Main image: A 2016 photo of children in Naroda Patiya, a Muslim neighbourhood in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, that bore the brunt of the massacre led by Hindu nationalist leaders. In 2012, a trial court gave a BJP minister a life sentence for orchestrating the attack. She was released on bail weeks after Modi became prime minister. – Photo by Cherian George

“Modi has never been able to live down his association with the 2002 pogrom. Not that he has tried to. For a significant section of his core constituency, the Gujarat pogrom was about finally teaching Muslims a lesson, a long-overdue turning of the tables against a dangerous minority.”

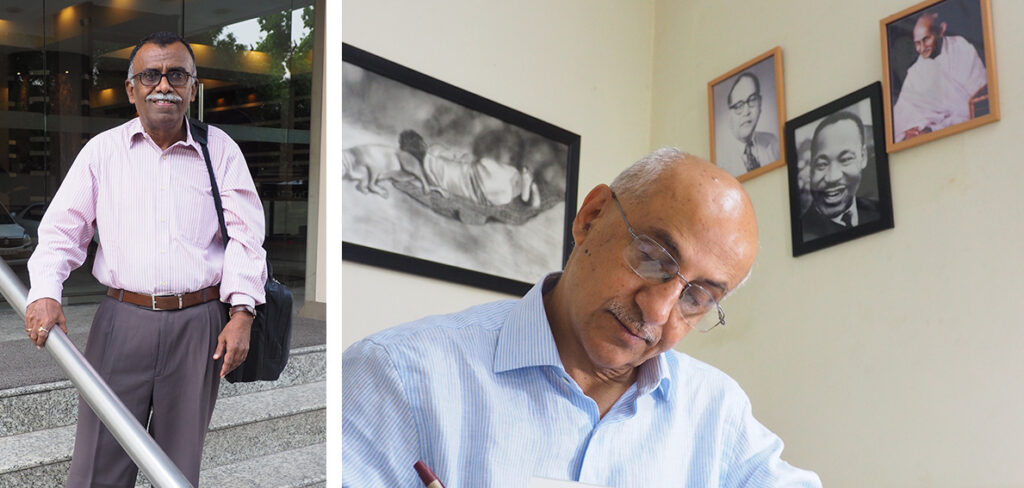

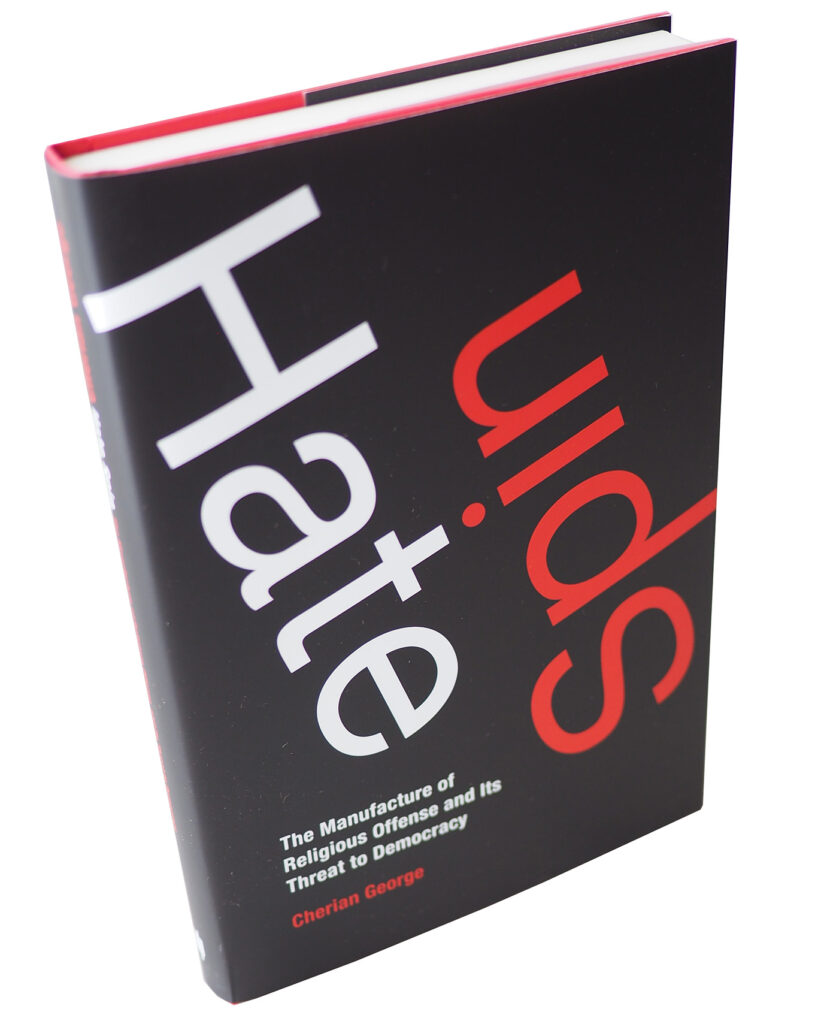

FEBRUARY 2022 — This month marks the 20th anniversary of the Gujarat Pogrom that Narendra Modi presided over as the state’s Chief Minister. This chapter from the 2016 book Hate Spin by CHERIAN GEORGE explains the event’s wider context and continuities. Hate Spin was named one the 100 Best Books of 2016 by Publishers’ Weekly.

On May 26, 2014, Narendra Modi was sworn in as India’s fifteenth prime minister. Government turnovers are nothing new in this constantly contested democracy. But the manner and meaning of Modi’s victory was revolutionary. Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won an outright majority of parliamentary seats—282 out of 543—without any help from the twenty-plus minor parties in the center-right National Democratic Alliance. In a country whose fractious diversity suggested the inevitability of coalition politics, this marked the first time in thirty years that a party’s right to govern did not depend on support from allies. With just forty-four seats, the Indian National Congress—the party of the founding fathers of the republic—had never found itself in a hole so deep or at such a loss for answers. Inspired by its Great Soul or “Mahatma,” Mohandas K. Gandhi, the Congress doctrine had always emphasized minority rights, especially for historically disadvantaged classes and castes, but also for religious minorities. India is the birthplace of more major religions—Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism—than any other civilization. Its Muslim population is larger than any other country’s save Indonesia and, perhaps, Pakistan.

Opposing the accommodationism of the Congress Party, the BJP aims to shift the political center of gravity decisively toward the four-in-five Indians who identify with the Hindu faith. Modi’s was not the first BJP-led government. But, in its previous stints, from 1996 to 2004, the BJP was restrained by the need to appease its coalition partners, resulting in a central government that was still recognizably Indian in its diversity. Modi’s term represented a radical break from the past, in that he came to the office with a strong majoritarian mandate. The 282 BJP Members of Parliament elected in 2014 included not a single Muslim. As a result of the BJP wave, the 543-member House included just 20 Muslims (less than 4 percent), in a country where Muslims account for around 14 percent of the population.

Modi did not land in office solely because of religion. By a factor of three to one, Indians believed that the BJP would do a better job than the incumbent Congress government in creating jobs, fighting corruption, and reining in inflation. Modi’s image as the man most likely to get India working again was the main factor behind his ultimate victory at the polls nationally. Even so, the BJP played the religious card assiduously in key states. Nor could Modi have emerged as the BJP’s unquestioned leader without brandishing his reputation as a Hindu chauvinist. He shot to prominence in 2002 as chief minister in the state of Gujarat, where under his watch perhaps a thousand Muslims were massacred, ostensibly in revenge for the burning of a train carrying Hindu pilgrims and activists.

WHISTLEBLOWERS R. B. Sreekumar and Harsh Mander. Sreekumar was head of intelligence of the Gujarat police when one pogrom claimed between one and two thousand lives. He handed over reams of evidence pointing to high-level political direction and police complicity in the riots. He revealed the uneven geographic distribution of fatalities. In places where honest law enforcers followed standard procedures for dealing with communal disturbances, few to zero deaths occurred, even in areas with a history of communal violence. Mander, a senior civil servant, also broke ranks to speak out. “This was not a spontaneous upsurge of mass anger. It was a carefully planned pogrom,” he wrote in a blog that was subsequently published in mainstream media. The idea that the Indian state lacks the capacity to suppress mass violence has no credibility, he says. “No riot can go on for more than a few hours without a complicit state. This was a state-sponsored massacre.” – Photos by Cherian George.

