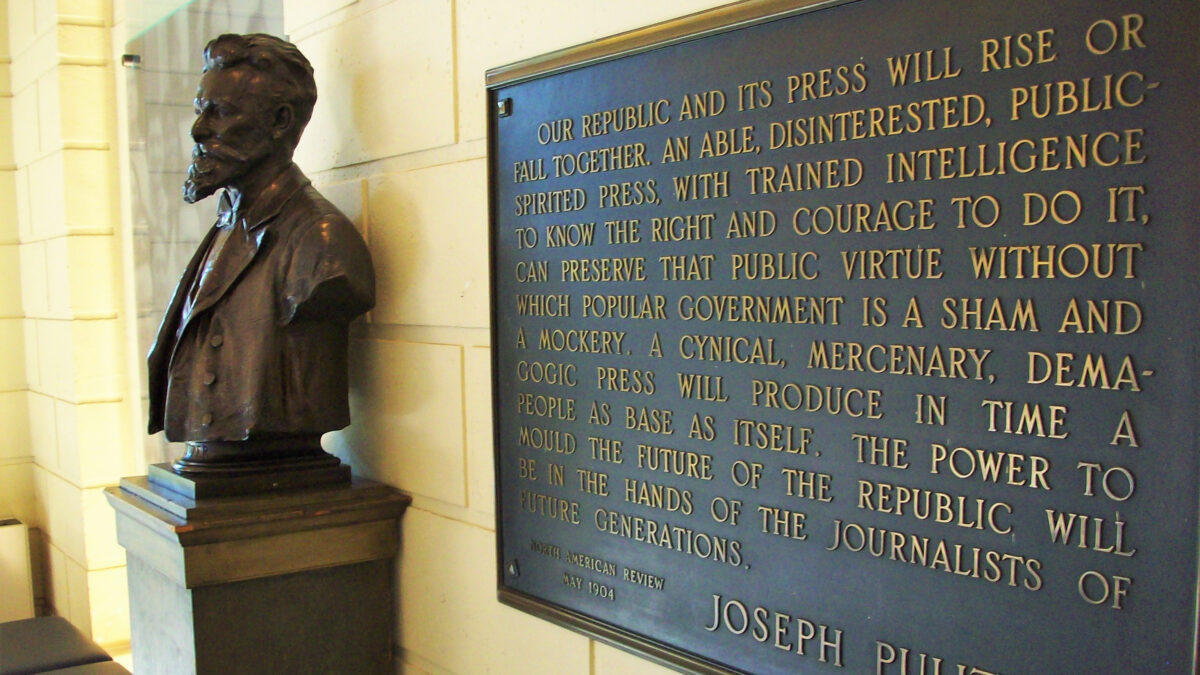

Journalists and librarians share a faith in the power of public knowledge. We wouldn’t be doing what we do if we didn’t believe that putting more information out there to more and more people will eventually lead to the betterment of our societies. Public knowledge is required for the exercise of public reason – collectively applying our minds to discussing our shared future, instead of letting small groups of men make important decisions for all of us in secret. This assumption about the value of public knowledge is so deeply embedded in our respective vocations that we usually take it for granted.

Indeed, we have no good reason to reject this belief. The question I’d like to explore is not whether a more informed society is a better society – the answer is as clear as the difference between North Korea and South Korea – but whether blind faith in this equation has led us to assume that knowledge is not only necessary but also sufficient. I want to argue that information cannot do the job on its own. We also need a professional and institutional commitment to public knowledge that is strong enough to counter forces around us that are intent on perpetuating popular ignorance and thwarting the exercise of reason. This is a lesson we can draw from recent world events.

