This is the full text of my presentation at a Hong Kong University Law Faculty conference on the territory’s year-old National Security Law. Scroll to the bottom for the video.

I will argue for a political reading of the NSL’s implications for Hong Kong’s media freedom. In-depth legal analysis will only go so far.

I will also develop a second point: While the NSL introduces the legal possibility of extreme and total control, a comparative perspective suggests that what’s more probable is a system of selective censorship that I call post-Orwellian authoritarianism.

Third, as a Singaporean, I can never run away from this question: is today’s Singapore the Hong Kong of tomorrow? I’ll suggest that the Singapore model is hard to replicate, and that Hong Kong is more likely to converge with the far more numerous set of messy, raucous, semi-free and semi-closed media systems around the world.

First, let’s discuss how to read the NSL. From day one, legal analysts have pointed out that the law’s wording is vague and overbroad, and I am sure this will be a running theme in this conference.

At the heart of this controversy is a mismatch of expectations over how the state should deal with speech that it considers against the public interest. In particular, how it should use law.

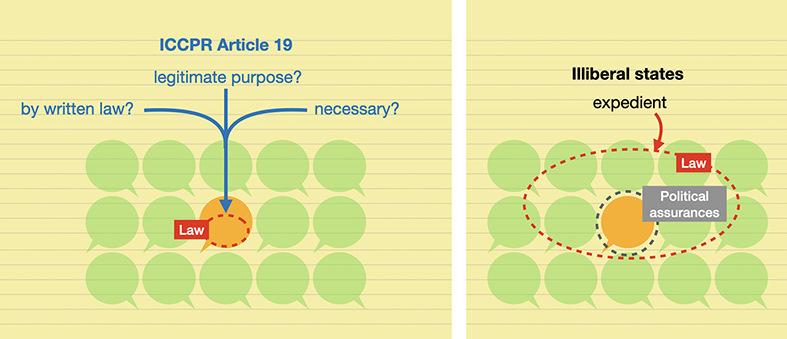

Under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, states can restrict freedom of expression, but restrictions must pass the so-called three-part test, to ensure that states do not engage in overkill.

Restrictions must not only serve a legitimate purpose — and national security is one of the purposes specified in the ICCPR — but must also be according to clearly written law, and be necessary and proportionate to achieve the stated ends.

It is often hard to tailor laws so snugly. ICCPR and ICCPR-consistent national constitutions require states to err on the side of freedom. This means courts often prevent the executive branch from achieving its goals solely through law. The government and must instead rely on other instruments — education and counter-speech, for example.

Most states, including many that have ratified the ICCPR, find the three-part test far too onerous. They would rather apply the simple test of expediency, and arm themselves with laws that give them maximum room for manoeuvre. This introduces the possibility of restricting or chilling socially valuable speech.