Politicians had used religion for electoral gain prior to Modi’s election. Despite its lofty ideals, the Congress Party was an early practitioner of what Indians call “communal” politics—dangerous, ethnic-based sectarianism. In 1984, Congress politicians instigated attacks on Sikhs to avenge the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. More than 2,700 Sikhs were killed. But, while others played occasionally with the fire of communalism, the BJP immersed itself in it and defined itself by it. Together with its allied movements, the BJP embraced hate spin as a key strategy. Indeed, in probably no other democracy today can one witness hate spin at work to the extent that it is practiced in Modi’s India.

Hate propaganda was an essential part of Narendra Modi’s rise to the leadership of the world’s largest democracy. His movement’s vilification of the Muslim minority through classic hate speech mobilized the far right and helped unite the caste-riven Hindu majority behind the upper-caste BJP. The Hindu Right also conducted a systematic campaign to manufacture extreme offendedness against historical writing perceived as defaming their religion. What is remarkable about the Indian case is not just the regularity of incitement and manufactured indignation. It is also the systemic, high-level use of this strategy that sets India apart.

The Rise of Hindu Nationalism

In Mahatma Gandhi’s fabled riverside ashram in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, is a poster recalling his stand against majoritarianism: “I do not believe in the doctrine of the greatest good of the greatest number. It means in its nakedness that in order to achieve the supposed good of fifty-one percent, the interest of forty-nine percent, may be, or rather should be sacrificed. It is a heartless doctrine and has done harm to humanity.”

SABARMATI ASHRAM in Ahmedabad. – Photo by Corey Seeman.

The quote reflects Gandhi’s conviction—shared with the architect of the Indian Constitution, the formidable Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar—that political life “was inconceivable without an unconditional equality in moral and social relations,” as the historian Aishwary Kumar puts it. India’s commitment to religious equality took on geopolitical significance after independence. Pakistan is the “other” of Indian nationalism, so it was important to demonstrate that Muslims who stayed behind in secular India instead of heading to Islamic Pakistan upon partition had made the right decision. However, the secular anticolonial nationalism of Congress was always challenged. The Muslim separatism that created Pakistan would continue to thrive in Kashmir. And there was Hindu nationalism. The same Gujarat that claims India’s greatest son would also produce Narendra Modi.

In the 1920s, Gandhi’s Ahmedabad was the spiritual center for the political principles of nonviolence and nondiscrimination. Eighty years later, Ahmedabad would be ground zero for one of India’s bloodiest communal massacres since partition. After that, in the new normal presided over by Chief Minister Modi, the city was divided by physical, institutional, and cultural walls completely antithetical to India’s founding vision. Muslims are ghettoized in the suburb of Juhapura, which is denied municipal services. “It is almost impossible for Ahmedabad’s Muslims to obtain a housing loan for a home in a Hindu area, and the city government of Ahmedabad has designated most of Juhapura as an agricultural zone. Muslims are therefore not only pushed on the margins of the city but also towards illegality,” says Zahir Janmohamad, an American human rights worker who witnessed the 2002 pogrom and has written a book about contemporary Ahmedabad.

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was formed in 1980. Like India’s other nationalisms, however, its roots go back to the late nineteenth century. The BJP is the political wing of a formidable network of groups referred to collectively as the Sangh Parivar (“family of organizations” in Hindi). The movement’s main driver is the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an all-male Hindu chauvinist organization founded in 1925. At its most benign, the RSS is a disciplined force of volunteers dedicated to social service, usually among the first to offer help in natural disasters. But RSS militants are also at the forefront of extreme intolerance, leading the charge in violence against minorities, organizing forced conversions, and attacking writers and artists.

EXPLAINING THE RSS: Pradip Jain. – Photo by Cherian George.

Pradip Jain, a smartly dressed lawyer, is the RSS spokesman in Gujarat. Sitting cross-legged on a divan in an office in Ahmedabad, he tells me that the role of the RSS is simply to spread good values and build good human beings, who would in turn build the nation. “Just like every family has a head, every society has a head, and religion is its head.” He explains that, while the country is ordered by its constitution, the nation is ruled by dharma, loosely translated as life-sustaining cosmic order. This is, he says, what sets India apart from other nations. “In India, dharma is supreme.”

This self-understanding, of being both separate from and superior to the trivialities of electoral politics, makes the RSS an uncompromisingly ideological organization. It has no political agenda as such, Jain insists: it inculcates values and does not interfere with the state. This, however, is not some isolationist sect. The RSS may not want to govern—that is the BJP’s job—but it obviously relishes power, and does not mind being feared. It has mastered its unique place in Indian life, everywhere and nowhere, fluid and iron. The RSS doesn’t even have a formal membership system, Jain says, but that does not stop him from giving a small, satisfied smile when I point out that it is reputedly the largest voluntary organization in the world. And even as he insists that the RSS does not tell its followers what to do, Jain notes that each is required to give back something to the society in his own sphere. “The person who has built his persona through Sangh will not leave any stone unturned,” Jain says with the same smile. You get the sense that the chill invoked by this choice of words was probably not accidental.

The RSS and its family of organizations are seized by the perceived threat to the status of India’s majority religion. And like other fascist groups throughout history, the Hindu Right believes that the best defense is a good offense. It projects a muscular Hinduism that would wrest India into a new era of glory if given power, and brooks no dissent from those—including Hindus of a more liberal persuasion—who stand in their way. Violence is meted out or instigated by members of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) and other extreme groups within the family of right-wing organizations.

The Sangh Parivar’s ideology is dubbed Hindutva (“Hinduness”), to distinguish it from Hinduism. The movement does not demand a theocratic state or any explicit embrace of Hinduism as the state religion. Hindutva is a national-cultural rather than a religious category, seen as synonymous with the idea of India. Indians of other faiths, including Muslims, should therefore have no trouble accepting Hindutva, according to the Sangh Parivar. If they choose not to, they must be traitors to the nation. The Sangh Parivar’s main grievance is that India’s Congress-architected secularism has been too accommodating to Muslims and other minorities. One major symbolic sticking point is the state’s recognition of Muslim personal law for marriage and inheritance, while other Indians are subject to a uniform civil code. The Sangh Parivar claims to seek formal equality, and wants to remove policies intended to protect minority rights. But the movement has a record of religious discrimination, even in distribution of disaster relief, as well as extreme intolerance backed by physical violence.

BABRI MOSQUE in the 19th century. The mosque was destroyed in 1992. – Photo by Samuel Bourne.

BJP-led coalitions had brief moments in power in 1996 and 1998, followed by a full five-year term from 1999. The demolition of a sixteenth-century mosque in Ayodhya in 1992 contributed to the BJP victory by energizing RSS members on the ground. The Babri Mosque had allegedly been erected on the site of an ancient Hindu temple believed to have marked the birthplace of Rama, an avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu and the hero of the epic Ramayana. In 1990, BJP president L. K. Advani embarked on a 10,000-kilometer journey across northern India to Ayodhya, where he said he would build a new temple. He and his entourage were arrested before they could do any damage. In December 1992, however, the authorities felt they had no choice but to step aside when up to 200,000 activists descended on the sacred site. Although the attackers were initially characterized as a frenzied mob, journalists later revealed that Sangh Parivar leaders coordinated the group and the attack. “Volunteers were trained, logistics painstakingly put in place and the assault on the disputed shrine launched using large surging crowds with volunteers skilled in demolishing structures embedded in it,” reported the Times of India.

The appeal of BJP to Indian voters has never been guaranteed because Hindus in India do not generally behave as a vote-bank—they have not traditionally voted as a unified bloc. Varghese K. George, the political editor of the Hindu—a national newspaper that, despite its name, is one of Indian journalism’s stoutest champions of secular democratic values—identifies three structural weaknesses in the Sangh Parivar that, historically at least, limited its electoral prospects. First was the tension between Hindu traditionalists focused on the transcendental and a middle class impatient for higher standards of living. Second, caste divisions within Hindu society limited the appeal of BJP elites among less privileged groups. Third, there was an uneasy balance of power between the dogmatic RSS and the electoral pragmatism of the BJP.