The fog of war

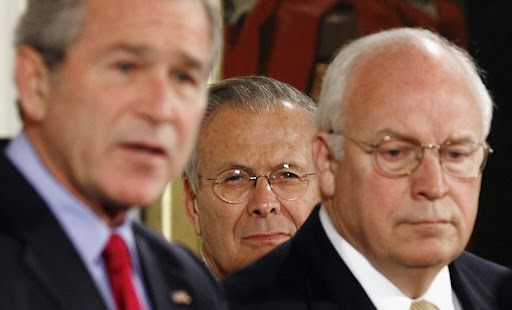

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the Iraq War. Ten years ago today, newspaper front pages around the world reported a bomb attack on the United Nations office in Baghdad that killed more than 20, including its Brazilian head Sérgio Vieira de Mello. This was one of the early signs that it was not yet “mission accomplished” for the US and its allies. But what was far more troubling than the exaggerated claims about how well the war was going was how easily the Bush Administration misled the American public into accepting the rationale for war in the first place.

According to the US government, Iraq posed an imminent threat to world peace and security because of Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction programme and his ties to Al Qaeda. With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that both allegations were false. But, even at the time that these claims were made, they were highly questionable and should have been interrogated by a press that had been granted constitutional freedoms precisely to protect the public from the tyranny of official untruths.

The failure of even respectable news organisations like the New York Times and Washington Post to speak truth to power in those critical months before the start of the war weighs heavily on the collective conscience of professional journalism worldwide. US journalists did not lack the freedom or the resources to challenge their political leaders’ view of the world. Yet, even they could not make this capacity count as their nation approached the life-or-death precipice of war.

A year before the invasion of Iraq, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld described the state of knowledge about Iraq’s WMD with what has become a classic quote: “There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.”

Rumsfeld left out a fourth category that forms a central concern of this essay.

The unknown knowns.

These are the things of which reliable knowledge is out there – yet it is studiously avoided, because the truth is too inconvenient to some.

The threat that Iraq posed to the world was less of an unknown unknown than an unknown known – UN weapons inspectors were providing knowledge that turned out to be correct, but these available truths were rendered opaque by the Bush administration. The knowable became unknown.

Of course, truth avoidance is a tendency we are all familiar with in our personal lives. Some of us are quite skilled at ignoring what we know to be true about the value of diet and exercise.

But I’m more interested in what happens at the societal level. Why do societies not act on available knowledge, even when the stakes are very high? One obvious reason is censorship. When the powerful monopolise knowledge and stop it from going public, preventable disasters follow. The Nobel Prize winning economist Amartya Sen has famously pointed out that prolonged famines have only ever taken place in countries that lack democracy and independent media. Mass starvation within a country is ultimately a distributional crisis rather than about an absolute lack of food, so it does not occur when governments can be held accountable through free elections and a free press.

However, the Iraq War case suggests that even where there are constitutional prohibitions against censorship and where information flows as a right rather than as a rare privilege, unknown knowns can still wreak havoc. It was not censorship as such that allowed untruths to win. For some other reason, the much-celebrated marketplace of ideas – where claims are supposed to be tested by open competition, leaving falsehoods rejected – failed, with thousands of lives lost unnecessarily.

Whitewashing history

Lest I seem to be focusing too much on the US, let’s look at Asia. India, the world’s largest democracy, is headed towards an election in which the main opposition challenge, from the BJP, is likely to be led by Narendra Modi, chief minister of Gujarat state since 2001. Under his watch, in 2002, Gujarat was the scene of India’s deadliest Hindu-Muslim violence in this century. The three-day carnage caused 1,000-2,000 or more deaths, with the minority Muslim community suffering the most casualties. Modi, a self-described Hindu nationalist, has not been found legally culpable for the violence on Muslims; but he has not been absolved of moral responsibility either.

Thanks to India’s vibrantly free press and civil society, Modi’s words and actions – as well as his conspicuous silences and inactions – before, during and after the riots are a matter of public knowledge. One would think that this would render him unelectable in a civilised democracy. Instead, his record has the status of an unknown known, as Modi continues his climb. Such lack of accountability is not new in Indian politics. The culpability of certain politicians in the ruling Congress party in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots continues to distress many Indians, but to no apparent effect.