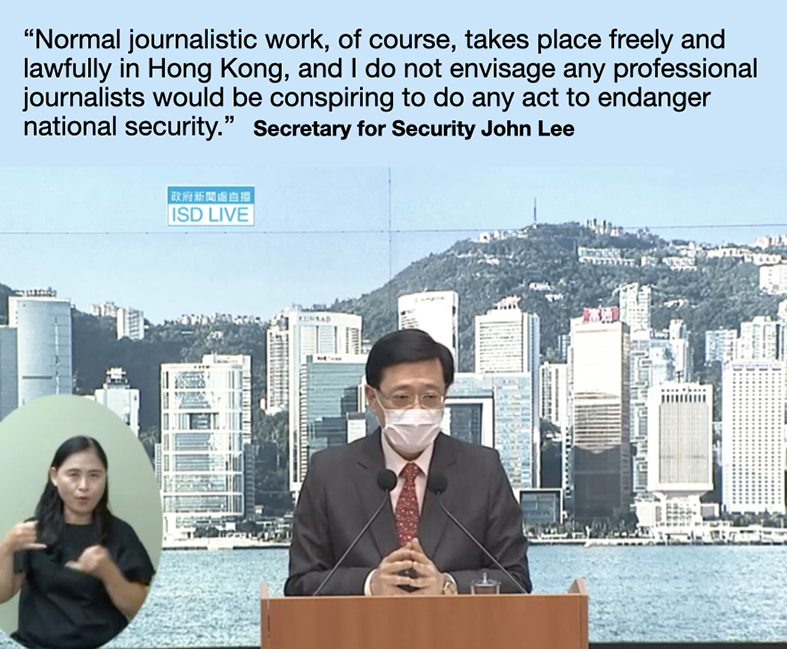

When accused of intending to abuse these powers, such governments provide political assurances that they will only use the law for the greater good, and that responsible media have nothing to fear.

We have seen this dynamic play out here in Hong Kong over the past couple of weeks. The government has tried to reassure Hongkongers that its actions against Jimmy Lai and Apple Daily have nothing to do with press freedom and are not a sign of things to come for other professional media.

With foreign governments weighing in, the government’s denials that last week’s events have anything to do with press freedom have only gotten shriller. And so this issue, like practically all important discussions about Hong Kong, has been sucked into the vortex of geopolitics and political polarisation.

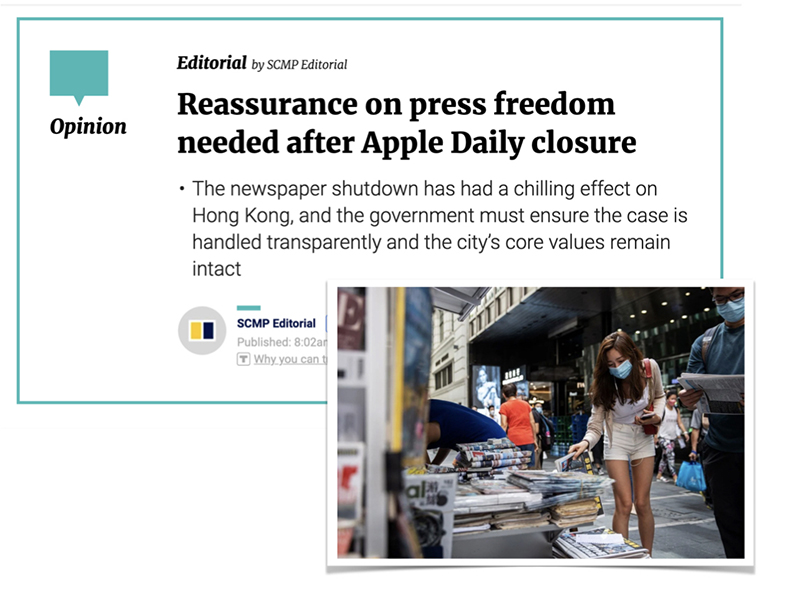

Since the government’s political pledges are not written into law, Hong Kong’s media fraternity remains concerned. The South China Morning Post said in its editorial last Friday:

“Media freedom goes to the city’s unique identity, competitiveness and success. In that regard the government must not use, or be seen to be using, this case to limit press freedom, including media criticism of bad policies and scrutiny of government performance. … there is no question the city is feeling a chilling effect.”

Talking to Hongkongers about events of the past year, I know that many of them find questions about where the red lines are to be incredibly naïve. They think that the only question is how quickly Beijing will implement one country one system and impose the mainland rules wholesale on the once-special administrative region of Hong Kong.

Indeed, Beijing’s “nuclear option” cannot be discounted. In the case of media, this would mean either communist-style full nationalisation of all print and broadcast media, or Singapore-style discretionary licensing, banning any media deemed troublesome and permitting one or two compliant media companies to function. The internet would be placed behind China’s great firewall. RTHK would be replaced by CCTV18–20 or whatever. All journalism schools, including mine, would be closed down or restructured.

I have no knowledge of Beijing’s intentions, but for the sake of non-Hongkongers in the audience I will just point out that there is another point of view in this city. It says that what we are seeing is an orgy of retribution against Hongkongers who used sovereign Chinese territory to invite Western powers into what should have been a private family quarrel.