Narendra Modi provided an answer to all three dilemmas, George says. For a start, he bridged the traditional and the modern. With the Gujarat pogrom of 2002, the state’s chief minister had already established his credentials as an unflinching defender of the faithful. He would spend the next decade cultivating the second part of what one commentator called his “two-in-one package of rabid Hindutva and pro-reform smartness.” Modi aggressively pursued economic growth while championing largely symbolic religious causes, for instance, opposing the slaughter of cows. Hindutva 2.0, as George calls it, breaks from the past mainly in its embrace of neoliberalism. Under Modi, Gujarat resisted redistribution policies and embraced economic growth. “Going by Mr. Modi’s public pronouncements over several years, Hindutva 2.0 is a particular variant of neoliberalism that dovetails religious nationalism with economic progress,” he says.

The second problem, caste, had been the major obstacle to the BJP’s achieving power in India’s poorer states. Backward castes—such as the Dalits, traditionally treated as outcastes or untouchables—felt better represented by the national Bahujan Samaj Party and state-level organizations such as the left-leaning Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh. To woo them, Modi flaunted his own backward caste origins, significantly broadening his appeal. But to foster Hindu unity, it was also necessary for Modi to conjure up a common enemy. Muslims—already associated with Pakistan and global terrorism—readily served that purpose. Modi’s predecessors recognized this when they tore down the Ayodhya mosque. The Supreme Court banned building anything in its place, so the site remained a potent injustice symbol for cultivating fear and loathing of Muslims.

Modi was also able to transcend the RSS–BJP tension. As a member of RSS since the age of eight, his pedigree was unquestioned. The first BJP prime minister, Atal Behari Vajpayee, had tried to keep the extremist tendencies RSS at bay. Unable to stomach the 2002 pogrom in Gujarat, he had even tried to oust Modi as the state’s chief minister. But by then, Modi was already untouchable in Gujarat. In 2013–14, he contemptuously brushed aside his rivals within the BJP. He had emerged as the Sangh Parivar’s best hope for returning to power. “In the persona of the Gujarat chief minister—who projects a masculine Hindu pride while seeming to embrace a pragmatic economic philosophy and sporting a Movado watch, Bulgari spectacles, and Montblanc pens—the RSS may have found a way to resolve, or at least dissipate, the tensions between its ethos and the exigencies of contemporary political life,” noted the journalist Dinesh Narayan.

NARENDRA MODI‘s neoliberal reforms won fans within and outside India. — Photo by Valeriano Di Domenico / World Economic Forum.

If the BJP’s road to Delhi in 1998 was paved with the shattered stones of the Babri Mosque, its stunning return in 2014 detoured through the blood-soaked streets of Ahmedabad as well as the supportive boardrooms of major corporations. Within 150 days of Modi becoming chief minister of Gujarat, Hindu hard-liners there were massacring Muslims. An investigation into the riots by the Campaign Against Genocide—a network of civil society organizations that includes Hindu and other faith-based groups—found the state government “complicit and culpable at the highest level.” Modi has never been able to live down his association with the 2002 pogrom. Not that he has tried to. For a significant section of his core constituency, the Gujarat pogrom was about finally teaching Muslims a lesson, a long-overdue turning of the tables against a dangerous minority. Moderates in the Hindu population were horrified, but—as politicians around the world understand—moderates don’t make the most effective army for an election campaign. The troops whose enthusiasm Modi needed most were members of the RSS, which had founded the BJP in 1980. Only with their blessings could Modi achieve preeminence within the BJP. Even after he emerged as the clear front-runner, when prudence might have suggested that he position himself as a more moderate and inclusive PM-in-waiting, Modi’s campaign burnished his image as a Hindu strongman. The giving and taking of religious offense continued unabated.

Sectarianism and the Regulation of Offense

Before we examine how Modi and the BJP rolled out hate spin for the 2014 election, we should map India’s unique legal landscape. As I noted in earlier chapters, hate spin can be both constrained and facilitated by the law. India’s laws are a hybrid of its democratic commitment to freedom of expression and its instinct to protect the religious feelings of its citizens, a response conditioned by its history of sectarian conflict. The Indian Constitution and Supreme Court have always taken freedom of expression seriously, and its political culture prizes the right to dissent vociferously against governmental authority. It outperforms most of the Global South in political rights and civil liberties, and it is only one of five territories in Asia rated “free” by Freedom House. India is closer to the United States than to, say, Pakistan or Russia in the formal protection it offers to freedom of expression. At the same time, India deviates from liberal democratic norms in its desire to police offense. While the United States reacted to its legacy of sectarian conflict by developing an extreme allergy to state intervention in theological quarrels, Indian lawmakers adopted the opposite response, diving in to push apart contesting communities, refereeing their religious disputes, and creating no-go areas in what otherwise remained a colorfully contested public sphere.

Although contemporary commentators frequently speak of the Hindu–Muslim conflict as an almost timeless, ontological constant, historians of India generally consider it an outcome of British rule. Precolonial history was not free of violence, of course, but the colonial government’s administrative classifications and its policy of divide-and-rule had the effect of freezing previously fluid identities and making them more salient. Self-consciously sectarian conflict is therefore more recent, with Hindu–Muslim riots dating back only to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when there was growing competition between then-dominant Muslim elites within the colonial administration and the rising educated class of Hindus in northern India. Once the state recognized communally defined publics and accorded their representative organizations and leaders the status of legitimate interlocutors, they would develop a life of their own. Thereafter, when the nationalist leaders Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi tried to shape an all-encompassing Indian identity, they had to accept the political reality that the leaders of various religious and linguistic groups would insist on holding on to their own constituencies.

COLONIAL LEGACIES. Calcutta High Court, 1890s. Britain’s divide-and-rule strategy shaped post-independence politics.

Sectarian competition was tragically written into the narrative of independence. The crude, cruel partition into Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India led to the largest migration in history. The upheaval escalated into violent clashes, killing an estimated one million civilians. The trauma of partition, together with the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi by a Hindu extremist, gave urgency to the secularist project, but failed to inoculate India against future outbreaks of communal violence. Inter-religious riots have remained part of the soundtrack of the Indian story, mostly in the background as low-intensity conflicts, but occasionally erupting into mass violence. “India may be an officially secular state, but Indian society is defined by religious identities and riven by communal mistrust and hatreds,” notes Robert Hardgrave, a scholar of South Asian politics.

The Indian Constitution gives all citizens the right to freedom of speech and expression in Article 19(1)(a). However, Clause (2) allows restrictions “in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency, or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation, or incitement to an offence.” By democratic standards, notes the constitutional lawyer Bhairav Acharya, this is an exceptionally long list of permissible limitations. “We do not have a consistent or coherent free speech doctrine,” he says. The new republic retained colonial-era restrictions designed to keep order between communities. The Indian Penal Code has numerous sections curtailing freedom of expression that threatens the peaceful coexistence of religious groups. Under Section 153A, individuals can be fined or jailed up to three years for any attempt to promote “enmity between different groups on grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc., and doing acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony.”

Section 295A is the closest thing India has to a law against blasphemous libel. The colonial government devised it in 1927, in response to Muslim groups’ outrage over a controversial pamphlet on the life of Prophet Muhammad. The authorities had failed to secure the publisher’s conviction under the older Section 153A, which the judge said was “intended to prevent persons from making attacks on a particular community as it exists at the present time and was not meant to stop polemics against deceased religious leaders.” Within months, as Muslims’ anger continued unabated, Section 295A was introduced to plug the perceived gap in the Penal Code, covering “deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.” With that, says Acharya, the right to offend was taken away. “The idea that government must bow to street protest was born here,” he says. “This is not the right to give offense. This is expanding the right to take offense.” The outcome was the product, explains Acharya, of the colonial government’s hallmark impulse to maintain public order by keeping communities separate—a governance approach that carries on to this day. While the modern concept of defamation is meant to protect the reputation of individuals, India has grafted onto it “an inchoate and as yet undefined notion of community honor,” he adds.

Penal Code prohibitions against offense are also contained in Section 505(1)(c), which amounts to a group libel law dealing with statements, rumors, and reports that incite one class or community to commit any offense against any other class or community. Section 505(2) penalizes anyone who “makes, publishes, or circulates any statement or report containing rumour or alarming news” likely to create or promote “feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will” between different castes or communities. Most of these Penal Code offenses are punishable with jail terms of up to three years, with stiffer penalties if committed in a place of worship.