Even closer to Singapore, there is Indonesia, which will hold presidential elections in 2014. Indonesia’s transition to democracy over the past 15 years has been awe-inspiring. The starting conditions were similar to Egypt: a large country under strongman rule for 30 years, with an interventionist army and unpredictable Muslim organisations at the grassroots, suddenly undergoing a democratic revolution. The recent unwinding of the Egyptian spring only underlines how remarkably positive Indonesia’s democratic consolidation has been in contrast. It has had a string of relatively peaceful elections, and democracy has been consolidated as the “only game in town” (to borrow a phrase from the literature on democratic transitions).

Yet, even Indonesia, with its strong tradition of independent journalism and one of the most active social media populations in the world, is not immune to the curse of unknown knowns. One of the declared candidates for the 2014 presidential election is Prabowo Subianto, a former special forces commander and son-in-law of the late President Suharto. In the late 1990s, men under his command kidnapped and tortured nine democracy activists – a charge for which he admitted responsibility after a government probe.

He has been reliably implicated in various other abuses, including the anti-Chinese riots that ravaged Jakarta in 1998. But, after being discharged from the military, Prabowo cultivated a new civilian, populist image. In 2009, he was the vice presidential candidate on a ticket that secured more than a quarter of the votes. He is now seen as a serious contender for 2014.