According to what I’d call a “controlled burn” theory, Beijing wants to teach Hong Kong a lesson once and for all, and call the protesters’ bluff: “‘If we burn, you burn with us‘? No, Hong Kong will burn alone.”

If this interpretation is correct, then once the city is cleansed of the main forces behind the 2019 unrest, Beijing will be content with a new equilibrium that is different from the past, but still qualitatively different from the mainland. There will be no need for the nuclear option.

Which of these scenarios one believes is a matter of political judgment. In most jurisdictions without guaranteed freedoms, journalists use their experience to gauge if there room to take calculated risks. Hong Kong, however, is in a brand new situation with no precedents to guide us.

It may help to look elsewhere, since the authoritarian condition is obviously nothing new to the world’s media.

What comparative studies tell us

Our picture of authoritarianism is coloured by the memory of totalitarianism, often filtered through George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, written in the 1940s in the shadow of Stalin and Hitler. Orwell described a regime of absolute conformity; zero tolerance of alternative way of thinking; maintained by routine violence and fear.

Post-Orwellian authoritarianism is something I explore in a chapter in my forthcoming book, Red Lines, a global study of contemporary censorship that will be published this August.

I point out that resilient and consolidated authoritarian regimes, like China and Turkey, have tried to rely less on bans and jail terms and more on indirect and invisible methods of media manipulation — including using economic levers to inculcate self-censorship — that are more sustainable and less costly in the long run.

This is not an original insight. By the 1980s in the Soviet bloc, Miklós Haraszti observed the difference between the “primitive totalitarianism” of the Stalinist period and the mature state socialism of his times, where “sticks are exchanged for carrots.”

Around the same time, the ruling People’s Action Party in my own country was developing the art of using just enough force to get the job done without provoking levels of moral outrage around which opponents could mobilise. In my own writing 10 years ago, I called this “calibrated coercion”.

By the mid-2010s, media freedom monitors were reporting that modern authoritarian states were substituting violent repression with stealth censorship. Most of the academic work on Chinese censorship over the past decade has come to similar conclusions.

So, the notion that authoritarian regimes do not try to maximise repression is now mainstream.

Theorists suggest various reasons for this self-restraint. Here are just some of them.

First, states have moderated their expectations, and have come to understand that total information control is costly and probably unachievable.

Second, unlike Hitler, Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot, today’s authoritarian leaders tend not to have revolutionary utopian visions that require the vocal support of the entire population. Brainwashing is out. Distraction and depoliticisation is in. As long they leave politics to the state, people are allowed to consume and produce media that amuse them in myriad ways.

Third, resorting to spectacular and forceful repression can backfire. It can cause public outrage around which opponents can mobilise. Coercion, intended to inhibit people, can instead increase their resolve.

Fourth, an excessively punitive system results in such widespread cover-ups that even rulers end up in the dark about what is happening on the ground. In a market economy, businesses cannot survive if only good news is allowed to circulate.

Note that this theory is not premised on the presence of leaders who want to do the right thing. It’s assumes only that authoritarian states are learning organisations capable of doing the smart thing. States are not averse to the occasional use of direct and coercive censorship; but extreme methods are not necessarily the preferred or most routine form of control.

Political scientists have tried constructing elaborate models to establish the relationship between the likelihood of repression and various other factors such as the levels of dissent, regime stability, civil unrest, foreign scrutiny and so on. But overall, it is easier for historians to look back and explain why an authoritarian regime acted or didn’t act in the way it did, than for political scientists to predict their behaviour.