But despite the multilayered defenses against religious offense, India’s political system and culture cannot be characterized as thin-skinned. Indian political tradition embraces a long history of contestation between conservative and liberal impulses, and a multitude of positions in between and at either extreme. Even in 1927, when Indian legislators passed Section 295A, they were practicing what the historian Neeti Nair calls “legislative pragmatism.” Nair points out that while the colonial authorities felt compelled to prohibit religious insult, Indian lawmakers representing diverse interests and perspectives were under few illusions that this would solve the problem of communal conflict. Significantly, legislators entertained many proposed amendments to the bill to ensure that the new legislation would not punish sincere criticism of religion, calls for social reform, or historical research.

WINNING STRATEGY. BJP leader Amit Shah (left) Prime Minister Modi at the swearing-in of Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath and his government in 2017. India’s Election Commission has not been able to deter the use of hate speech in election campaigns. — Photo: PM’s Office.

Since independence, India’s higher courts have on many occasions thwarted the abuse of insult laws. Judges, recognizing the value of historical and artistic explorations of communal themes, have struck down attempts to censor expression deemed offensive. When one of the conspirators in the 1948 assassination of Mahatma Gandhi wrote a book explaining his actions, the Bombay High Court invalidated the government’s decision to confiscate all the copies. In its 1971 ruling, the court noted that the author was dealing with past history and not contemporary issues, and that the book should be assessed in its entirety and not solely on passages taken out of context. In 1988, the Supreme Court ruled that the instructional benefits of a television serial portraying religious extremism leading up to the partition of India outweighed its alleged inflammatory potential. Similarly, when authorities censored a documentary film on the 1984 massacre of Sikhs on the ground that it would stir communal tension, the Bombay High Court objected. In its 1997 ruling, the court said that the film’s message of peace deserved the protection of the Constitution’s free speech provision. In 2005, the Calcutta High Court rejected the state government’s arguments for confiscating a book decrying the plight of women in Muslim Bangladesh. The government had claimed that the book violated Section 295A of the Penal Code, as it would outrage religious feelings and insult the beliefs of Muslims in India. The court ruled, however, that the book should be read in the context of the struggle for women’s equality.

Surveying such rulings handed down by the Indian courts, some analysts place India near the positive end of the free speech spectrum. India’s laws, says one Western legal scholar, are not overly broad but narrowly tailored and “limited to seditious intentions, or words that promote ill-will between groups, and therefore do not suppress more speech than is necessary.” Such a conclusion seems to be based on the final outcomes of certain landmark cases that have wound their way through the system and resulted in progressive rulings by higher courts. Unlike in the United States, however these rulings have not been consolidated into clear and rigorous tests against which the constitutionality of free speech restrictions are to be judged. Furthermore, the justice system is tainted by corruption at the lower levels and overwhelmed with the sheer numbers of cases: at least 32 million cases are pending in the lower courts, with 56,000 pending before the Supreme Court.

Even if India’s courts ultimately tend toward protecting free speech, then, the old adage about justice delayed applies. Individuals who are gratuitously accused under India’s insult laws can be denied justice for a prolonged period. This makes insult laws a ready weapon for harassment and censorship, prone to abuse. “The process is the punishment,” says Geeta Seshu, a media freedom activist. One victim she tried to help was Shirin Dalvi, a Mumbai newspaper editor who was hounded for publishing a picture of the cover of Charlie Hebdo bearing a caricature of Prophet Muhammad to accompany a story about the killings in Paris. Dalvi was summoned to five different police stations where complaints had been lodged, Seshu says. A practicing Muslim, Dalvi clearly had no intention to cause offense. She apologized as soon as readers objected to the republication of the cover. Seshu was hopeful that the courts would eventually quash the charges, but the damage had already been done: Dalvi lost her job and was forced to go into hiding, due to threats of violence. Her newspaper had to close down and a career she had built over 20 years was in jeopardy.

The ease with which opportunists can game the legal system also explains the gap between election laws and election practice. The Election Commission has been criticized for its failure to regulate hate speech during campaigns, although, to be fair, the job may simply be too large for any institution to cope with. When it sees clear breaches, the Election Commission typically adopts a two-pronged response. Since such speech usually involves a statutory violation, it first lodges a complaint with the police to initiate criminal proceedings. In addition to the Penal Code, the commission may invoke the Representation of the People Act of 1951, which prohibits the practice of urging voters to choose on the grounds of “religion, race caste, community or language,” or influencing the vote through “the use of, or appeal to religious symbols.” Persons in violation of this act may be disqualified from running for or taking up a parliamentary seat. However, the process of charging and prosecuting offenders could take several years, and is partly at the mercy of uncooperative state governments.

In addition to filing police reports, therefore, the Election Commission independently serves notice that the candidate has violated the Model Code of Conduct. This second prong began as a voluntary mechanism, but it has been endorsed in Supreme Court pronouncements. The code leads with statements on communalism. “No party or candidate shall include in any activity which may aggravate existing differences or create mutual hatred or cause tension between different castes and communities, religious, or linguistic,” it says in its first paragraph. Point 3 of the code reads, “There shall be no appeal to caste or communal feelings for securing votes. Mosques, Churches, Temples, or other places of worship shall not be used as forum for election propaganda.”

Responding through the Model Code of Conduct has an immediacy that the Penal Code lacks, notes the former chief election commissioner of India, S. Y. Quraishi. Applying the code, the Election Commission can direct political parties not to field a candidate who has used communal speeches, or to impose a gag order on the candidate during the remainder of his or her campaign. The moral authority of the Election Commission is not negligible, since parties do not want to appear too irresponsible. One limitation of the Election Commission’s regulation of political activity is that it applies only to the period after elections are called. The Model Code of Conduct does cover election manifestos regardless of when they are released, on the ground that these are clearly intended for electoral purposes. But the Election Commission is powerless to regulate speeches and other communications in between polls—which is most of the time. The law has never been India’s only protection against sectarian politics.

India’s irreducible diversity provides another powerful check. In the past, major parties and candidates took it for granted that national leaders had to accommodate India’s diversity to hold power at the center. This had been the case with BJP’s previous tenure, under Prime Minister Vajpayee. Many party leaders interpreted its crushing defeat in 2009 as a rejection of its turn toward more a hard-line Hindu nationalist position. According to this conventional wisdom, a polarizing figure like Modi would be incapable of generating the kind of broad-based support that a national party needed. Congress leaders continued to make this claim as the 2014 polls approached, with rising desperation and diminishing credibility. Modi remained uncompromising. Instead of reaching out to minorities, he played the mathematics of the first-past-the-post electoral system, consolidating the BJP’s base and securing a decisive Hindu majoritarian verdict. His achievement required an ideological reframing of Indian secularism and democracy away from minority rights toward majoritarian power; away from Hindu eclecticism toward Hindutva fundamentalism. Hate spin was critical for this enterprise.

Hate Speech on the Road to 2014

It would be hard to find a hate spin factory that has been more systematic and productive than the Sangh Parivar. Its hate speech was not merely the result of loose cannons. Even when it appeared that its people were losing their heads, there was method to the madness. The Hindu Right cultivated anti-Muslim hate in order to marginalize, and in some cases even disenfranchise, members of the country’s largest religious minority. Perhaps even more importantly, the BJP understood that conjuring up a reviled out-group was the easiest way to unite a Hindu majority divided by caste, class, and language.

Key Themes in Hindutva Hate Speech

One illustrative case involved a Muslim-bashing video titled Bharat Ki Pukar (translated as “the call of India”). The BJP circulated this compact disc before the 2007 assembly elections in the key state of Uttar Pradesh. The video employed several well-worn hate speech motifs to depict Muslims as a threat to survival against which the BJP offered salvation. It opened with a voiceover of “Mother India” warning that the country was on the brink of ruin: “By using terrorists, spreading fear and dividing us, Pakistan wants to break India into pieces. … Now, ordinary people of India have to think, do they want slavery again or Ram Rajya in their independent India.”