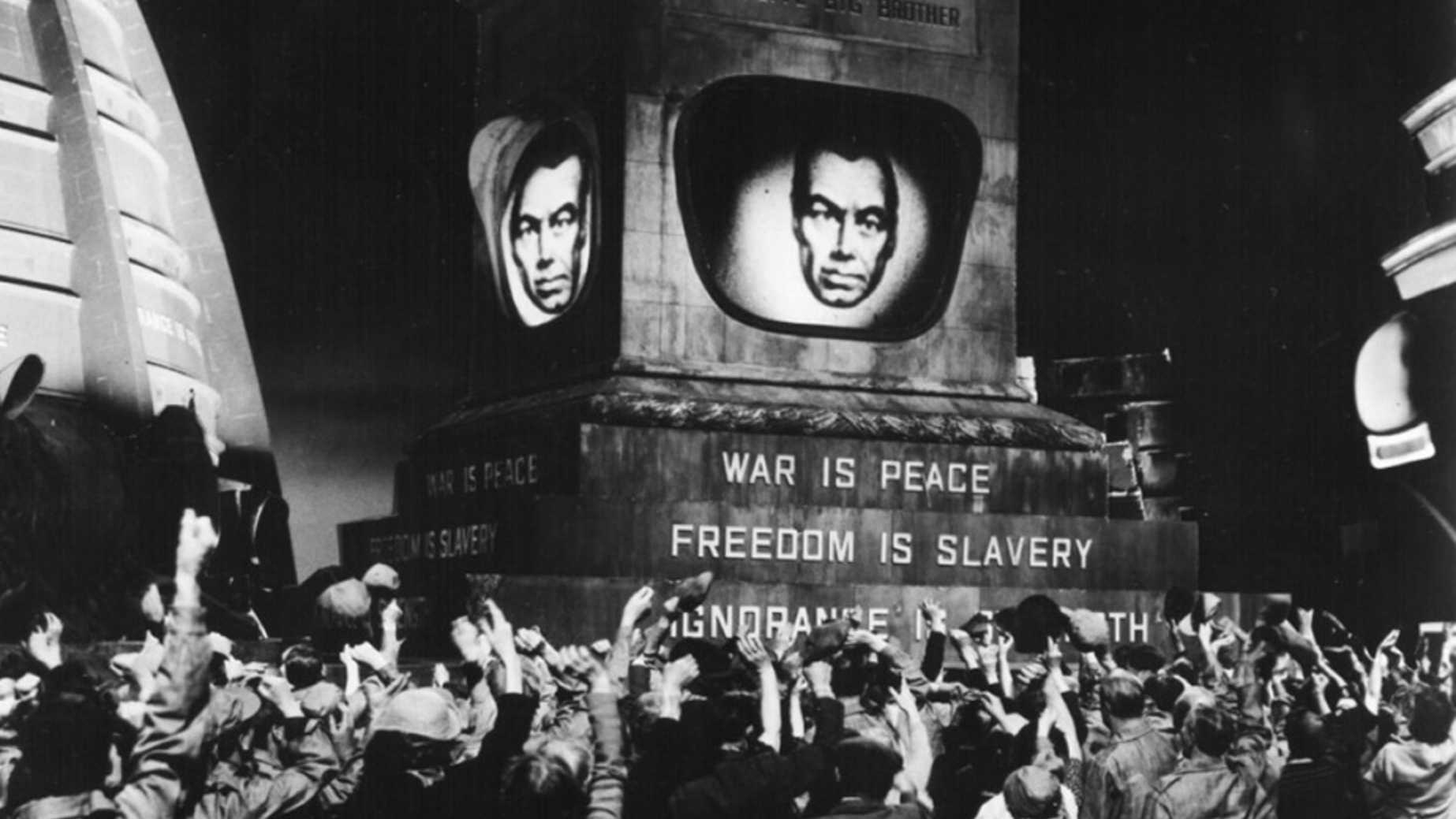

George Orwell’s novel 1984 talked about the lengths to which the totalitarian Party would go to manipulate citizens’ memories of the past. In his dystopian world, the “Ministry of Truth” was in charge of destroying all records that contradicted Big Brother’s current thinking, even to the extent of rewriting old newspapers. “Everything faded into mist. The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth,” Orwell muses. “If the Party could thrust its hand into the past and say of this or that event, it never happened – that, surely, was more terrifying than mere torture or death?”

But even Orwell’s penetrating gaze could not foresee the relationship between power and truth in the 21st century. It turns out that individuals such as Modi and Prabowo do not need to erase all knowledge of their disturbing pasts through Big-Brother-style censorship. Nor have they had to go through the cleansing and closure of any truth and reconciliation process. Instead, like Bush’s rationale for the Iraq War, these are cases of informational impunity – sometimes, the truth does not seem to matter as much as it should. This, to my mind, is a possibility even more terrifying than what Orwell conjured up.

The Age of Truthiness

Faced with such cases, one could conclude that people are just not that smart. The problem with this explanation is that it blames the victims, and distracts us from the active role played by politicians and other elites to ensure the unknowing of the known. In all these cases, we are dealing with skilled exponents of media and communication. These are not unsophisticated country bumpkins bumbling about the 21st century media landscape. They are masters of television and the twitterverse, backed by the best spin doctors money can buy and legions of young energetic volunteers.

Thus, the likes of Narendra Modi and Prabowo can count on their media machinery to help whitewash their pasts. The Bush Administration had Fox News to confuse and confound the American public. The phenomenal success of Fox News as a propaganda vehicle has been well documented. Its viewers were more likely to believe that Saddam Hussein was building weapons of mass destruction and supporting Al Qaeda. The more you consume its news, the less your grip on reality – which is the opposite of the effect that journalists are supposed to have.

In 2005, American television satirist Stephen Colbert coined the word “truthiness” to capture what the Bush Administration and Fox News seemed to be purveying – stuff that is designed to feel right at an emotional level, regardless of the actual evidence. Since then, journalists and media scholars have been talking about a new “Age of Truthiness”. News outlets like Fox spin a web of untruths into a kind of security blanket that ultimately makes viewers impervious to evidence and reason. Poeple seem quite content to live in a cosy, simulated world where cognitive dissonance is reduced by changing their perception of the facts to suit they feelings.

It is not just politicians that are engaged in sophisticated efforts to unknow the known. Corporate-backed campaigns downplaying the threat of climate change have ensured that, for more than two decades, public opinion and government actions have lagged behind the best available scientific knowledge and risk assessments. As a result, the most information-rich generation in the history of human civilisation may ultimately be responsible for its most catastrophically ignorant act.