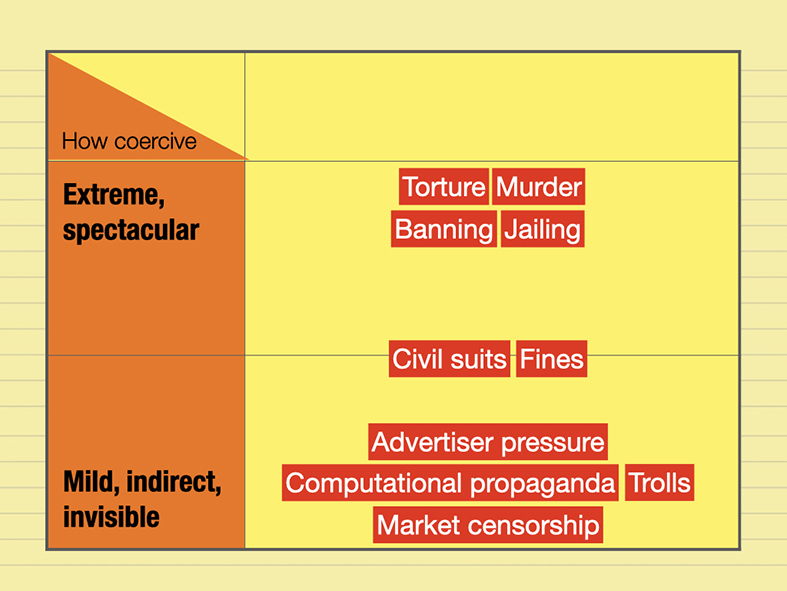

What we do know is that regimes have a wide repertoire of methods to choose from. Torture, murder, bannings attract headlines and international condemnation.

But precisely because these more violent methods get unwanted attention, states often use less extreme legal and administrative tools to discipline media, including civil suits, tax probes and so on.

Even less visible are economic, technological and populist tools, working with the market, with algorithms, and online and offline mobs.

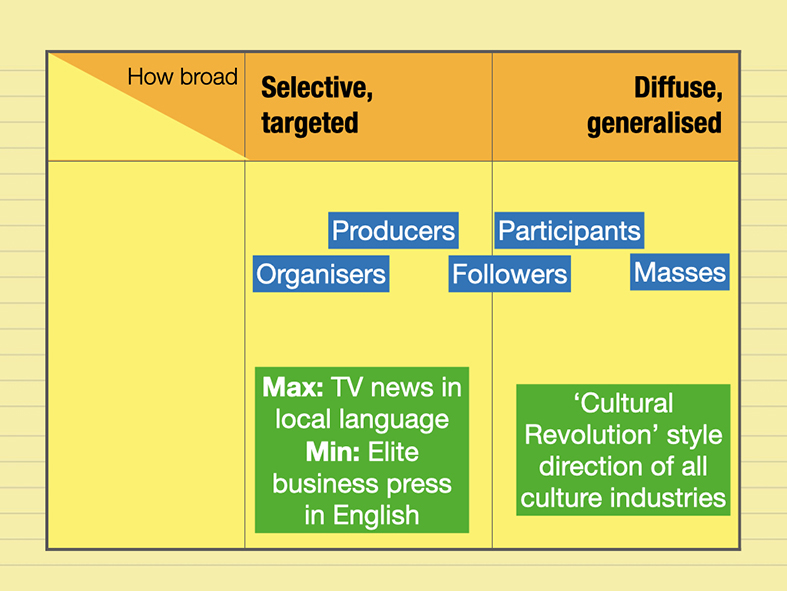

Regimes also vary the breadth of their interventions. We associate the Orwellian paradigm with mass indoctrination. Eeveryone is expected to be an ideological foot soldier of the revolution, and all media — even art, culture and entertainment — must not only refrain from political dissent but must actively generate propaganda. Neutrality is not an option.

Such totalising visions are now rare. There is strong censorship of organisers and producers of dissent, but the masses are mostly left alone to consume what in the past would be considered counter-revolutionary or heretical material.

Regimes tend to exercise strong control over the most influential mass media such as free-to-air TV news in the local language, but are willing to allow niche media such as English-language business press more room.