“Ram Rajya” translates as the Kingdom of Ram. The BJP says that the term merely denotes good governance, but in the context of an election campaign, it is a thinly disguised emotive Hindutva clarion call. The video also included such lines as, “The other parties, they are all agents of the Muslims.” The impending Muslim takeover, the video threatened, would mean the closure of all schools and colleges. “What will open are madrasas from where fatwas will be issued to drive Hindus out from this country, enslave them—because they want to rule over here, they want to make India into Pakistan.”

GEETA WEEPS: A scene from the hate propaganda film Bharat Ki Pukar.

The video featured various portrayals of Muslim subterfuge. In one scene, a Muslim man (identified by his skullcap) plants a bomb under a car. Another vignette showed the two sons of a Muslim butcher concealing their identities to trick a Hindu farmer into selling them his cow. A fifty-second-long clip of a buffalo being slaughtered follows. The theme of Muslim deceit continued with the story of a young man who lures a Hindu girl away from her home before revealing his true identity as a Muslim. He gives her to an older man, to be wed. She is dragged away screaming, as her husband-to-be laughs, “When Hindu girls get ensnared by us, they scream and shout but sadly there is no one to listen to them and we have great fun.” A later scene showed a Muslim woman declaring it her duty to produce more children. This was followed by what looked like a news clip, in which a Hindu woman said: “Hindus will produce two children and Muslims will marry five times and produce thirty-five pups and make this country into an Islamic state.” Near the end of the video, a Hindu social worker urged viewers to mount a new independence struggle and “take an oath to drive those traitors out of the country.” The video ends with images of the BJP flag, party leaders, the Babri Mosque being demolished, and so on.

The tropes contained in Bharat Ki Pukar were repeated in the 2014 general election campaign. BJP propaganda equates its Muslim opponents with traitorous Pakistanis whose terrorist acts threaten national security. It is not just high-profile, big-city targets that are supposedly at risk. At the village level, Muslims violate the sanctity of cows and the honor of women. Without the BJP’s leadership, Muslims would overwhelm Hindus by being more duplicitous and more fecund, voters are told.

The fact that none of this is true is immaterial to the Hindu Right. Consider the claims about Muslim men, their several wives and multitudes of children. There is no evidence that, controlling for income, Muslims have a higher fertility rate than Hindus. The Sangh Parivar’s followers nevertheless believe that Muslims, currently 14 percent of the Indian population, are to be feared as a would-be dominant majority. A people renowned for its mathematical prowess thus indulged in creative arithmetic license, concluding that Hindus would become a minority in their own country. If the Sangh Parivar could get away with such fictions, they could perhaps get away with anything. Hence the “love jihad.”

Love Jihad and the Muzaffarnagar Riots

The “love jihad” is a bizarre myth about a Muslim campaign to conquer Hindus by stealing their girls, one heart at a time. The story goes that a handsome young man appears in the community and woos away a Hindu girl with his seductive charms and promises of a better life. He has been schooled in a madrassah, but possesses the wherewithal for modern courtship, like a motorcycle and a mobile phone. Only after she has run off with him does he reveal himself as a Muslim, either forcing her to convert or selling her off into slavery.

Like all good propaganda, there is a molehill of fact somewhere within this mountain of fiction. Love often does blossom between young men and women whose matches are deemed unsuitable. Sheer probability dictates that most of these scandalous liaisons involve Hindu couples of different castes or classes; relatively few are interreligious. Some of the couples elope; some are forcibly, even fatally, separated—including through the infamous practice of “honor killings.” India does also suffer from the entirely separate problem of human trafficking. One ploy of the modern slave trade in South Asia involves con men appearing before the parents of eligible daughters, proposing marriage with substantial dowries, and then turning over their new brides to brothels in the big cities or the Gulf States. As for the mobile phone, the association with Muslims may ring true, for mobile shops in some parts of the country are owned mainly by landless Muslim men (who, through such enterprise, may also accumulate enough savings to buy motorbikes).

CONSPIRACY THEORY: A love jihad poster.

It is apparently easier to blame a mythical love jihad conspiracy than to confront uglier truths—that the obsession with social status sometimes turns young romance into needless tragedy; or that poverty and ignorance makes families easy prey for dowry-bearing human traffickers. Whatever the social psychology behind it, the myth of love jihad became a widely held belief ripe for electoral exploitation in the run-up to the 2014 election. BJP operatives played an active role in its cultivation.

One simple tactic in promoting the myth was to print posters and newspaper advertisements listing a hotline number to call if you feared that a family member might be a victim of a love jihadist. The ads depicted a handsome, bearded young man riding a motorcycle, with a happy girl behind him. Its creativity and simplicity would do any ad agency proud. Instead of trying to prove the existence of a disease, it advertised the cure. The underlying message: if the people in authority need to launch a hotline, there must be a genuine social problem. Since the group behind the ad campaign wasn’t expecting any phone calls, they didn’t need to spend money to engage an Infosys call center; just a man with one phone line, if at all, would do.

The love jihad legend was not just some trivial sideshow in one of the world’s most entertaining electoral contests. It played a role in the BJP’s most important victory—the campaign for Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state. If it were a country, Uttar Pradesh’s 200 million people would compete with Brazil as the fifth most populous in the world; it accounts for 80 out of 543 seats in the Indian parliament. The dilemma for the BJP was that half the state’s population identified with so-called backward castes, which solidly backed two other parties, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Samajwadi Party. In the 2007 state assembly elections, these two parties won more than 303 out of 403 seats, with the BJP securing only 51. To win the general election, the BJP would need to win over the backward castes and unify the Hindu vote. It could not shed its upper-caste image, but it could present itself as the only force capable of protecting Hindus against a Muslim threat. The Bharat Ki Pukar video may not have done the trick in 2007, but the strategy would be refined and repeated in the coming years.

In mid-2013, Narendra Modi dispatched one of his closest associates, Amit Shah, to take charge of the BJP’s campaign in Uttar Pradesh. Shortly thereafter, in September 2013, communal riots erupted between Muslims and land-owning Hindu Jats in the district of Muzaffarnagar. Fifty-two people were killed and at least fifty thousand Muslims were forced to flee their homes in the country’s worst communal riots in a decade. The trigger event was a fight in Kawal village, allegedly over the harassment of a girl, though it could also have been over a motorcycle accident. In any case, three youths died, one Muslim and two Jats. Kawal at the time had a reputation as a “harmonious and business-friendly” village, where Muslims and Hindus lived apart but in economic codependence. Ordinarily, the fracas would have fizzled out, but provocateurs seized upon the incident. Everything from that point on bore the hallmarks of the engineered mass violence that is part of the rhythm of Indian politics. A crowd of thousands turned up for the cremation of the two Jat youths, after which they entered the Muslim colony of Kawal on tractors and motorbikes, looting and vandalizing Muslim houses and shops. The mob shouted such slogans as “Jao Pakistan, warna Kabristan” (go to Pakistan or the graveyard).

Within days, a video was circulating among Hindus, showing two men being beaten to death by a Muslim mob. Although later revealed to be a two-year-old recording from Pakistan, it was passed off as a video of the killing of the two Jat youth. Jat leaders called a major rally on September 7. Some 150,000 people attended, led by politicians and activists from Uttar Pradesh and neighboring states.

Several days of violence followed. Although a district magistrate in Muzaffarnagar ordered politicians to stay away, the temptation proved irresistible for the BJP. Several politicians were charged with inciting the violence, and one BJP parliamentarian was charged with uploading the fake video. A Frontline investigative report found that the love jihad conspiracy theory had been installed as a major plank in the BJP platform in rural Uttar Pradesh. Jats interviewed after the riots claimed that they needed to save the honor of their daughters and sisters. A Sangh Parivar leader said in a press statement that the riots came about because society “could no longer bear the ‘love jehadists’ outraging the modesty and dignity of Hindu women and girls” in Uttar Pradesh. An independent fact-finding team that visited the area two months later found Jats convinced that Muslims were determined to reduce Hindus to a minority in their country. “It was remarkable that these comments were repeated in almost the same words by all the Jats we met irrespective of the distance that separated their villages. This is probably indicative of a well-organized campaign over a period of time towards communalizing the atmosphere in the entire area,” the report said.