In addition to political and corporate propaganda, the Age of Truthiness can be blamed on the seeping of entertainment values into news and current affairs. There has been a deluge of hybrid genres like infotainment, edutainment, reality TV and so-called “dramatisations based on real events”. Meanwhile, serious journalism is on the retreat due to the collapse of its business model. Fox News and dozens of similar channels in Asia and other continents can be said to have replaced traditional journalistic standards with what one scholar calls “branded political entertainment”. The net effect may well be to present public affairs through a prism that reduces complexity and moral ambiguity in order to present caricatures that audiences will find easier to root for or revile.

People power

At this point, we should look at the role of the audience and acknowledge that modern propagandists are often effective because they give the public what it wants. People power is usually celebrated as a democratic force, but it can just as easily express itself as an intolerant mob. This is one of the most disturbing aspects of so-called people power: the extent to which people are prepared to use their newfound voice not just to hold their rulers to account, but also to suppress the rights of other peoples – including weaker minorities. When parties in power tap into such grassroots forces, the results can be frightening for individuals and groups deemed to be enemies of the people.

Thus, the impetus to unknow the known frequently emerges not from governments but from populist pressures. Such forces express themselves in demands for censorship of literature, art and journalism, usually in the name of nationalism, ethnic pride or religious sensitivity. In China, for example, anyone who is seen as taking a soft line on, say, territorial disputes with Japan or separatists in Tibet must contend not just with state authorities but also with the frightening force of hypernationalist vigilantes at the grassroots. The British cultural theorist Stuart Hall coined the term “authoritarian populism” in his critique of Margaret Thatcher’s government, and it has since been used by scholars of China to describe a style of politics where illiberal regimes work with intolerant public opinion.

Meanwhile, Malaysian society has witnessed a string of ugly over-reactions against perceived insults to Islam, as the ruling party panders to the least tolerant members of its electoral base regardless the growing insecurity that religious minorities feel. And here in Singapore, the government’s fear of Christian conservatives is making an ass of the law and of human rights. It does not allow local TV to depict homosexuality in morally neutral terms. Citing the conservative values of Singaporeans, it has refused to repeal the colonial-era law against homosexual acts between consenting adults – the same law that the High Court of Delhi in India overturned in 2009.

The internet’s false promise

No discussion of public knowledge would be complete without considering the role of the internet, which we can now safely say has been the greatest revolution in communication since the printing press. Thanks to the internet, people are significantly more empowered now to create, share and search for knowledge. In many countries, including Singapore, the internet offers the best routes around state propaganda and the most effective antidotes to groups that want to impose their values on everyone else. However, its impact is often overstated and its capacity, exaggerated. While it continues to astonish and delight in the way it allows us to work smarter and have more fun, it has on the whole underdelivered on its promise to remake politics and public life. There are at least two reasons why this is the case.

First, it turns out that traditional centres of power, governments and businesses, are quite capable of mastering the internet to entrench themselves. In his 2011 book, The Net Delusion, Yvgeny Morozov documents how authoritarian governments the world over have exploited new media for their own political advantage. They are turning the internet into the “spinternet”, he says – a web where spin and propaganda are more important weapons than outright censorship.

China’s penchant for blocking sites is legendary, but this may not be the most effective weapon in its ideological arsenal. Instead, China has other tools of mass persuasion such as its so-called 50 Cent Party – an army of online commentators who steer and police discussions. A few weeks ago, a Chinese company released a video game in which players could step into the shoes of country’s armed forces and seize control of islands at the centre of its territorial dispute with Japan. The game was developed from a training simulator used by the People’s Liberation Army. This is propaganda so creative you’d think it came from Hollywood.

So, the first reason why the internet has not been as progressive a force as expected is that states are not as helpless as once assumed. The second reason is that people need to act in concert to get anything meaningful done. Unfortunately, although the internet was designed for mass collaboration, it has been far less successful in promoting collective action than a sense of individual empowerment. The internet immerses us in an information environment of infinite choice, and while this choice is extraordinarily liberating at the individual level, there does appear to be a social cost. The freedom to transcend geography and community to pursue one’s own interests too often results in a lack of attentiveness to what is going on in one’s locality.