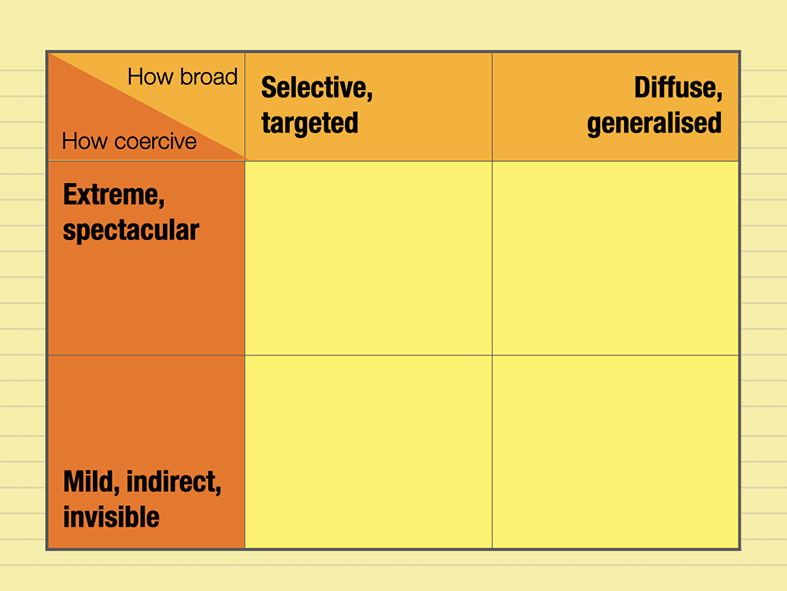

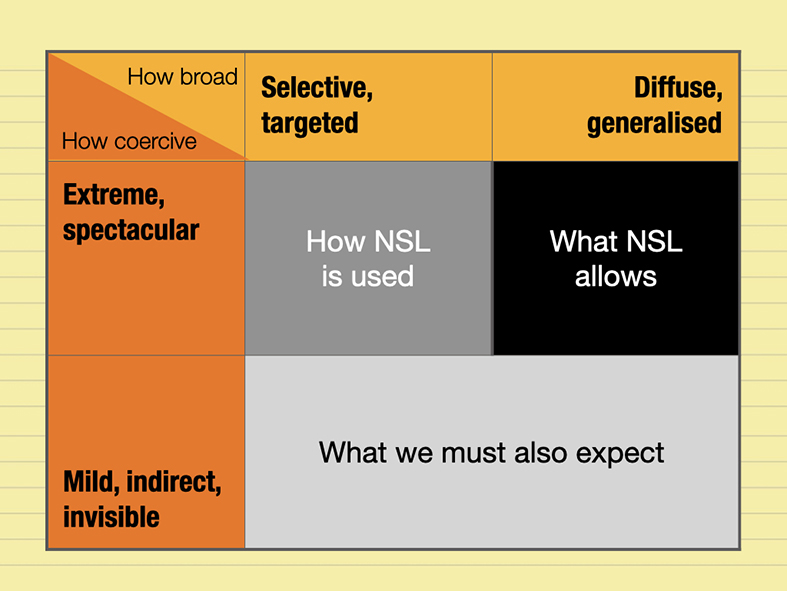

So censorship methods can be arrayed in a matrix like this:

While we should never underestimate the capacity or willingness of despots to use violence, it is equally unwise to underestimate their intelligence and sophistication.

They know that what often goes under the radar of media freedom monitors and the media themselves are economic carrots and sticks that are less violative of human rights but can be ultimately more damaging to the public’s right to receive.

In the late 2010s, Turkey was the world’s number one jailer of media workers – ahead of even China in absolute terms. But Turkish journalists will tell you that the regime has done even more damage to Turkey’s media independence through economic means. The government tamed two major newspapers in 2018 by pursuing their owner with tax evasion charges related to his non-media holdings. The publisher finally gave in, selling his media properties to a pro-Erdoğan corporation.

In the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte has used similar methods to attack the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the country’s largest newspaper. Under pressure, the owners sold the newspaper group in 2017 to a tycoon friendlier to the president.

One recent study found that journalists in the Philippines were more worried about economic and other stealth methods of control than about the arrests and other threats that attract international attention.

Despots sometimes want to draw attention to their coercion, to demonstrate their power. But they often prefer to control media out of sight. “Victimless” censorship can be the most effective: using invisible market forces to channel media energies in approved directions, without obvious violations of human rights.