The next step for the BJP was to turn the events of Muzaffarnagar into a defining moment for its election campaign—just as Modi had done with the Gujarat pogrom through his Hindu pride tour ahead of 2002 state elections. Amit Shah arranged for some 450 minivans to traverse Uttar Pradesh with Modi’s message in pictures, video, and music, as well as a network of local workers organized along the lines of consumer marketing companies’ outreach to rural communities. In one rally, Shah said that the elections were about “revenge” and “honour”: “This election is about voting out the government that protects and gives compensation to those who killed Jats.” The statement betrayed cynical disregard for the fact that Muslim deaths outnumbered Hindu death by more than two to one, and that most of the resulting refugees were Muslim, many of whom were made to sign agreements not to return to their homes in return for financial aid.

The Election Commission took the unprecedented step of banning Shah from campaigning in the state for violating the Model Code of Conduct. But when Shah promised to abide by the Code and not use “abusive or derogatory language,” the ban was lifted. To former chief election commissioner S. Y. Quraishi, the commission’s action and the politician’s reasonable response demonstrates the moral authority of the Model Code. Unfortunately, as Quraishi acknowledged, Shah soon reverted to similar language. Uttar Pradesh responded by giving the BJP its sweetest victory. Of the BJP’s net gain of 166 seats in the general election, more than one-third came from the state. Modi handsomely rewarded Shah’s stewardship after the election, installing the forty-nine-year-old as the president of the BJP.

The Modi Touch

Throughout the 2014 election campaign, Modi’s surrogates continued to spew hate. In the state of Bihar, for example, BJP leader Giriraj Singh was censured by the Election Commission for “highly inflammatory” remarks involving cow slaughter. He also said that people opposed to Modi were “Pakistan-parasht” (pro-Pakistan) and should head there. Singh won his parliamentary seat and resumed his rhetoric of hate.

The most recalcitrant purveyor of hate speech among Sangh Parivar leaders was Praveen Togadia, international president of the Vishva Hindu Parishad. Undeterred by repeated criminal charges going back more than a decade, Togadia again showed his contempt for law and morality. He advised a neighborhood gathering of the various ways they could evict a Muslim businessman who had recently bought a house in a Hindu area in Gujarat, and how they could prevent such sales in the future. Just as Muslims were fighting the army in Kashmir, he said, “Where we have a majority, we should be brave enough to take the law into our hands and frighten them.” Modi waited a few days before chiding Togadia, with whom he had fallen out several years earlier: “I disapprove any such irresponsible statement & appeal to those making them to kindly refrain from doing so. Petty statements by those claiming to be BJP’s well-wishers are deviating the campaign from the issues of development & good governance,” he tweeted. Notably, his statement made no reference to the gravity of Togadia’s hate speech against minorities. His main grievance seemed to be that it distracted from the BJP’s current messaging.

In the final week of the campaign, on May 5, Modi appeared at a rally in the Uttar Pradesh district of Faizabad, adjacent to Ayodhya. Behind the podium was a giant portrait of Lord Rama. Its strategic placement ensured that every television camera trained on Modi would also capture Rama’s beatific visage hovering behind him. “Faizabad should allow the lotus to bloom in the land of Shri Ram,” Modi said. Although he did not refer to the controversial Rama temple project, the backdrop also carried an image of a temple. Other speakers, including the candidate for the area Lalu Singh, promised that the BJP would build the temple in Ayodhya. As the candidate, Singh was served notice for violating the ban on religious symbols contained in the Model Code of Conduct. Given that the campaign period was drawing to a close, Singh treated the admonishment lightly, remarking that he would seek legal advice.

While hate speech and communal appeals are nothing new in Indian politics, the BJP’s brazen contempt for the rules in the 2014 campaign was striking. Politicians, including Modi, openly dared the authorities to take action against them. One commentator likened the Election Commission to “an old schoolmaster who keeps ranting while kids continue with their pranks.” While the institution enjoyed wide latitude, its emphasis on due process allowed appeals and counteraccusations to stall its work.

Unscrupulous politicians also know that the commission’s findings are no match for the verdict of public opinion—in an election, nothing succeeds like success. BJP strategists were willing to write off any loss of support among Indians—Hindus as well as minorities—who agreed with the Election Commission that the party’s use of hate speech was unacceptable. The party probably made the simple electoral calculation that the gains from chauvinistic appeals, especially in Uttar Pradesh, would outweigh the loss of minority and liberal votes. The latter could be mitigated by emphasizing Modi’s economic agenda. Indeed, many Muslims were prepared to support him for that reason. Crucially, around 2010, India’s powerful business groups and the media they owned were giving up on the Congress Party and were beginning to turn to Modi as their next great hope. Bequeathed with both funds and media support, the RSS and the BJP were brimming with confidence.

The peculiar logic of polarized sectarian politics enables a kind of rhetorical alchemy: what appears to neutral observers as setbacks and embarrassments are magically transformed into strengths in the eyes of the party faithful. Thus, BJP politicians routinely cited the Election Commission’s interventions as evidence of a secular system that was intent on unfairly obstructing the true will of the people. Criticism by liberal journalists and academics helped cast the BJP as victims of a political conspiracy. The fiercer the opposition to the BJP, the more obvious it appeared to its constituency that it needed an uncompromising strongman like Modi.

The Battleground of History

The Sangh Parivar’s politics of intolerance and exclusion, most clearly manifested in its rampant use of hate speech in the run-up to the 2014 polls, have been pursued with equal resolve through a parallel campaign away from the electoral process. Instead of focusing on contemporary themes like terrorists from Pakistan or the love jihadi down the street, the propaganda in this campaign touts heroes and villains from centuries and millennia past. Its goal is to rewrite Indian history to match Hindutva ideology.

Of course, every open society debates its past in the light of current ideological battles. What is striking about the Sangh Parivar, though, is the force with which it has attempted to impose its own version of Indian history. Unable to win arguments on the basis of historical facts, the movement simply asserts the inviolability of Hindu feelings. While hate speech is the stock in trade of the Sangh Parivar’s rabble-rousing politicians, its assault on history relies on offense-taking. Evidence-based historical research is no match for enraged mobs, especially when these mobs are supported by laws designed to protect their sensibilities. Thus, tantrums triumph over truth.

The campaign’s point man is Dinanath Batra, the head of the educational arm of the RSS. Since the BJP’s 2014 victory, Batra, who had previously been entrusted with the task of revising history textbooks when the BJP first came to power in 1999, has been in ascendance once again. The rewriting of India’s history has become a major Hindutva priority, notes Amartya Sen, because it serves “the dual purpose of playing a role in providing a common basis for the diverse memberships of the Sangh Parivar, and of helping to get fresh recruits to Hindu political activism, especially from the diaspora.” Promoting cultural pride in Hindu identity is an important way to appeal to the majority of Hindus who are not necessarily hard-core supporters of the Sangh Parivar, he adds.

Myths Versus History

Romila Thapar, one of the world’s most distinguished historians of India, is all too familiar with the Sangh Parivar’s mission and methods. She was one of a handful of historians whose textbooks were attacked in the 1970s. In 2003, when she was given a chair at the US Library of Congress, her appointment was pilloried by Hindutva supporters who labeled her as Marxist and anti-Indian. Now an emeritus professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, Thapar continues to speak up for academic freedom and against censorship of academic history.

UNDER SIEGE: Historian Romila Thapar. – Photo by Cherian George.

Over tea in her Delhi home, Thapar elaborates on the centrality of history to the Hindutva project. First, the idea of India as a Hindu homeland and of Hindus as the primary citizens of India requires unquestioned acceptance of a simplistic periodization of Indian history—one that harks back to a golden age of Hinduism as the inspiration for the India of today. The Hindu period is supposed to have been followed by the dark age of Muslim rule, brought by invaders from outside India, and then British colonialism. Ironically, Hindutva periodization is based on colonial historiography—except that in the British version, colonialism marks the high point of Indian history.

“The ‘Hindu period’ and the ‘Muslim period’—we never had that kind of periodization in any historical writing prior to the coming of the British,” she tells me. “And to say that there was constant antagonism between the two without investigating the reasons for either antagonism or peaceful coexistence, as the case may be, is not exactly a historical approach.” In challenging colonial interpretations of India’s past and showing that their ethnic and religious categorization was a construct in support of colonial policy, modern historians like Thapar were also undercutting both religious nationalisms. “If you make a proper historical analysis, then in effect both Hindu and Muslim nationalism are weakened; they don’t have a historical basis for cultivating hostile identities or making religion the prime cause of all activity.”