Research has shown that even cable television had this effect. In the past, when people were dependent on a few general interest terrestrial channels, they tended to be exposed to the daily news even if this was not their favourite kind of content. But as people were able to tune in to specialised entertainment, sports, fashion and cooking cable channels, their exposure to news and hence their level of political knowledge declined. If even cable TV had done this, you can imagine what the impact of the internet is.

The effects are visible among undergraduates in my university, part of the first generation of so-called digital natives who receive more information from online sources and social media than newspapers or television. As part of a survey that colleagues and I conducted for a forthcoming chapter on social media, we polled our undergraduates on their levels of political knowledge. All were already of voting age, or would be by the next election. Yet, less than two-thirds knew how often elections need to be held in Singapore. Even fewer could answer a basic question about what happened in a historic election just the previous year.

On affairs outside of Singapore, our students were more knowledgeable about personalities in the West than about their neighbouring countries. More than half knew the name of the current British Prime Minister and three quarters could name the U.S. Secretary of State, but less than one-quarter could identify Malaysia’s largest opposition party, and less than one-third the Prime Minister of Thailand. What these findings tell me is that – especially in a small, English-speaking country like Singapore – the borderlessness of the internet is accentuating the global imbalance in news provision, such that even those who pay some attention to current affairs know more about the West than their own surroundings.

While it is good to think globally, people need to act locally. For this, it is absolutely essential to possess knowledge about the local – especially about both the diversity within your society as well as the common ground you share.

On the whole, of course, people in internet-rich societies are better informed than ever. And, you can choose what you want to be informed about. You are no longer constrained by other people’s tastes, interests or values; you can follow your heart, and this is extremely fulfilling at the individual level. But the risk is that the sum of individual choices results in a level of public knowledge that is too low to produce meaningful collective action, and renders us too easily manipulated by the powerful.

An information war

For all these reasons, those of us in the business of public knowledge may have been too complacent. I referred earlier to George Orwell’s 1984. Although it is not central to the plot, he does actually make passing reference to the challenge we face. The protagonist’s lover, Julia, is sexually liberated but illustrates the impotence of knowledge. Smith has evidence of Big Brother censorship and is eager to share it with Julia. But, Orwell writes: “If he persisted in talking of such subjects, she had the disconcerting habit of falling asleep.”

This makes Smith realise how the Party was capable of imposing its world-view on people: “They could be made to accept the most flagrant violations of reality, because they never fully grasped the enormity of what was demanded of them, and were not sufficiently interested in public events to notice what was happening. By lack of understanding they remained sane. They simply swallowed everything, and what they swallowed did them no harm, because it left no residue behind, just as a grain of corn will pass undigested through the body of a bird.”

True, there has been a positive global trend towards greater openness – pushed by democracy, markets and the internet – but we may have underestimated the forces actively working against Enlightenment values and the exercise of public reason.

Our naivety is reflected in the metaphors and mental images we use. For a century or more, we’ve imagined a “marketplace of ideas” as if people will always buy truth over falsehood if we just put our wares on the table and let competition work its magic. Since the digital revolution, we’ve talked about “information superhighways” and “information explosions” as if the main challenge is simply to organise and manage the flows.

What such images have in common is that they encourage an attitude of professional detachment and passivity. We assume we do not need to take a stand because some invisible hand in the marketplace of ideas will eventually get it right. In the alternative and I believe more realistic perspective I’ve suggested, some hands, visible and invisible, may be actively working to distract people from the public knowledge needed for effective democratic self-government.

An editor friend of mine, Kunda Dixit from Nepal, who has had plenty of opportunities to reflect on media and conflict, tells me: “The reason the truth gets eclipsed on social media is because moderates and democrats are tweeting, blogging and facebooking less than the bigots, chauvinists, racists and fascists.”