Of course it’s not truly victimless – even if no media owners or media workers are hurt, the public loses. Remember, freedom of expression is not a right that belongs only to speakers. It is also includes the right to receive. So if it results in citizens not being able to partake of the full range of information and ideas they need for democratic self-government, censorship through the market is a rights issue.

Bringing Hong Kong into this picture, what obviously worries journalists about the NSL is that the letter of the law seems to allow for extreme and mass interventions, and turning all media into tools of patriotic education.

So far, though, the NSL has been used in a targeted way, mainly at the cost of Apple Daily. But this is only the first year, so media are understandably on tenterhooks, wondering if the authorities will use the NSL maximally.

What censorship studies tell us though is that we should also expect various other threats to media freedom, which while less spectacular may be more pernicious.

I should highlight in particular the administrative actions, not involving the NSL, that have already been taken to tame RTHK, Hong Kong’s public broadcaster – actions that have received a small fraction of the attention that Apple Daily has been given, but are arguably no less significant for the future of Hong Kong’s media environment.

In preparation for a webinar on media freedom post-NSL at my school last week, we put together a factsheet documenting incidents over the past year. It shows how wide is the array of threats media are subject to, many based on powers that pre-existed the NSL.

The NSL also has indirect effects. It is a powerful symbolic statement that emboldens radical pro-Beijing elements to harass and threaten liberal institutions and individuals outside of the legal arena. This is reminiscent of the effect of blasphemy law in many countries — it incites extremists to engage in acts of vigilante justice to protect the honour of their chosen creed.

The Singapore comparison

Finally, let me turn to Singapore. I don’t mean to brag, but I think my country is the world’s most advanced case of post-Orwellian authoritarianism.