Accordingly, Hindutva supporters take offense when historians point out, for example, that caste antagonisms have been at least as important as interreligious divides to India’s history. This was one of the inconvenient truths that got Thapar’s textbook censored: she had said that the shudras, a subordinate caste, were not treated well by the upper castes. Critics felt that she had failed to highlight the subjugation of Hindus by Muslims in the medieval period.

Second, Hindutva history involves a kind of streamlining to render Hinduism more amenable to political mobilization. “Hinduism in practice and belief was essentially the juxtaposition of multiple sects—where you could choose your deity, your form of worship, decide which temple you want to go to, decide the language of worship, and so on,” Thapar notes. Hinduism was organized very differently from Christianity in Europe or Islam in the Middle East, in that these other faiths could refer to a historical founder, a single sacred book, and hierarchical religious institutions. “That did not happen in Hinduism. Anyone is free to teach and create his own sect. And if he has a following, he has a following. And this has been going on right through the subcontinent with its uncountable sects,” she points out.

When Hindu nationalists needed to galvanize Hindus across the sub-continent, she says, they found it useful to adopt some of the features of the Judeo-Christian tradition that were amenable to mobilization. Since Hinduism lacks a historical founder, Hindutva ideology elevates the heroic figure of Lord Rama to preeminent status in the Hindu pantheon, based on dubious scriptural evidence. Claiming Ayodhya as his birthplace serves this larger purpose. And although there is no single sacred book in Hinduism, the BJP has floated the idea of according that status to the Bhagavad Gita; it was probably no coincidence that Modi presented a copy to Barack Obama at the White House.

Cow protection—a movement with origins in the religious nationalism of the late nineteenth century—can be read as another attempt to fundamentalize Hinduism. The movement has recently experienced a resurgence, with more states extending their bans on cow slaughter. Pure Hindus, the Hindutva movement needs to say, would never kill cows. Therefore, statements that Aryans of the Vedic period consumed beef—as stated in Thapar’s censored 1970s textbook—would have to be condemned as almost blasphemous. Proponents of Hindutva mythology prefer nineteenth-century Orientalist scholarship that plants the roots of Hindu identity in the glorious Vedic civilization of some three thousand years ago, when the Vedas, the oldest Hindu scriptures, were composed. The political need to refer to a pure tradition explains why Hindutva supporters take offense when research about their supposed golden age does not conform to their idealized picture of it.

This zealous streamlining of Hinduism’s internal diversity provides simple ideas and symbols around which Hindu support can rally. An especially shrewd aspect of the Hindutva movement is that by defining itself as a national ideology, Hinduness, it does not actually need to reform Hinduism, or require that Hindus change their practices or pledge allegiance to one religious leader over another. There is still no pope or ayatollah; Hindutva does not require the head of state to be the head of the faith. When we recall how much blood has been spilled in power struggles within world religions—between Catholic and Protestant, Sunni and Shia—we begin to appreciate the genius of Hindutva mobilization. It focuses on presenting a unified symbolic front against external threats while continuing to allow diversity to flourish within.

Attacks on Academic History

During the BJP’s first stint in power, the American academic James Laine’s Shivaji: The Hindu King in Muslim India became a target. First published in New York, it was released in India by the New Delhi branch of Oxford University Press in 2003. Shivaji, the subject of Laine’s study, was a famous seventeenth-century warrior who carved out a Maratha kingdom during the Mughal period. Laine’s biography was critical of how the story of a cultural hero was later appropriated and reshaped by those seeking a symbol of Hindu strength standing up to Muslim invaders. The book included the widely accepted fact that Shivaji was greatly influenced by his mother, and mentioned contemporary rumors, such as the following: “The repressed awareness that Shivaji had an absentee father is also revealed by the fact that Maharashtrians tell jokes naughtily suggesting that his guardian Dadaji Konddev was his biological father.”

Although Laine did not claim that these stories were true, a group of Indian scholars asked the publisher to withdraw the book, claiming that it had cast baseless aspersions on Shivaji. Oxford University Press (India) expressed regret for the offending statement and instructed all its Indian offices to withdraw all copies of the book from circulation immediately.

The proverbial train, however, had left the station. The following month, in December 2003, Shiv Sena, a far-right political party in the state of Maharashtra, sprang into action. Its thugs attacked a professor of Sanskrit whom Laine had thanked in his acknowledgments. The following day, Shiv Sena visited the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) in Pune for the same reason, but left without harming anyone. In early January 2004, however, another right-wing Maratha group, the Sambhaji Brigade, attacked BORI. The goons ransacked the library, destroying thousands of books and priceless manuscripts. Ten days later, Maharashtra banned the book under Section 95 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

The state also filed a complaint (in the form of a First Information Report) against Laine, the publisher, and the printer for allegedly breaching various sections of the Penal Code, including Section 153A. Police arrested one of the owners of the printing press. At first, Prime Minister Vajpayee criticized the ban. By March, however, with elections looming, the prime minister climbed aboard the bandwagon, saying that Laine’s experience should serve as a warning to foreigners not to take liberties with India’s national pride. According to court documents, the Bombay High Court suggested a pragmatic resolution: the author might wish to withdraw the allegedly objectionable portion from his book, simply to put an end to the controversy. Laine, in the meantime, had already faxed an apology after the attack on the Sanskrit professor, and expressed his anguish at the incident in a subsequent interview. He may have agreed to compromise, but the Maharashtra government demurred.

The case finally ended up in the Indian Supreme Court, which quashed the criminal proceedings in April 2007. It invoked a principle that had been set out in a 1997 case: since Section 153A refers to friction “between different” groups, it requires that at least two communities be involved. Merely upsetting one group without reference to another cannot be a violation of that section. Furthermore, the intentions of the author, the intended audience, and the context of the expression had to be taken into account. The court was satisfied that Laine was engaged in “purely a scholarly pursuit.” It said, “One cannot rely on strongly worded and isolated passages for proving the charge nor indeed can one take a sentence here and a sentence there and connect them by a meticulous process of inferential reasoning.” The Bombay High Court duly lifted the book ban in 2007. The Supreme Court turned down an appeal from Maharashtra in July 2010, stating that the ban could not stand since the case against Laine had already been quashed.

What should have been a victory for intellectual freedom had a hollow ring. The Supreme Court ruling did not diminish the Sangh Parivar’s desire to sterilize its ideological environment. Nor did it stiffen the resolve of book publishers or academic institutions to publish works that might offend members of the Hindu Right.

In parallel with the assault on Laine’s Shivaji, the Sangh Parivar rolled out a scandalously successful campaign to get the University of Delhi to censor an eminent literary scholar’s essay on the Ramayana. A. K. Ramanujan’s article “Three Hundred Ramayanas” highlighted the existence of various versions of the Ramayana. The article has been widely recognized as the work of a great lover of the epic. His translations had done much to win Indian mythology new admirers in the English-speaking world.

The essay was added to the reading list of a Delhi University course in 2005. Complaints started surfacing in 2008. When the university stood firm, activists entered the history department head’s office, vandalized it, and roughed him up. A group headed by Batra filed a civil suit, as a result of which in 2010 the Supreme Court directed the university to form an expert committee to study the matter and make a recommendation to its Academic Council. Of the four historians appointed to the committee, three endorsed Ramanujan’s scholarship and saw nothing controversial about the article. Nevertheless, the Academic Council decided in late 2011 that the essay be dropped from the reading list.

The previous year, ruling on the Shivaji case, the Supreme Court had said that a publication’s impact had to be judged by the “standards of reasonable, strong-minded, firm and courageous men, and not those of weak and vacillating minds, nor of those who scent danger in every hostile point of view.” This appeared to make no impression on the academics, who agreed with the lone expert on the review committee that a combination of ill-equipped teachers and impressionable minds meant that the essay could cause offense. Celebrating the censorship of the article—written by a fellow Hindu, it should be noted—Batra said: “It was a conspiracy hatched on the part of Christian Missionaries and their fellow travellers to demean our gods and goddesses. It has been thrashed.” Supporters would be mobilized to keep a close watch over the university syllabus, he added.

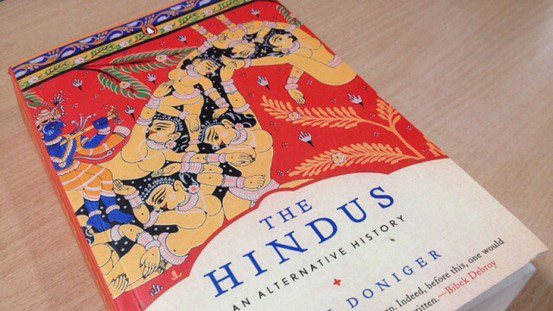

Around the same time, another challenge to academic freedom was working its way through the legal system. In February 2010, Batra initiated legal action against the American academic Wendy Doniger over her book The Hindus: An Alternative History. The book was first published in the United States by Viking Penguin in 2009 and then released by Penguin India in 2010. Batra claimed that the book was “a shallow, distorted and non-serious presentation of Hinduism,” “riddled with heresies and factual inaccuracies,” and highly offensive.

MANUFACTURED INDIGNATION: Censored in India.

Doniger, a professor of the history of religions at the University of Chicago Divinity School, made claims—for instance, that the Ramayana is a work of fiction—that were within the mainstream of Indian scholarship. Opponents, however, claimed the work to be hurtful to the feelings of millions of Hindus. Writing in the New York Times, Pankaj Mishra noted that fanatics would correctly perceive Doniger’s focus on “the fluid existential identities and commodious metaphysic of practiced Indian religion as a threat to their project of a culturally homogeneous and militant nation-state.”

The campaign against Doniger’s book presents a reality check to well-meaning liberals who believe that showing more respect for religion would appease offense-takers. Batra’s original lawsuit alleged, among other things, that the book defames the revered nineteenth-century Hindu monk Swami Vivekananda by saying that he had asked for beef. Doniger has pointed out that Batra did not claim that the passage is false, since it is well documented.

“The objection is simply that repeating that statement in the book defamed Vivekananda,” she explained. Their quarrel, therefore, was not over the need for civility—at least, as this virtue is understood in a secular society. Instead, Batra appeared to be claiming that scholars had no business interpreting religious traditions and texts.

Penguin India fought the case for four years before approaching Batra for a settlement. In early 2014, it agreed to cease publication and promised to pulp all remaining copies, although this proved unnecessary as the book had sold out. Penguin said it stood by its original decision to publish The Hindus, but claimed that Section 295A of the Penal Code made it “increasingly difficult for any Indian publisher to uphold international standards of free expression without deliberately placing itself outside the law.” In a New York Review of Books essay, Doniger echoed her publisher’s position that India’s overbroad laws were to blame. With the wrong judge, you could be convicted under these laws, she opined. “It’s hard to imagine how you could write about any subject as sensitive as religion or history without outraging someone; such a rule would mean the end of creative and original scholarly thought,” she said. “Any new idea offends people who are committed to the old idea, which is to say, most people. Even in the hands of someone as intellectually challenged as Batra, Article 295A is a weapon of mass cultural destruction.”

Many liberals were not as charitable toward Penguin, criticizing it for cowardice. Lawrence Liang of the Bangalore-based Alternative Law Forum issued a legal notice, dripping with sarcasm, stating that since Penguin was “mutating into a chicken” and not interested in exercising its rights as owners of the work, it should allow anyone else to copy, reproduce, and circulate it in India. In a commentary in Frontline, the prominent historian and lawyer A. G. Noorani said the publisher and the author were “wildly wrong” to think that the courts would have ruled against them. There was no precedent of a historical work like Doniger’s being suppressed either under Section 295A or through a civil suit, Noorani explained. Batra had won “by simply brandishing a toy gun.” In Noorani’s eyes, Penguin Books India preempted justice when it surrendered to Batra.

There is, of course, a more straightforward explanation of Penguin’s behavior. Penguin admitted defeat not because it misunderstood the letter and spirit of the law, but because it correctly appraised the sorry state of India’s rule of law. Regardless of what the courts decided, the publisher would have to deal with street justice. It had “a moral responsibility to protect our employees against threats and harassment where we can,” Penguin said.

Pratap Bahnu Mehta, a social scientist who heads the distinguished Centre for Policy Research in Delhi, fears that the vitality of Hindu piety is being overwhelmed by an invented communal identity focused on a history of oppression. “It is an identity constituted by a sense of injury, a sense of always having been on the losing side, of being a victimized innocent.” For the Hindutva movement, though, the revising of history is long overdue. Gujarat’s RSS spokesman, Pradip Jain, says independent India must make up for the lost years of the “in-between period” when Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru allowed its glorious past to be diluted. They had acted like the new owners of a house who, upon moving in, inexplicably allow the previous owner’s décor to remain intact, complete with photos of his ancestors. “I would replace it with my own grandfather’s pictures,” says Jain.

A Year Later

Faced with the realities of governing, candidates who campaign as extremists often become moderates in power. But two years after Modi’s arrival in Delhi, there are few signs of moderation in Hindutva hate spin. Modi handed education and culture to the dogmatic RSS, as a reward for its support in the campaign. The movement is steadily asserting its power over the prime minister, says the historian Ramachandra Guha. All in all, the transition from “campaign Modi to governance Modi” has not been a smooth one. If anything, the rhetoric of intolerance appears to have been ratcheted up, and in some cases gone well beyond mere words, erupting in violent attacks on minorities. For example, BJP MP Yogi Adityanath spearheaded a “ghar wapsi” (homecoming) campaign to convert Muslims and Christians by force to Hinduism. Although politicians like Adityanath are tarnishing Modi’s international reputation, it is difficult for him to restrain them, since their platform of religious nationalism got him elected. “It’s not a remote control thing that you can switch on and off as you please,” notes the journalist Varghese K. George.

Modi’s other key platform—economic revitalization—looked shaky. With little to show for its grandiose election claims, the BJP failed in its first major electoral tests after coming to power: it was beaten badly in elections in Delhi and Bihar in 2015. In the absence of strong economic results, identity politics may continue to be the cheapest way to win support. Midway through his first term, the prime minister had yet to go out of his way to reassure minorities that their status was secure.

The main restraint on the Hindutva agenda may be the country’s sheer ungovernability—an obstacle that has thwarted Indian leaders’ most progressive intentions, and may do the same to Modi’s Hindu nationalism. Everything, from India’s federal system to its irrepressible argumentative tradition, conspires against totalizing visions. The courts and the quasi-judicial commissions provide additional structural safeguards, says the constitutional lawyer Bhairav Acharya. In addition, other state imperatives, especially national security, may kick in. After a spate of widely publicized attacks on Christians, including the brutal rape of an elderly nun, the former navy chief Sushil Kumar made a telling intervention: India could not afford to pollute its secular environment to such an extent that it compromised its multiethnic armed forces. “The armed forces have always been considered in India as the strongest pillar of our society, and the reason is simply that we are a secular armed force,” he said. “Now to allow such a virus to percolate into the armed forces is a very dangerous thing.”

Most of the prime minister’s rhetoric has focused on the economy and foreign affairs. At the same time, Modi continues to say and do enough to encourage his core constituency on the Hindu Right that the dream of Hindutva is still alive. His divisive rhetoric is striking for its economy. He does not have to say much. Thanks to decades of Hindutva hate propaganda, the ongoing campaign to rewrite Indian history, and the pogroms of Muzaffarnagar and Gujarat, Modi’s adulatory audience can fill in any blanks he leaves with readily accessible mental flashcards. In one of his first parliamentary speeches as prime minister, Modi referred, in passing, to the need to shed “1,200 years of slave mentality.” His audience required no further elaboration. They knew that negating twelve centuries of history meant transcending not just British colonialism but also India’s Muslim heritage. Here was Modi’s vision of India’s tryst with destiny: a glorious Hindu civilization, foreign invasions, minorities who demand more and more, and a strong leader prepared to teach those invaders a lesson.

This an excerpt from Hate Spin: The Manufacture of Religious Offense and its Threat to Democracy by Cherian George, published by The MIT Press (2016).

Footnotes have been removed.