In the information wars, we may be on the side of truth. But whether we are on the same side as destiny is another matter.

Our response, I suggest, has to be a rediscovery of the public service tradition that lay behind the building of institutions such as public libraries, public broadcasting, and the social responsibility approach to professional journalism. These notions were taken most seriously at a time when information and bandwidth were still relatively scarce. Society’s dependence on the institutions of public knowledge was more obvious, and so they took their responsibility for helping to create a better society more seriously.

But when developed countries entered an age of apparent information abundance – coincidentally, around the same time that the neoliberal revolution gave birth to an era of market fundamentalism – we told ourselves that the public service paradigm was too elitist and paternalistic and not market-oriented enough. We started thinking of serving customers instead of nurturing a public. I recall that in the 1990s when I served a term as a board member of Singapore’s National Library Board, its chairman liked to speak of librarians as “information concierges” – he meant that they should be as customer-oriented as a knowledgeable concierge in a five-star hotel, to cater to a guest’s every whim and fancy.

I remember being quite impressed by this vision at the time. But, in hindsight, I can see that the ideal of a responsive information concierge, whether for librarians or journalists, falls short of what is actually needed – which is a much more proactive approach of cultivating a public.

The old paradigm sprouted great public service institutions like the BBC. In contrast, the media policies of countries that underwent the so-called third wave of democratisation in the 1980s and 1990s were gripped by neoliberalism and tended simplistically to equate free media with free-market media.

Critical research in media studies has shown persuasively the limits of unregulated markets in delivering the kind of journalism that democracy requires. Comparisons of selected North American and European countries suggest that those with robust public service media systems have better-informed citizenries than those with more commercially driven media. Scandinavians were found to know more about both domestic and international affairs than Americans, with Britain – with its hybrid broadcasting model – falling in between.

It is not the competence of the individual journalist that makes the difference. It is the moral purpose to which that capacity is put. When the media is organised around a clear public service mission to engage people in public affairs, rather to capture demographics desirable to advertisers through any means available – that’s when journalism begins to fulfill its democratic potential.

Fortunately, neoliberalism is beginning to lose its ideological grip. In discussions about saving the financially bankrupt American press or about laying the foundations for democratic media in Myanmar, it is becoming possible again to talk about not-for-profit public service media without being labelled a communist.

Coming along with this welcome shift is the small but growing school of thought calling for a morally engaged approach to truth-seeking. The methods of objectivity and neutrality are just that – methods; they do not tell us what is important to know and why. Without a clear sense of moral purpose, a normative vision, those of us in the business of public knowledge could see our efforts easily hijacked by those representing narrow commercial and political interests.

In Media and Morality, possibly the most important book on media and communication in this century, the late Roger Silverstone calls global media a “moral space”. We know the power of media, and with that knowledge must come an enlarged sense of responsibility. We need to find ways to ensure that “the public space that the media create is one which works for the human condition and not against it”, he writes.

Silverstone argues that a primary responsibility of media is to provide “resources for judgment”. Judgment, he emphasises, is much more than individual thought. It is a “talking through… a constant engagement with one’s own thought and that of others”. Public media must provide more than just “naked facts”; they must provide the resources for people to make judgments effectively.

There has been a dramatic increase in access to information that individuals enjoy thanks to the internet. But despite the increase in the volume and diversity of information – and partly because of it – our access remains mainly mediated, meaning that individuals rely on intermediaries to package and present what they want to know. These intermediaries have diversified – they are no longer one’s domestic news media organisations, but also include bloggers, forums and a host of other information providers from the public, private and people sectors – but they are still intermediaries.

And as long as information must be mediated, those with power, money, networks, organisational capacity and other resources will invariably have an advantage in the marketplace of ideas over those who don’t. The capacity to mislead for private gain has not been erased by the internet or any other communication tool. The role of journalists and librarians as guardians of public knowledge and public reason remains as important as ever.