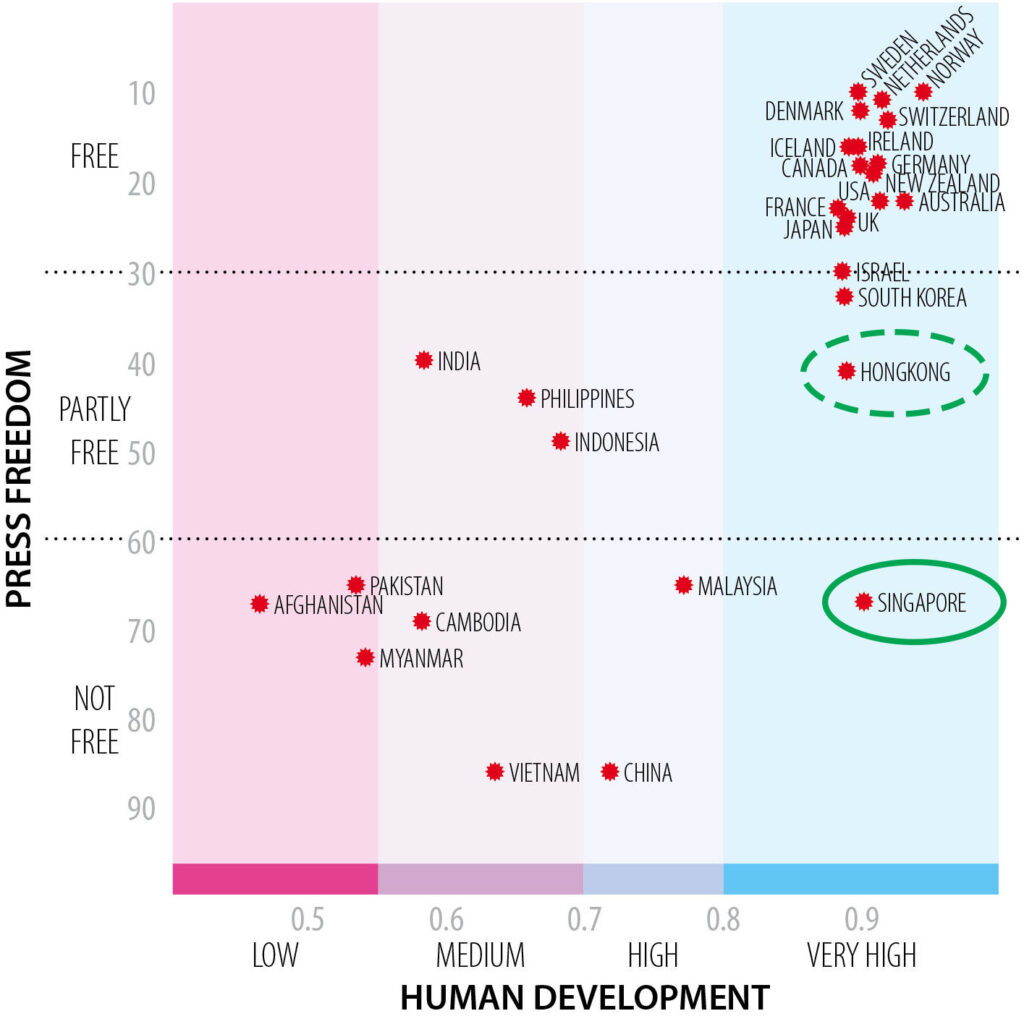

It’s not surprising that the country tends to pop up in these discussions about Hong Kong. It is an extreme outlier in data relating socio-economic development and media freedom.

So Singapore no doubt gives the government here hope that Hong Kong can similarly defy the West’s conventional wisdom.

So is Hong Kong heading Singapore’s way? I suspect that, yes, Hong Kong will be, like Singapore, a prominent outlier in charts that relate economic development with media freedom.

But I do not think that Hong Kong will be able to reach Singapore’s current condition.

What makes Singapore the pre-eminent post-Orwellian authoritarian state is not just that is unfree, with no investigative journalism of note — that’s nothing special — but that it is uniquely devoid of open resistance, and therefore very rarely requires coercive interventions by the state.

The substitution of direct and coercive censorship with self-censorship was achieved over decades. It required a scorched-earth strategy to remove once and for all any oppositional media in the 1960s and 70s. This was followed by new press laws that allowed behind the scenes intervention, and that guided the media towards economic targets. After which coercion was highly calibrated.

Hong Kong’s starting conditions are very different, in terms of political geography and history.

Singapore leaders are forced to be more in tune with public sentiment not only because Singaporeans have the vote, but also because of our small size. This is hard to believe, but wherever he is in Singapore, a minister would never be more than 50km away from any other part of the country. Hong Kong’s rulers are more insulated from their own mismanagement of any crisis, and therefore more likely to respond in a clumsy and uncalibrated manner.

Even with the NSL, the Hong Kong authorities still don’t have the discretionary licensing powers that the PAP inherited from the British. The ability to use licensing to control access to the media industry was, I think, the trump card that enabled the PAP to co-opt news media in the 1970s and 1980s.

Finally, there is a legitimacy gap. The PAP came to power in 1959 through universal suffrage, earning its status as the leading force of Singapore nationalism the hard way. Even if elections are not completely fair, they are free enough to continue conferring the PAP with sufficient political capital to spend on harsh measures.

Furthermore, PAP consolidated its performance legitimacy during the “tiger economy” decades of relatively easy growth in East Asia. It is now much harder for governments to persuade citizens to trade their freedoms for non-credible promises of social mobility, even in Singapore.

For all these reasons, I cannot see Hong Kong becoming the exceptional oasis of calm that Singapore is. Instead, Hong Kong probably faces continued cycles be arrests and other direct and coercive attacks on media freedom, interspersed with periods of sullen, brooding political inactivity — with the government usually having the upper hand, but never succeeding in neutralising resistance or stifling dissent. On its current trajectory, Hong Kong will be far messier and more contentious than Singapore, like the vast majority of semi-free, semi-closed media systems around the world.

More

“What Global Censorship Studies tell us about Hong Kong’s Media Future“, in Global Media Journal.

Panel discussion at HKBU: